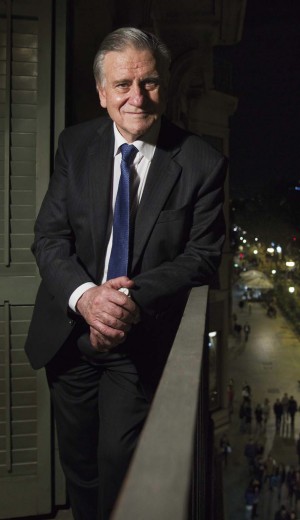

“Doctors have a commitment to society that we cannot forget,” says Dr Valentí Fuster, director of the Cardiovascular Institute at the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York and the Carlos III National Cardiovascular Research Centre in Madrid. This social vocation has led this doctor from Barcelona – one of the world’s leading cardiology experts – to work untiringly as a disseminator and educator.

Allow me to begin with an anecdote: some sources say that you were born in Cardona…

Yes, it’s one of those biographical errors you can find on the Internet. As an adopted son of Cardona, I am very committed to it, and my wife was born there, but I am actually from Barcelona.

Your family relationship with Barcelona could hardly be closer: your father, Dr Joaquim Fuster i Pomar, was director of psychiatry at the Hospital de Sant Pau, and both of your grandfathers were doctors; one of them, Valentí Carulla i Margenat, was rector of the University of Barcelona from 1913 to 1923…

I never met him personally, but I researched him thoroughly and wrote my maternal grandfather’s biography. Valentí Carulla was a very interesting man anddeeply committed to education. It was he who achieved access to school for everyone in Catalonia, regardless of the family’s economic situation. My father was the director of psychiatry at Sant Pau and later managed the Sant Andreu mental hospital. He had his private practice very close to home. My paternal grandfather was also a doctor, practising in Mallorca. My older brother is a neurophysiologist and works in Los Angeles.

What family memories do you have of the Barcelona of your parents’ era?

My father was an intellectual, and I have a very clear memory of the meetings he held every Sunday with the group he called “the gang”. I remember my mother’s social involvement very particularly. My father was from Mallorca, and he came to live in Barcelona; the family settled in Pedralbes, where, as I said before, he had his practice. He was a psychiatrist and gave me the freedom I needed to develop as a person, for which I will be eternally grateful to him. My mother instilled a strong social concern in me.

Besides the family tradition, when did you decide you wanted to become a doctor?

I did my higher secondary education at the Jesuit school in Barcelona and wanted to study agriculture, because I have always liked nature and research related to the land. However, at that time there was no agricultural university course in Barcelona and it was hard to move away from the family environment. In the end, I chose medicine, thanks also to the influence of Professor Pere Farreras i Valentí, one of the most influential doctors in this country and abroad.

Your older brother chose the same medical speciality as your father. Why did you go for cardiology?

Dr Farreras had a heart attack, when he was 42, if my memory serves me well. He was my tutor or mentor, and he told me that cardiology was a field he had not mastered as well as other areas, and that I could devote myself to it. This advice was absolutely transcendental in my career.

What do you remember about the Barcelona of the 1960s, when you studied medicine at the University of Barcelona, or the Central University, as it was known then?

The most positive thing I remember is the intellectual relationship with some colleagues, such as the philosopher Eugenio Trías Sagnier, the architect Manuel de Solà-Morales and Agustí Arana. We held meetings like those of my father and his “gang”.

And your brief spell at the Hospital Clínic, at the end of your training phase in Catalonia?

There were some very good professors – three or four – but others just used their notes. I preferred books, for example, in English, and to my mind notes lacked intellectual ambition. I had some professors who were simply incapable of motivating their students. That was one of the reasons why I left Spain; I needed motivation. Dr Farreras helped me to get to the United Kingdom first, where medicine was more straightforward and less technical. Then I came back and set my sights on the United States, and there I stayed…

Was it difficult to make it in the States?

They made things very easy for me. I got some very good letters of recommendation from the United Kingdom and was accepted at the Mayo Clinic. I had to start from scratch, but it was worth it.

What is – or what was – so different between the research conducted in North America and in other parts of the world, not to mention Spain?

Motivation. In the United States, people who work are given all kinds of support from day one. But it is a very demanding country: if you work there they will help you, although the level of demand becomes progressively higher…

What are the current challenges in the cardiology field?

The first major challenge is to go from treating diseases to promoting health. Prevention is crucial; developed countries spend vast amounts of money treating preventable diseases. Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death in the world, since almost 40% of deaths are caused by these types of problems. We are facing an epidemic because of problems from being overweight, bad eating habits, smoking, lack of physical exercise and so forth. Prevention is of the essence, since at this rate it will be impossible to cope with the expenditure incurred in the treatment of disease.

You mentioned other medical challenges…

We need to make progress and relate studies on the heart and brain. A lot of progress is also being made in imaging technologies, genetics and tissue regeneration. Is it also very important that we know how to apply our knowledge to patients quickly. Finally, and more generally, we have to fulfil our social responsibility: doctors have a commitment to society that we cannot forget.

Allow me to remind you of one of society’s great dreams: when will we be able to use stem cells to regenerate a heart damaged by a heart attack?

Many teams all over the world are working with stem cells. The National Cardiovascular Research Centre in Madrid has several lines open in this field. This work will eventually yield positive results, but although part of society and many journalists always enquire about these types of solutions, I would like to emphasise the most effective way forward that we have is within reach: healthier lifestyles and habits.

You attach particular importance to pre-school education, to the habits of younger children…

The things a child learns at the age of four or five are transcendental for their adult life. Learning healthy eating habits and how to look after their body from a young age is something that will stay with them for many years.

Tell us how the education campaign on healthy habits for children through the Sesame Street television series came about.

At an expert meeting addressing the great problem of obesity in the United States, I voiced a critical opinion on the food industry. One of the managers from the Sesame Street production company approached me and we decided to work together. Now we are working on health education programmes with children from all over the world.

Has the experience also been applied to Spain?

The SHE Foundation and Sesame Workshop, with the support of the Daniel and Nina Carasso Foundation, reached an agreement to produce a new Sesame StreetTV series in Spain. Last year, 26 episodes were broadcast, targeting children aged from three to six, in which nutrition, physical activity, knowledge of the body and heart and social and emotional well-being take centre stage. All the contents are prepared by a team of international and local experts in order to instil healthy and lifelong habits in youngsters. It is a series with great potential for expansion.

This gave rise to the Foundation for Science, Health and Education project. Or are they different developments?

We have many parallel programmes and actions in health education matters for people of different ages, and we saw the need to focus all this activity in a foundation that would be dedicated to working on the basis of scientific research with a view to promoting health through communication and education. The collaboration with Sesame Streetis part of the SHE Foundation’s projects.

And how does your foundation’s other flagship project, dedicated to integral health, work?

The SHE Foundation has implemented the SI! (Salut Integral!) [Integral Health!] programme, in which more than 11,000 boys and girls from 61 schools are currently participating. The idea is to go beyond obesity prevention, treating health in an all-encompassing way, through four basic and interrelated components: learning healthy eating habits; physical activity; knowing how our body works – particularly the heart; and managing emotions and promoting social responsibility as a protection factor against addictions and the consumption of substances such as tobacco and drugs.

Your recipe for cardiovascular health is easy to recite and — for some people — hard to follow. Could you remind us of the basic ingredients of this recipe?

Prevention is crucial. However, in general, if we want to know how to lead a healthier life, I would highlight three or four specific things: do physical exercise, avoid becoming overweight or obese, maintain a healthy blood pressure and refrain from smoking. Do you think that people don’t know these things? Now it is important to put them into practice.

We used the word “recipe” previously, and you have written informative books, accompanied by experts and figures from many other fields, one of them being the prestigious chef Ferran Adrià. What do you remember about this particular collaboration?

Ferran Adrià has made outstanding contributions to modern cuisine, and in recent years he has also evolved towards other fields, such as healthier and more accessible cooking. The collaboration in the book may seem paradoxical, because I, a researcher, talk about cooking, whereas Ferran Adrià, a chef, explores the world of research. We both share a need, or a moral obligation, to go out there and explain important things, such as the easiest ways to prevent a heart attack or the basics of good nutrition. The journalist Josep Corbella managed to convey all this in the book.

You manage research centres on both sides of the Atlantic and run top-level research lines all over the world, so how do you find the time to write books and spread science?

I do it to contribute to the society that has given me so much. It is a gesture of responsibility. In the case of books, I have written with outstanding people such as Ferran Adrià, who we just mentioned, the psychiatrist Luis Rojas Marcos in Corazón y mente [Heart and Mind], and the writer and economist Jose Luis Sampedro in La ciencia y la vida [Science and Life]. I wrote the first book of this kind, La ciència de la salut [The Science of Health], in collaboration with the journalist Josep Corbella. In all cases I would like to emphasise that I have met highly motivated people strongly committed to society, although the fields they work in and their ways of thinking are different to my own.

In any event, defend your field of work a little for us. Should society give scientific research greater recognition and invest in it more?

It is evident that society does not properly acknowledge the work of researchers and the importance of science. Our future depends on important matters such as education and science, and citizens therefore must have a greater scientific culture, and research should be given major importance. In this regard, the media and journalists have an important role to play. You have to tell society that science fuels a country’s future.

How do you see the future of scientific research in Spain in general and in Catalonia in particular?

I am concerned. We have been working for years to push science forward and now there are great challenges and problems to overcome. In any case I hope that the positive line will continue. The National Cardiovascular Research Centre, sited in Madrid, but which is spreading all over Spain and abroad, works on many projects that lead to significant scientific progress and we aim to continue along this path. Catalonia is one of the European regions with top-quality researchers who engage in very good scientific research. Major cutbacks in the scientific research budget will only jeopardise the future.

Have you ever missed working in medicine in Barcelona full-time?

I have a very close relationship with Barcelona. I work on a great deal of projects related to research and health in the city and am delighted to be able to continue to do so.

2012 National Culture Award

In Catalonia, Dr Valentí Fuster was awarded the 2012 National Culture Award, in the Thought and Scientific Culture category, for “his contributions to biomedicine in the cardiovascular field and untiring commitment to promoting social awareness in order to improve health by means of disease prevention,” according to the awards panel, which is given by the National Council for Culture and the Arts (CoNCA).

Born in Barcelona on 20 January, 1943, Fuster holds a degree in medicine from the University of Barcelona and honorary degrees from some 30 universities all over the world. He began his career as a cardiologist in Edinburgh (United Kingdom) and settled in the United States in 1972. He lectured in medicine and cardiovascular diseases at the Mayo Medical School in Minnesota and at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, and was Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston from 1991 to 1994.

He has authored almost a thousand scientific articles and two of the most prestigious books at international level on clinical cardiology and research, and his work has had a great impact in helping to improve the treatment of patients with cardiac illnesses. His research into the origin of cardiovascular accidents has earned him the most major awards from four of the world’s four major cardiology organisations, including the 2012 American Heart Association (AHA) Research Achievement Award. In 1996 he received the Prince of Asturias Research Award. J.E.