The City Protocol Society is under way. After just over one year of preparation, the international consortium that promotes the so-called City Protocol – a set of agreements and standards that can be shared all over the world for the development of smart cities – was formally established in California in October 2013. Barcelona is playing a leading role in this process.

San Ramon is a small city about 40 kilometres east of San Francisco (California, USA) and about 50 north of the heart of Silicon Valley. It is not as well known as Palo Alto, Cupertino, San Jose or Menlo Park, but it might become so in the medium term because San Ramon is the official headquarters of the City Protocol Society. This non-profit organisation promotes the definition and adoption of global standards for the gradual transformation of cities into what are internationally known as smart cities.

The Californian city of San Ramon hosts the official headquarters of the City Protocol Society. However a large part of the project’s soul resides in Barcelona, the capital that is also home to the secretariat of this as yet young institution (located in the Recinte Modernista de Sant Pau).

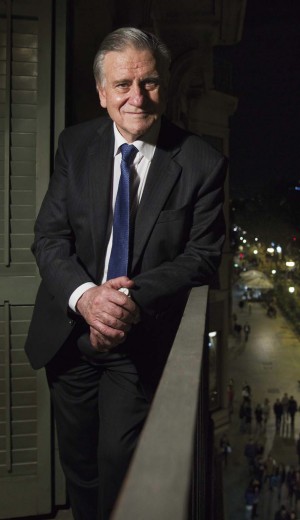

“The project was born of a discussion on the future of smart cities and the need to share experiences and solutions,” recalls Manel Sanromà, Manager of the Municipal Institute of IT of the Barcelona City Council and, since last October, Chair of the City Protocol Society. “Companies design technology to provide solutions to the problems different cities face, but since all cities have similar problems, the result is that similar solutions are made without a great degree of collaboration between cities, and they lack recommendations or standards that would make it possible to access these solutions in a more efficient and flexible manner,” explains Sanromà.

This reflection on the reality of smart cities uncovered the need to set up a forum where cities, businesses, academia, research centres and civil society could help analyse problems and propose universal recommendations or standards.

Organising a process of this kind – with thousands of cities, companies and researchers working in parallel – does not seem too easy, but the internet offers a possible answer. “The miracle of the internet is that different companies, manufacturers and users end up working to the same standards, de facto standards that have not been imposed but have been created from the bottom up,” explains Manel Sanromà, who is highly conversant with the Internet Protocol and Internet Society creation processes.

The reality of growing smart cities and the experience accumulated with the internet inspired the creation of a City Protocol, a process that would be led by the City Protocol Society. The proposal was conceived at a meeting held in Barcelona in the summer of 2012, involving more than 200 experts and representatives of 33 cities, 15 universities and some 50 companies and institutions.

After one year of preparation and work, the City Protocol Society was formally established last October with the support of some 30 cities, companies and universities or research centres.

Manel Sanromà points out that apart from the founding act, “the key part of the process begins now, with the creation of task forces to address specific issues in areas such as energy, mobility, the environment and technology. These City Protocol task forces will begin to issue recommendations and agreements and perhaps, in the future, common standards for city development.”

A key part of this process is the definition of a participation-based procedure leading to the adoption of agreements and protocols on a global scale. The City Protocol can affect many aspects or levels of the so-called smart cities, but certainly it is easier to define standards in those areas related to technology. “Standardising governance is a task that is expected to be difficult, but to do so we must have a standardised system for publishing data about cities. This can be done through open data, for example. It is possible to consider defining global standards,” says the Manager of the Municipal Institute of IT.

In topics related to the present and also further in the future, such as the use of electric vehicles in cities, the City Protocol could be used to establish standards regarding system characteristics and battery-charging points. “We would undoubtedly find many practical examples, but the key is for the City Protocol to be applicable to all areas that we see as forming part of cities’ anatomy,” explains Sanromà. “In some cases agreements will be reached, whereas in others we may only be able to issue recommendations, although under no circumstances should we impose limitations on ourselves, because the scope is very broad.”

Now that the City Protocol process is up and running, and the City Protocol Society has been legally constituted, the immediate objective is “to spread the idea and the movement in order to reach 100 member organisations in 2014, including several dozens of cities”, continues Sanromà. Parallel to these efforts, the City Protocol Society will continue to work on organising the Task Force, or groups of people from all sectors working as volunteers to discuss problems and prepare proposals and protocols.

What is the City Protocol?

The City Protocol is a system for the rationalisation of city transformation based on dialogue and research on information, recommendations and standards that can be shared by all urban communities worldwide. The City Protocol Society (CPS) is an international non-profit organisation comprised of cities, businesses, academic institutions and other social organisations whose goal aim is to lead the creation of the City Protocol.

The City Protocol aims to work in all areas that affect the life and development of cities and their inhabitants. The task forces whose mission is to prepare agreements and standards (City Protocol Task Force) are organised into eight general areas: environment (air, land, water), infrastructures (information, water, energy), buildings (homes, construction), public spaces (streets, squares, parks), functions (living, work, health), citizens (people, organisations), information flow (legislation, economics, metabolisms) and actions (resilience, self-sufficiency, habitability, safety and innovation).

Cities, organisations and companies

“Barcelona promoted the idea and is determined to continue to bolster the project with maximum support from Mayor Xavier Trias, although there are many other cities and organisations that are working hard in this process, one that has just begun and which we must spread globally,” asserts the Chair of the City Protocol Society.

The constituent meeting of the new society was held on 31 October 2013 in Barcelona with the appointment of an initial board comprised of representatives from the cities of Amsterdam, Barcelona and Quito, the Cisco and GDF Suez companies, the Computation Institute of the University of Chicago and the New York Academy of Sciences. Other members include the cities of Dublin, Genoa and Moscow, as well as companies and organisations such as Cast Info, Cityzenith, Microsoft, OptiCits Ingenieria Urbana, Schneider Electric (formally Telvent), Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC) and the Rovira i Virgili University (URV).