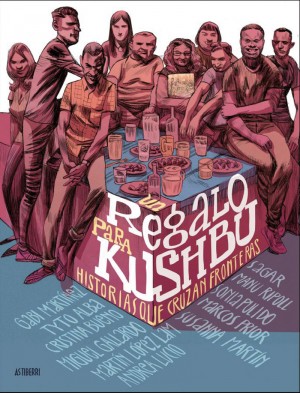

Un regalo para Kushbu [A Gift for Kushbu]

Un regalo para Kushbu [A Gift for Kushbu]

Various authors

Jointly published by Astiberri Ediciones and Ajuntament de Barcelona

Barcelona, 2017

131 pages

For some time now, non-fiction not only fills the pages of well-known writers like Capote, Mailer, Carrère or Caparrós, but also the illustrated pages of graphic novels, which have allowed the rigorous and socially committed binomium between journalism and comics. Un regalo para Kushbu is the closest example we have in time and space of this hybridisation of genres.

One of the chief characteristics of the Mediterranean city of Barcelona is its cosmopolitan, integrating and multicultural nature, which strives to keep a balance between receiving tourists and welcoming migrants, between leisure and economic activity, on one hand, and solidarity and social responsibility, on the other. The richness of diversity, though, has a built-in challenge that has to be faced in all its complexity: how to promote equal rights and opportunities for those people arriving in our city in search of a brighter future and who, just because of their origin or physical appearance, do so with the label of a stigma on their shoulders.

All this paternalist objectification does though is to reinforce the first stone in the exclusion mechanism: prejudice. In this aspect, social and occupational inclusion instruments are among the best assets we have to offer them, and fortunately not only do we have a lot of them, they also work efficiently thanks to teamwork and collaboration on the part of public entities and bodies.

One of them is the Mescladís, a foundation that works with individuals and associations linked to activism, education, art and culture. From its meeting-place, the Espai Mescladís, it runs a project that generates its own resources through various initiatives in social and solidarity economy, training and mentoring in the employment market for people with special difficulties for getting jobs.

Last December this project grew a bit more thanks to the publication of an unusual graphic novel: Un regalo para Kushbu. Historias que cruzan fronteras [‘A Gift for Kushbu. Stories that Cross Borders’] produced by Mescladís and the Al-liquindoi Association, jointly published by Astiberri Ediciones and Barcelona City Hall. A book that has brought together nine lives through nine anonymous stories, so much like those of so many people but so little listened to.

This project reveals the collective awareness we all have the duty to take on board and share, because their stories could be ours, because not so many years ago they were our grandparents’ stories. Don’t forget the past and don’t ignore the present; memory must not be capricious. ‘I’m a man, nothing human is irrelevant for me’, said Terenci Moix. Un regalo para Kushbu reminds us precisely of that: the protagonists of these stories are real people, forced to flee their country, arriving in an unknown place in search of an easier, fairer, more human life.

Putting a face to people seeking refuge

What is special about this graphic novel that crosses borders, both figuratively and literally, is that it’s been drawn by the ten hands of the illustrators Tyto Alba, Cristina Bueno, Sagar Forniés, Miguel Gallardo, Martín López Lam, Andrea Lucio, Susanna Martín, Marcos Prior, Sonia Pulido and Manu Ripoll. It also has photographs by Joan Tomás and a script by the writer Gabi Martínez. The comic, which arose from the Diálogos Invisibles (Invisible Dialogues) project by Martín Habiague, Jessica Murray and Joan Tomás (presented at Barcelona DOCfield), describes the adventures of these nine people and tells us about their troubles and hopes and of their personal struggle against abuse and discrimination, persecution and war.

In an age conditioned by mass migration as well as generalised mass silences from many of the countries that pride themselves on their democracy from behind their borders, Un regalo para Kushbu becomes a testimony to the support and solidarity its protagonists have found to confront exclusion: Farida, from Afghanistan; Raju, from India; Basanta and Kushbu, from Nepal; Dilora, from Uzbekistan; Ilyas, from Morocco; Bubakar, from Niger; Soli, from Nigeria; and Camilo, from Colombia. On the back cover of the book, Elvira Lindo says ‘we must put faces and names to those seeking refuge’ simply because ‘it’s a moral obligation’. ‘We want to welcome’ must not be just a cry, it must be a reality.

In an age conditioned by mass migration as well as generalised mass silences from many of the countries that pride themselves on their democracy from behind their borders, Un regalo para Kushbu becomes a testimony to the support and solidarity its protagonists have found to confront exclusion: Farida, from Afghanistan; Raju, from India; Basanta and Kushbu, from Nepal; Dilora, from Uzbekistan; Ilyas, from Morocco; Bubakar, from Niger; Soli, from Nigeria; and Camilo, from Colombia. On the back cover of the book, Elvira Lindo says ‘we must put faces and names to those seeking refuge’ simply because ‘it’s a moral obligation’. ‘We want to welcome’ must not be just a cry, it must be a reality.

Un regalo para Kushbu is another example of the consolidated rise of the graphic novel as a form of literary expression during this century, especially when it comes to stories with a high level of social protest based on real facts. With the indisputable iconic reference to Maus, the story in pictures and the exercise of the historical memory that goes with it have become another way of representing journalistic non-fiction. Atisberri, along with Norma, Sinsentido and Planeta Cómic, is one of the leading publishers of works in this genre, which stands out for the work of Joe Sacco, Guy Delisle, Marjane Satrapi, Rutu Modan and the Valencian Paco Roca. Un regalo para Kushbu follows the line of Los vagabundos de la chatarra (2015), the comic written by Jorge Carrión and illustrated by Sagar Forniés with which we can walk the streets of the Barcelona of the documentary film Ciutat morta [Dead City] through graphic journalism.

But Barcelona isn’t just the city in Ciutat morta. It’s also a city of refuge which for so many years has shown its democratic and integrating virtues. The social and cultural commitment of Mescladís continues to make sense of a perception which, in spite of all the injustices, is still as alive as ever.