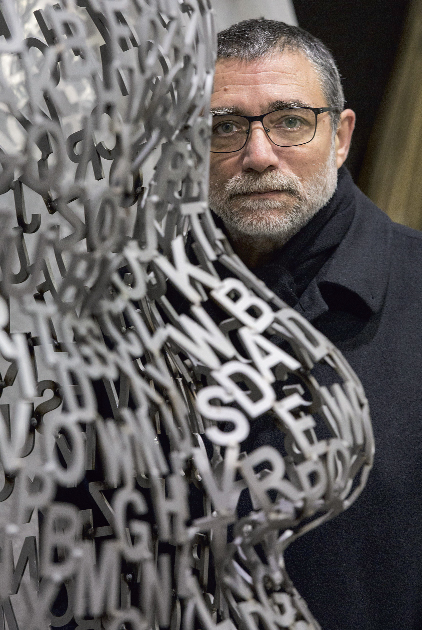

Sculptor Jaume Plensa has just won the Barcelona City Prize in the ‘International Impact’ category. He is enjoying a new millennium of vibrant creativity and increasing recognition. From his studio, Plensa shares his thoughts on the humanisation of art and the role of his art in public spaces.

The studio of sculptor Jaume Plensa occupies a warehouse in an industrial estate in Sant Feliu de Llobregat. A bare, icy space with no remarkable features, it initially seemed to Plensa a place of exile. But now he’s made it his own: “It’s a non-place, situated between a rubbish tip, which I see as a storage facility for memories, and the cemetery, which is the future. This studio is virgin territory. That’s why I like it. I’ve been here for twenty-three years now.” As an internationally renowned artist with works on display in dozens of cities across the world, Jaume Plensa could have settled in Berlin, Brussels, Paris, New York or Chicago, but his workshop lies right next to Barcelona, to the great advantage of our city, where he was born in 1955.

Whilst it was his work with cast iron that brought him international prestige, Plensa is an artist that has also experimented with sound and light. He has been working with other materials for fifteen years now, frequently with the human body as his focus. His public sculptures are very recognisable, like the large heads of adolescent girls with their eyes closed, bodies made out of words or letters of the alphabet, or figures in contemplative poses sitting on top of masts or with their arms around trees. Inside the studio, where a seven-strong team works, lie some of these pieces. Some of them are about to depart for Santa Fe while other, smaller ones are studies for some pieces that have been exhibited at Augsburg. In one corner two craftsmen give form to the sculpture that Plensa will be unveiling at the church of San Giorgio Maggiore during the Venice Biennale in May.

Plensa argues that beauty is one of the essential elements of his work. He is particularly well known for his sculptures in public spaces, a genre that still remains virgin territory (as it is misunderstood and often mediocre). A contemplative man, conscious of the role that his work must fulfil and of the positive impact that it must have on the community in which it is located, he becomes almost transcendental when he speaks of poetry as a revolutionary driver for creativity, and of silence in a world that is too noisy, where it is difficult to find oneself.

This desire to convey beauty through your work has a great deal of kindness in it. But do you not find the word “beauty” an uncomfortable one, since beauty is really in the eye of the beholder?

I don’t think that beauty is uncomfortable. Maybe people feel uncomfortable about beauty, because it is an instrument of extraordinary political force; because it makes no concessions. Beauty is not something one can negotiate with. It just is. That carries a lot of weight in the world of art because it is one of the major things that an artist must give throughout his or her creative career. Of course you can ask, what is beauty? I believe beauty is the vast place where you, he and I, everyone, can find ourselves. It’s very closely linked with memory. Once, when I was having a few drinks in Santiago de Compostela with José Ángel Valente, who is an outstanding poet, he said: “Jaume, never forget that memory is more vast than our recollections”. Beauty is like that. I can think of no more important purpose than to create beauty. One might make mistakes, one might get it right (that’s for others to say) but this desire is primary.

Do you understand the reason for this discomfort?

Currently, at this turn of the century, there’s a kind of blurring of the meaning of words. When one talks of morals, ethics, beauty and poetry, these words appear to have been misinterpreted, because they’re seen as old-fashioned, anachronistic, romantic. I don’t agree with that at all. We need to give the original content and meaning back to these words. Beauty, or the search for beauty, is an intrinsic part of the human condition. It’s also true that sometimes we are more interested in the notion of the grotesque or the ugly, but that’s alright because, by contrast, we’re also talking about beauty.

You were born to a family in which literature and music was very important. You went through the Llotja Advanced School of Art and Design and spent a couple of years in Fine Arts, soon after you left for Berlin, then Brussels and Paris and became a man on the move. Yet your first exhibition was held at Espai 13 in the Miró Foundation in Barcelona. Did that have any impact on you?

It was important. Miró and Calder were my heroes when I was little. They gave me an amazing outlook, and I’m glad to see that the world is beginning to understand Miró a little better. There has been a kind of rediscovery of Miró, because people had misunderstood him. Espai 13 was a great experience because through that I also met Joan Brossa and Antoni Tàpies. Tàpies and I became great friends. He was someone I didn’t just admire but venerated, because to me he was like a Renaissance artist; a very well-rounded man. Around that time I also met Chillida.

How did that go?

I managed to exhibit some forged metal pieces at the Madrid ARCO fair through a gallery in Vic called La Tralla. I saw Chillida from afar as he was walking towards the stand. He stood in front of the works and asked: “Who’s the artist?” When he shook my hand, I was shaking with nerves. And he said: “Jaume, keep up that purity”. I thought to myself that if Chillida liked it, I’d have to radically change my work, because I was sure it was bad. It was obviously a way of killing off one’s father. So I completely changed my work.

This talk of Chillida reminds me of the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA), because of the piece situated outside the museum, I suppose. Will the MACBA put on an exhibition of your work?

I’ve never gone looking for anything in my life, I’ve always just found opportunities along the way. I’ve always followed a rather individual and solitary path.

You have works or you’ve exhibited in Berlin, Chicago, New York, Paris, Tokyo, Venice, Frankfurt, London and dozens of other cities. Your works are recognisable wherever they are, regardless of the disparate settings they are in. This career that you’ve made for yourself by creating public art has also made you something of an expert in cities.

Firstly I should say that art is always public. So when I hear the phrase “public art”, I don’t get it. I understand art in public spaces. I’ve worked with opera and I’ve always thought of the theatre as a public space. And museums are also public spaces. A gallery is a private public space. Having said that, working in a community’s public space (a street, a square, a park) is really interesting because it is a wilderness, it has no context. When you work in these spaces, there is nothing to state that the piece is a work of art. It has to fend for itself. But when I exhibit at a gallery or museum, the visitors are predisposed to finding something one can call art. We are living through a very interesting period because what we might call monuments (or commemorations) are made by architects.

Does the prevalence of architecture affect the way art is made for public spaces?

Today, a city’s landmarks are architectural; its landmarks are its buildings, and this has given artists a fantastic opportunity to express other things. We don’t need to commemorate anymore, that’s what architects do. And one of the things this allows artists to do is to give form to the scent of a community. In the perfumery business there are certain plants that are used to set the fragrance so the scent doesn’t disappear. I believe that art in a public space is that humble little plant that helps to set the fragrance of a community, to give it an identity and a value. It delves into a world that is already there and completes it or helps it to regenerate, breathing new life into it.

How do you get close to a city?

When I’m invited to work for a city’s public space, I try to understand the everyday life of the community. Let me explain using an example: I did a project in Calgary, in front of a new building designed by Norman Foster – it was a curved building, creating a square in the city centre. A group of art advisers thought it a good idea to ask me for a piece that would give the place a new spirit. I remember the meetings we had in London, where everyone kept warning me about scale, because of the size of Foster’s building. But I wasn’t in the least bit interested in looking at the relationship with the scale of the building. I wanted a relationship with people. My piece, which is twelve metres tall in front of a building that is one hundred fifty metres tall, forms a bridge that somehow protects the little ants that we have become around these gigantic buildings that crush us. Works of art are like a little David facing a gigantic Goliath. Art creates the link that humanises the space, because it gives scale to the human being. Art in a public space once again has a leading role to play, because of the need to give people the tools to feel like people again, because architecture has lost its essential purpose of embracing people. We should go back to a more human form of architecture.

You believe strongly in the need to create a link between art and the community. Is this one of your major contributions?

In my work, I have always wanted to connect with the community, with people. I love people, wherever they’re from. That’s why I like travelling so much. Every single one of my memories of a city is linked to the people I met there.

The Crown Fountain in Chicago is a piece of art that expresses this purpose very well.

Yes, it’s a great example of that aim to make people the protagonists, the soul. It’s these anonymous people that make a society. Society is a permanent community that is fluid, like water. That’s why that piece is so important.

The sculpture that you’ve designed for Barcelona, a project that is currently on hold, is also one that you link to water.

It’s a piece that I envisage to be not in water, but in front of water. When Mayor Trias invited me to create a piece, I did it with all my enthusiasm, knowing full well that it might never be made. Just as the sculptures designed by Miró were never made, nor the piece envisaged by Tàpies… I signed up because I’m also from Barcelona, but ours is a complex city. No one cares how much money is spent on a football player, but any money for the arts is seen as squandering, that it’s money needed for other things.

I don’t know if we’ll ever get over this problem. Our generations deserve to be able to aspire to leave some trace of our presence here, and I am stunned by the lack of courage to create landmarks that solely serve as expressions of beauty. I know that this is a time of major economic crisis, but it’s also a major crisis of values. It’s all connected. I think that it would really lift the spirits of the city to place a piece whose purpose is to just exist, to create beauty without any component of business in it.

Put like this, in such a romantic way, I think there are enough people in the city to give financial support to the project. I’ve never asked any government for anything – I strongly believe in private initiative. The piece would certainly put the city on the map, and it would be very good for the future of Barcelona.

As an expert in cities, how do you see the way Barcelona has evolved in the last few years, how its space has been occupied? Part of the population is critical of the tourism phenomenon, which it believes is not being managed well. What do you think?

Wherever you go in the world, you always incite a bit of envy when you say you’re from Barcelona. It’s a city with a peculiar balance: it’s small enough to have a human scale to it, but large enough to communicate with the rest of the world. It’s obviously not London or Paris or Madrid or New York, but if one doesn’t lose one’s sense of scale, it is an extraordinary city which, granted, is currently suffering from a bit of excess. But if you go to Vienna, it’s the same thing, Paris even more so, and Rome is just crazy. The fault I find with Barcelona, and I’ve already said this, is the lack of engagement of the public and the private sector in the city’s cultural growth. Passeig de Gràcia is now one big hypermarket, Rambla de Catalunya is not far off and all the galleries have disappeared. People don’t buy art in our galleries so what do you expect? For them to survive on nothing? Instead of going to buy art in other places, buy it here. Meanwhile, people from other cities come here to drink sangria. That is the issue, because I believe that Barcelona is rather more than a pitcher of sangria. The city’s population should be making a huge effort to revitalise the entire arts system.