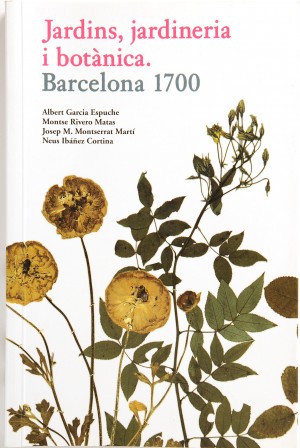

Jardins, jardineria i botànica [Gardens, gardening and botany]

Jardins, jardineria i botànica [Gardens, gardening and botany]- La ciutat del Born. Barcelona 1700 Collection

- Albert Garcia Espuche (director)

- Barcelona City Council. Museu d’Història de la Ciutat

- Barcelona, 2008

- 229 pages

Jardins, jardineria i botànica (2008) is the first book in the collection La Ciutat del Born. Barcelona 1700, a series in which ten volumes have been published hitherto with a twofold purpose: to publicise and situate the findings uncovered in the El Born excavation site and to put the Barcelona of the 17th and 18th centuries in context based on micro-history and on a detailed understanding of everyday life, particularly with the help of notarial and guild archives. The first book features the participation of Albert Garcia Espuche, Montse Rivero Matas, Josep M. Montserrat Martí and Neus Ibáñez Cortina. The volume ends with the transcription, by X. Cazeneuve, of the anonymous manuscript from 1703 entitled Cultura de jardins per governar perfetament las flors, arbres y plantas per la constel·lació de Barcelona [Garden culture to perfectly govern the flowers, trees and plants for the constellation of Barcelona], a veritable gardening manual, the work of a fine amateur, who gives detailed descriptions of the world of flowers and plants “for anyone who wants to have a harmonious and tidy garden”. This text features an interesting prelude in the form of an article by Montse Rivero, Cultura de Jardins. Les anotacions d’un jardiner [Garden culture. A gardener’s notes], which shows, for example, that the climate of Barcelona (a bit colder than it is now) was suitable for growing orange and lemon trees without any kind of winter protection.

It is significant that the concept of garden, counterpoised to that of the vegetable garden, should emerge at the beginning of modern times. A garden is a space dedicated to ornamental flowers, with a certain architectural organisation of its space, and with a recreational objective. The vegetable garden, on the other hand, is a space for subsistence agriculture, for growing food, and is often used recreationally by elderly people who cannot get out into the countryside. The garden, based on the Versailles, Italian or Central-European model, has always had a symbolic function, and denotes status; it conveys an urban and courtly sensitivity. The vegetable garden, on the other hand, is related to difficult subsistence in rural and hermetic societies, often troubled by the spectre of famine. The garden is urban, whereas the vegetable garden is peri-urban.

There is something intimate and unassailable in the garden, so that seeking reclusion in the hortus conclusus, the “secret garden”, alien to the sounds of the world, often provided classical men of letters with the exact gesture and metaphor for the sensitive soul. We do not know what the Epicure Garden was like, a model of harmony and friendship par excellence throughout the centuries, although it is known to resemble more the vegetable garden, rather than what we would identify today as a recreational space. But the platitude of the pagan hortus amoenus (a mixture of library and garden, in a letter by Cicero) quickly came to grief at the hands of the barbarians and did not reappear until the Renaissance. The medieval Christians and the first humanists who, like Petrarch and Boccaccio, regarded nature as a perilous place, reconstructed (perhaps using an Arab matrix) a veritable mythology of flowers and garden that they used as a space for pleasure, entertainment and social interaction. The maze was both a symbol and a society game.

Knowing that in the course of the 17th and 18th centuries Barcelona was a true “garden city”, where flowers were imported from everywhere, and several indigenous tulip varieties were created, signifies at least three things: that it was not a densely populated city (the city’s densification was yet another one of the consequences of the defeat in 1714); that it was a pleasant and rich city, whose citizens were sophisticated enough to have time and money to engage in cum dignitatem recreation, and finally that it was a city well connected with the world, that imported fruits and seeds that were cultivated by its gardeners. Pere Serra Postius described (between 1734 and 1748) the vegetable gardens of Fusina, near the Ciutadella, saying that “there could hardly be a more joyous and delightful place to walk in anywhere else in the world”. The waters of the Rec Comtal irrigation channel guaranteed a continuous supply to the city, and we know, as this volume also describes in detail, that for many traders the hort de regalo (ornamental garden) was a small but affordable luxury.

If gardening is a synonym of civility, and the flower is an expression of good taste, then there is no doubt that the Barcelona that tended to its horts de regalo, with anise, lavender, orange flower and rosemary plants in its houses, was an eminently civilised place. The defeat of 1714 was not merely a political and institutional calamity. As is wont to occur in all wars, it was also a civil calamity.