A look at some initiatives designed to improve the urban landscape with a new vision of our cultural heritage, through proposals from the International Master’s Degree in Landscape Intervention and Heritage Management.

The way we understand our landscapes, study them and manage them has changed considerably over the past decade. Starting in 2000, the European Landscape Convention encouraged states to promote public policies on landscape management. Here, this started to be applied in 2005 with the creation of the Landscape Observatory of Catalonia. This organization depends on the Government of Catalonia and, unfortunately, is only an advisory body; its proposals are not legally binding. The Landscape Observatory and other organizations such as the geography departments of the Autonomous University of Barcelona and the University of Girona work on landscape as the relationship between nature and culture.

One of the most interesting changes in how landscapes are managed involves the analysis and management of ordinary landscapes, those that are not considered exceptional by the administrations and that, as a result, are not protected. Ordinary landscapes include the places most of us live. The preamble of the aforementioned European Convention states that we all have the right to landscape, which is essential to our quality of life.

Most landscapes aren’t exceptional, at least in the classical sense of having a unique, universal value. However, they all create a sense of place and contain a series of values. In some places, these values have been lost; in others they’ve been blurred, and we need to study them to identify them once again. Our landscapes also need to be well-managed so we can recuperate these values and keep our landscapes from being simplified, becoming thematic or turning into museums and losing their identity.

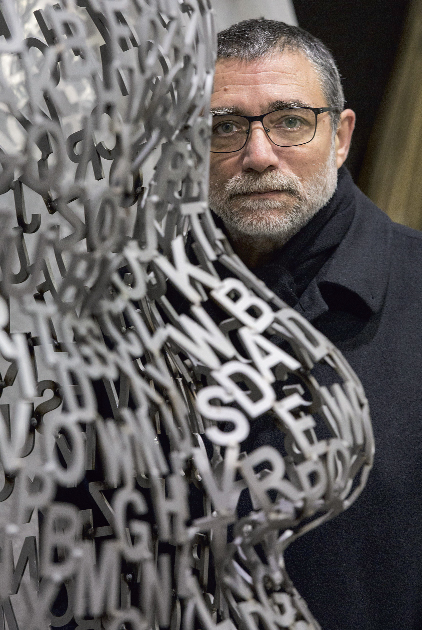

This vision drives the work of geographer Francesc Muñoz, director of the International Master’s Degree on Landscape Intervention and Heritage Management promoted by the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and the Museum of the History of Barcelona (MUHBA). According to Muñoz, “in ordinary landscapes, there’s nothing to catalogue. It isn’t about looking for extraordinary elements, it’s about creating a network and associations for both culture and nature, by recovering the collective values contained in these landscapes. It’s about empowering the public on a local level.”

Through their international workshops, which involve multidisciplinary teams from different European Universities that are part of UNISCAPE (the European Network of Universities for the Implementation of the European Landscape Convention), the master’s program has provided a series of interesting and innovative proposals to recover the value of our heritage in a series of locations in Barcelona, while also considering a new use for urban space that is beneficial both to the people that live there and to the city in general.

According to Francesc Muñoz, “faced with the homogenizing tendency affecting European cities, our workshops try to reflect and offer alternative models that emphasize urban differences and understand the value of different spaces, in terms of their culture and their peculiarities.” We asked him to provide a selection of workshops on different parts of the city of Barcelona as examples of these reflections on how to manage and use ordinary landscapes.

Block courtyards in the Eixample

The gardens of Ermessenda de Carcassona in the block courtyard at Carrer del Comte d’Urgell 145.

Photo: Pepe Navarro

The forty-eight block courtyards in the Eixample, which include almost a hundred thousand square metres of space reclaimed in recent years, are an opportunity to rethink the qualities of public spaces in 21st-century cities. The workshop considered proposals to establish relationships between city blocks and reclaimed interior spaces, using digital technologies or considering new designs, taking into account issues like climate change or citizen environmental awareness.

School routes in Gràcia

This workshop suggested introducing children to the process of diagnosing and planning urban public spaces to guarantee their empowerment as active citizens and their capacity to offer ideas and proposals. The paths taken by families on their way home from school in the afternoons were digitally mapped to detect where children spend the most time and the places they most often visit during the week. Then, by working together with children, their visual and landscape preferences were established. From 2013 to 2015, four new school paths were set up in Gràcia, while others are currently being considered or redesigned.

Shared landscapes: the Pere IV axis

The intersection of Pere IV and Badajoz, in El Poblenou, where an attempt is being made to promote ordinary urban heritage.

Photo: Vicente Zambrano

The international workshop considered the need to work with ordinary urban heritage and the opportunities it can provide. In the case of El Poblenou, certain landscape elements such as alleys, party walls, leftover elements from former factories or even fire escapes make up a whole new cartography, partly latent and partly hidden, involving values of identity. It’s a real “catalogue of everyday heritage” that intervention in the urban landscape can clearly activate, making every-day heritage into a new and promising tool for urban planning in the context of the current city.

Water-based heritage

When recuperating the former industrial heritage of the city, lesser elements are often forgotten, such as those having to do with water: constructions to store and contain it, lavoirs, fountains… Today, these constitute a cultural heritage (tangible or intangible, depending on the case) which can still be taken advantage of. In the case of the neighbourhoods of Trinitat Vella with the Casa de l’Aigua (Water House) and Sant Andreu with the Rec Comtal canal, the workshops proposed urban itineraries to reconnect citizens with this cultural heritage, as attractive spaces that represent Barcelona’s industrial identity and memory. Along these lines, organizations like the Centre d’Estudis Ignasi Iglésias, among others, organize activities to promote knowledge of the Rec Comtal, such as exhibits and itineraries.

The waterfront

Starting in the 1980s, almost all of Europe’s old ports were transformed into new spaces for recreation and entertainment, and most are quite similar. In the case of Barcelona’s waterfront, the urban experience with water is minimal, even though water takes up quite a large area.

For the Moll de la Fusta, the workshop came up with specific initiatives and redesign projects for the waterfront that would bring citizens closer to the watery landscape while also establishing new relationships among different spaces in the port sector, which could help to return citizens’ “right to landscape” as far as water is concerned.

Large industrial spaces: Besòs power plant

The thermal power plant in Sant Adrià de Besòs closed in the summer of 2010. Since then, five international workshops have been organized with the goal of preparing projects to recycle it, contemplating its value both in terms of landscape and heritage. A group of ten European and American universities, represented by some two hundred students and professors, have worked to maintain this facility as a landscape monument with a clear metropolitan character.

This coming summer, a sixth workshop will be organized to summarize all the work done so far. The common thread in these different proposals lies in considering the value of the power plant in terms of landscape and heritage, as a catalyser for an entirely new landscape on the Besòs coast, capable of combining different types of economic, social, cultural and heritage-based uses; an active cluster of new activities and relationships between areas, inspired by the aesthetic and landscape-based value of a privileged metropolitan icon.