El barri de la Perona. Barcelona 1980-1990

El barri de la Perona. Barcelona 1980-1990

Authors: Esteve Lucerón (photography), Àngel Marzo (text)

Publisher: Barcelona City Council and Marge Books

176 pages

Barcelona, 2017

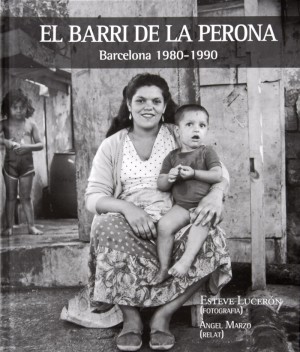

Esteve Lucerón recovers the last few years of the gypsy Perona, when the neighbourhood had been living amidst conflict and exclusion for quite some time, and does so without prejudices and in a natural manner.

It seems strange to evoke a neighbourhood that disappeared due to embarrassment. Not a neighbourhood that has transformed itself to such an extent that it is no longer and will never be as it once was, but one which has been eliminated from the very root to give way to a sleeker, more anonymous and indifferent urban aspect. Transformations are what regulate urban life and a city changes so much faster than a human heart, but it tends to retain some part of the heart and the insides that have made it what it is.

Not in this case. We talk of an urban life that doesn’t exist, one with no streets or houses, no bars or markets, no children, adults or elderly, no police or teachers, no passers-by or neighbours; a life without people. Without problems. Rather, only the typical problems of a park, the Sant Martí park that has replaced it. We’re talking of La Perona. Nowadays seen in photos and records.

La Perona disappeared in 1989, year in which the huts still standing in Barcelona were finally demolished, leading to the visible step taken towards the Olympic event and the new city which has since then emerged. Before the Olympic Village and the urban opening onto the sea, the first images that announced the change that was coming were photographs of the Mayor Pasqual Maragall at these public sites during the demolition of La Perona huts, among the most widely recognised. Others were ones such as the Carmel, Montjuïc, of remaining spots of the Diagonal. The destruction cleaned and cleared the path.

La Perona neighbourhood no longer existed as of then, neither did Somorrostro, the inhabitants of which were relocated alike those of La Perona when the huts and camp sites that had been erected along the seaside were removed on the occasion of Franco’s visit in 1966. Gypsy settlements.

That Perona now lives in the archives, in the private images of those who lived there, in the scarce recorded material available. And especially in the photographs taken by Esteve Lucerón, now compiled into the book for which these lines have been written. With the disappearance of this neighbourhood, the inhabitants were relocated to the homes provided by the City Council to eradicate the huts they had built themselves. El barri de la Perona. Barcelona 1980- 1990 comprises a worthy selection of photographs which Lucerón has released to the Photographic Archive of Barcelona and are accompanied by very experienced texts by Àngel Marzo. A photographer trained in the highly active dynamics of the International Photographic Centre of Barcelona who decided to document the lives of the gypsies living in La Perona and that is what he has done, immersing himself in the neighbourhood as an occupational workshop teacher, and a writer who was a teacher at the Adult School of La Perona.

Located along the length of the Sant Martí district, between Espronceda bridge and Horta river, where we now find the park and part of the Sagrera railway tracks. La Perona received its name not thanks to the sweet nun as was thought for years, but due to the visit by Eva Duarte de Perón, who was referred to as “la Perona”, to the Franco regime in 1947. This site had already been chosen by the peninsular migrants of the post-war period, who made up La Perona of gorgers, which remained until 1967. As of which mainly gypsies settled there, until the settlement was removed.

Esteve Lucerón recovers the last few years of the gypsy Perona, when the neighbourhood had been living amidst conflict and exclusion for quite some time, and did so without prejudices. His photographs recover that life with great naturalness, following along the line of the strength arising from experiences sustained by each family –“which is a tree”, in Marzo’s words– and by children that grow up accompanied by the caring eyes of their grandmothers, who represent “the connection with the line of a time that doesn’t end”. Plenty of sun shone on that gypsy tarmac, not only the shadows of conflict

In the park that ends the photographic collection there are several neighbours, I imagine, and also the migrants who once again make a living from scrap iron in Sant Martí and Poblenou, the new nomads of Barcelona, now arriving from the diaspora of global poverty.