La Ciutat del Born. Barcelona 1700, a publishing project led by Albert Garcia Espuche, finally dismisses the characterisation of “decadent” that has been applied to sixteenth-to-eighteenth-century Catalonia since the Catalan Renaissance. Eleven volumes with articles written by leading specialists comprehensively document everyday life in Barcelona prior to 1714.

During the last three decades of the nineteenth century

– when the Catalan Renaixença had to review the history of Catalonia, particularly with regard to rethinking the foundations of the relationship between Catalonia and Spain – one of the historiographical and methodological options chosen was the consideration that the period between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries was one of “decadence”. If one could celebrate the “rebirth” of the Catalan nation, it was obviously because the country, having recovered from the Carlist revolts and ill-fated Hispanic colonial ventures, was reacting against centuries of national decadence and darkness.

Prior to the Spanish Civil War, historians argued that, in essence, the decadence of the Catalan nation could be explained by five complementary reasons that intertwined like a web or a loop: firstly, for three hundred years the country’s demographic weakness had made it impossible for Catalonia to build up as a state; secondly, it had lost its own ruling class, Hispanicised and abducted by the Court; the literary language had also been lost to Spanish; moreover, its raison d’être was not being politically expressed in the institutions and was losing influence among the common people; finally, the fact that Catalonia was not able to trade with the Americas, having no access to the ports of the Atlantic, heralded the final cause of the collapse. This all paints a rather bleak picture of a nation which, in theory, could have found its feet again with the advent of industrialisation and which, through the Bases de Manresa (1892), could have found a way out of centuries of subjugation and political misery from inside Catalonia.

© MUHBA / Pere Vivas i Jordi Puig

Musicians and dancers at a celebration in a Barcelona garden; fragment of the ceramic frieze The Chocolate Party, dating from 1710, on display in the Barcelona Ceramics Museum.

“Decadence” was thus a word which in Catalan historiography was counterpoised to the more would-be-than-real Catalan medieval plenitude, and the expected (romantically rooted) national recovery glimpsed with the Floral Games-like Renaixença movement. Even from a philosophical point of view, decadence tied in well with the Hegelian dialectical conception and Herder’s academic historicism. In the symbolic imagery of Catalanism, the positive imperial momentum (thesis), represented by the medieval epoch, was opposed by a pro-Spain and decadent negative momentum (antithesis), of which a synthesis (or negation of negation) would be reborn. A synthesis which, it must be said, bore the element of the medieval power of the thesis without forgetting that Catalonia became a part of Spain as a consequence of the unfortunate “decadent” stage. Hence, everything made sense. Even if someone was pro-Spain by indoctrination or by conviction, arguing the alleged decadence helped to justify a pre-modern and hardly rationalist element of Catalanism.

The concept of decadence, still to be found in school textbooks on the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, is almost engrained in Catalan historiography and has been used, with somewhat ulterior motives, to describe this period and, like it or not, has also been implicitly used to criticise the weakness of a supposedly anaesthetised Catalan society. In fact, our national anthem is little more than an invitation to unite as a means of preventing that spectre from ever rearing its head again: “Catalonia triumphant, will again be rich and full”, we Catalans sing. Here there is no need to analyse the self-interested and intellectually inconsistent substance behind the construction of that concept. Let it simply be said that it is understandable that Catalanist advocates should see our history in decadent terms, particularly after the demise of the First Republic and the Spanish debacle in Cuba in 1898, when the Spanish monarchic and centralist project was rendered literally unviable due to pure anachronism.

The homeland of the romantically inclined historians, which, in the words of Gassol “was so beautiful in death/that nobody dared bury it”, needed to be rekindled, and resurrection was only possible once the country’s previous and would-be demise had been attested, which historians proceeded to do by means of the intellectual construction of a Catalan decadence vanquished once and for all. Ever since the Renaixença, as any reader of the poet Maragall well knows, here the “Grim Reaper” is Spain.

A country aware of its rights is not decadent

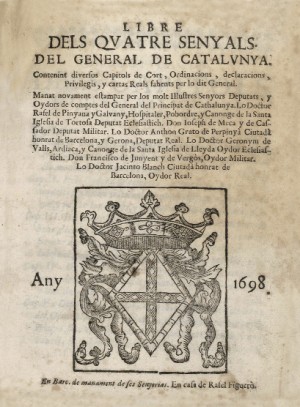

© AHCB

The Book of the Four Signals of the General of Catalonia, a compendium of the operational regulations governing the Generalitat in an edition from 1698.

This, however, was not so simple, because the facts did not quite fit into the scheme of things: How could an assumed decadence be consistent with the patriotic uprisings of 1640 and 1714 and with the country’s increased wealth, in contrast to the situation in the rest of Spain? A country that knew, as Ferrer i Ciges told the Board of Arms in 1713, that “the prince cannot pass laws and constitutions in Catalonia without the intervention, consent and approval of the Catalans, [that] the prince and his ministers can only make judgments in accordance with the constitutions of Catalonia, having listened to the parties involved, and having understood the issue” could hardly be deemed decadent. A country aware of its rights is not decadent. It was obvious that something was off and the issue was approached once again; under Franco’s rule, starting in the 1960s, a period of methodological revision of Catalan historiography commenced, which plunged the romantic models and dialectic schematism into crisis.

It was not easy to break away from the historiographical habit. It should be noted that for over a century (from 1848 to 1960), almost only one voice, that of the philosopher Francesc Pujols, argued against the historical reductionism which had condemned three hundred years into the category of “dark centuries”. Still, his Concepte general de la ciència catalana [General concept of Catalan science] was regarded as little more than a joke. Pierre Vilar was the first to assert from within academia that the eighteenth century, rather than a time of decay, had been one of economic growth. While one may argue that he got wrapped up in hasty assertions begotten of a very schematic Marxism, it cannot be denied that his contributions were significant. The work by the generation of Núria Sales, Eva Serra and Ernest Lluch attested to a radical renovation in the approach to studies on the modern era, which today we have been able to reassert through numerous contributions by young historians.

It is significant that the in-depth revision of the concept of “decadence” is one of the features that most clearly identifies the generation of historians who, between 1968 and 1982, studied at the University of Barcelona or began to teach there. In Un siglo decisivo: Barcelona y Cataluña, 1550 – 1640 [A Decisive Century: Barcelona and Catalonia, 1550 – 1640], Albert Garcia Espuche clearly demonstrates that the roots of prosperity in the seventeenth century may be found well before then, in the sixteenth century, and the rediscovery of Mediterranean history by the Annals shows the obvious parallels between Catalonia, the small towns of Italy and Dutch republicanism. Moreover, the books of Antoni Simon, who studied the documents of Simancas, pointed to the link between 1640 and 1714. Before that, the work of Catalan historians exiled in America – Marc-Aureli Vila and, particularly, Pere Voltes – demonstrated, moreover, that although the prohibition of trade between Catalonia and the Americas did exist, it had been relatively easy to get round.

Today the thesis of a decadent and Hispanicized Catalonia between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries is historiographically untenable; the publication of the Dietaris by the Catalan government shows that even among the ruling classes, political concerns were taking a different tack. Furthermore, increasing knowledge of popular culture of the period reveals the existence of a plural and diverse society with commercial activities on a worldwide scale and a national consciousness present at all times. Even historical and political chance, linked to globalisation, has, on the rebound, had a major influence on the conceptual reconsideration of the assumed decadence. The trend for post-colonial studies and the history of people without history has brought with it a new interest in the study of the strategies of the societies organised on the fringe of, or in opposition to, the state. If any society can be regarded as a republican and anti-absolutist model, it is certainly one in which the discourse of Pau Claris, collected (or reworked) by Melo, oozes.

Project for historical revision

A better understanding of seventeenth-to-eighteenth-century Catalan history and the obsolescence of the concept of decadence which, since the Renaixença, has prevented us from grasping the originality of these two centuries, has been closely linked to the knowledge of 1714 derived from the El Born project over the last twenty years. Work carried out for the Olympic Games uncovered significant fragments of the city demolished by King Philip V. This discovery, combined with the systematic excavation of the old El Born market undertaken in 2002, has facilitated the reconstruction of the daily life of the former La Ribera district inhabitants. This, and the analysis of the everyday life of the parish of Santa Maria del Mar, has allowed us to make sufficient progress in learning even the most minute of details: we know, down to names and surnames, who lived in each house, what they did there and what the household furnishings were like. The notarial archives of Barcelona are the most comprehensive in Europe, surpassed only by those of Genoa, Italy. The fact that they contain the full archive of the parish of Santa Maria del Mar, plus the good state of conservation of the archives of the former College of Surgeons, has enabled us to make headway in positivist research and in gathering micro-history on a level that was unthinkable not long ago.

© MUHBA / Pep Parer

A fragment of the anonymous painting of the Bornet, dating from the early 18th century. The work, held at the Barcelona History Using, reflects the intense commercial and social dealings in this area of central Barcelona in the past, which is now the Passeig del Born.

The project to convert El Born into a museum faced a sad urbanistic, bureaucratic and political fate characterised by unjustifiable delays that went on for far too many years (now resolved with the official opening of the Born Cultural Centre). That being said, these impediments permitted a much more in-depth study of the archives and materials, without which the traditional historiographical theories might not have been refuted so readily. It is only fair to acknowledge the work of Albert Garcia Espuche in this overall context, to whom the city of Barcelona and modern Catalan historians have an unpayable debt. Thanks to him and his team, we can now categorically say that Barcelona (and by extension, the whole of Catalonia) was not decadent in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Rather, it was a city that opened Spain’s first cafés, that boasted some twenty wig makers and where over sixty different types of tobacco were sold. It might have been many things, but decadent was not one of them.

Prosperity and cosmopolitanism

Detached from the network of power and courtly pomp, Barcelona, and by extension Catalonia, became prosperous thanks to the citizens’ willpower. Like so many other Dutch and Italian cities of the time, Barcelona – and Catalonia – chose hard work over honour before and after 1714. The Bourbon storm spawned misery, but Barcelona in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as described by the notarial archives, was a city at the heart of an extensive commercial network with resources, brisk trade and a cultural tradition and cosmopolitanism that not even the most absurd Bourbon actions could stifle. By no means did Catalonia’s defeat in 1714 or the new Bourbon economic framework produce the eighteenth century’s economic development, as was asserted by Pierre Vilar, but rather it was the growth and inclusion of Catalonia in the industrial revolution that resulted in the final outcome of an existing prolonged wave, and can only be accounted for by the formidable accumulation of energy over two hundred years of constant work and innovation. Today, this assertion is fully documented, and the La Ciutat del Born. Barcelona 1700 collection (published by the City Council of Barcelona, recently with the support of the Fundació Carulla and Editorial Barcino) is an important tool in the renewal of this period’s historical studies.

© Ramon Muro / AHCB

Gaspar Ferran, militiaman of the company of silversmiths of the Coronela de Barcelona, in a volume from 1707 held in the same archive.

Eleven volumes – ten of which have been published so far – featuring articles by the best specialists, document to an almost exhaustive degree the history and culture of Barcelona during the century leading up to 1714. Moreover, they do so from the perspective of everyday life. Methodologically, the texts also evince the maturity of a Catalan historiographical school that creatively uses the techniques of micro-history and the history of mentalities, overcoming the limitations of Marxist economic veterohistory. In the study of any culture of any country, it is difficult to find over forty competent and well-coordinated authors for a common project, and even more so when one is aware of the limitations and precariousness present in Catalan academia, which is perpetually underfunded. This makes the project even more significant. In literary terms, the texts are very clear, readily accessible to non-specialists and exude the nostalgia of everyday life that makes for pleasant reading. In the hands of a novelist, this collection is a veritable gold mine as it expounds the customs and mentalities of the period, and also for the light that it sheds on our present. Small details make for great stories, and meticulous explanations on trade, fashion trends or even coffee and tobacco in Barcelona in 1700 allow us to gauge the beat of a lively, cosmopolitan and diverse city, at least as diverse as the Italian and Dutch city-states of the epoch could have been. The merest circumstance, the Balzacian detail or the petit fait vrai of Stendhal that the novelist needs nestle in the notaries’ documents – the historians recover all of this.

It is well known that books only serve their purpose if the reader continues to contemplate and dream about them even after they have been set down. It is self-evident that La Ciutat del Born collection contains material for fine novels and can provide food for thought on the country’s cultural continuity. It also seems evident that this publication constitutes a historiographical watershed. However, what we will most owe to Garcia Espuche and his team is that the sad label of “decadence” can now be tucked away in a drawer. Which is no small debt.

All the titles of La Ciutat del Born. Barcelona 1700

1. Gardens, Gardening and Botany.

2. Dance and Music.

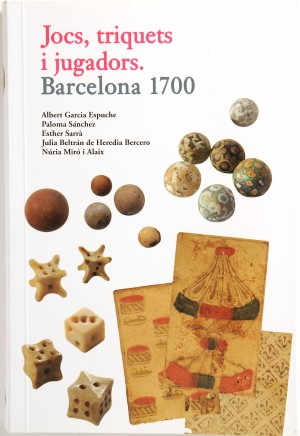

3. Games, Ball Courts and Players.

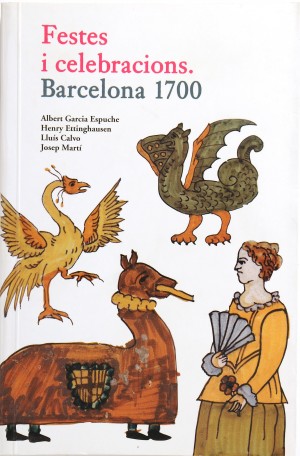

4. Festivals and Celebrations.

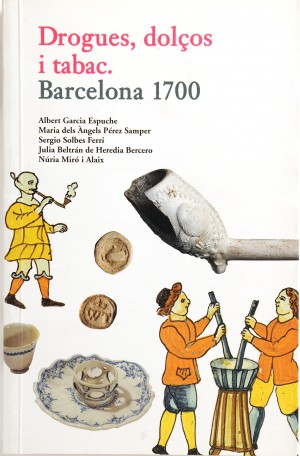

5. Drugs, Sweets and Tobacco.

6. Language and Literature.

7. Medicine and Pharmacy.

8. Domestic Interiors.

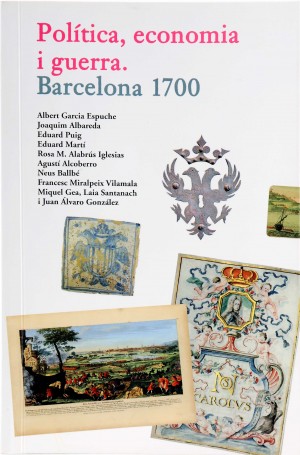

9. Politics, Economics and War.

10. Clothing.

In preparation:

11. Law, Conflicts and Justice.