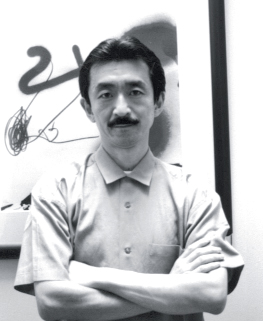

Ko Tazawa first came to Barcelona in 1978, when he was sent by his bank to learn Spanish. His contact with Catalan society would lead him to love the country, its culture and language. He has been back twice, most recently in 1993, with his wife and two children, to take his PhD in Catalan philology.

I am Japanese. I am 59 years old. I live in Kobe, Japan. I am a university lecturer and Catalanophile. I mainly work on translating Catalan works into Japanese and vice versa, and I write books to present Catalan culture to Japanese people and vice versa. My relationship with Barcelona has been ongoing for over 30 years. Despite all this, perhaps I am not the best person to write an article on how people from Japan see Barcelona. Allow me to explain. To do so, there would have to be a certain distance between the city and me. It is true that I live physically in Japan, but emotionally there is less distance between me and Barcelona than between me and Tokyo (about 600 kilometres from Kobe). So what you are about to read is a very personal view of the city…

I have known three different Barcelonas at three crucial times in my life.

The first encounter was in 1978. I was working in a Japanese bank at the time. I was sent to Barcelona to learn Spanish (!). Barcelona before the Olympic Games was, in a word, dark. Perhaps this impression was caused by my state of mind, my anxiety, because I had to learn Spanish, which I had never studied, and then start to work in the Madrid branch of the bank six months later.

It was at the time of the referendum on the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia. Catalan could be seen and felt in the streets. And not only that. Street names were changed from Spanish to Catalan overnight. Sometimes they just stuck the paper with the street name in Catalan over the marble plaque bearing the old name. I was fascinated by such scenes. “Here you can get a first-hand look at the close relationship between language and society!” I thought to myself. That experience changed the course of my life, because it made me realise that I was not really interested in the job in the bank, but rather in languages.

The bank’s intention of having another Spanish-speaking employee was thwarted, because I gave up my job there within a year of returning to Japan. I signed up for a postgraduate course at a university. I knew what I wanted to study: Catalan sociolinguistics.

The second contact with Barcelona was after I had some knowledge of Catalan. I had studied with books and cassettes but had never actually spoken it in Catalonia. I had a subscription to the Avui newspaper and was an avid reader of Josep Maria Espinàs’s “A la vora de…” column. One day I decided to write to him to ask him to help me find a family to stay with in Barcelona so I could get some hands-on experience in Catalan. The truth is that I did not expect to get an answer from such an important writer. Indeed, a week, a fortnight went by… with no news. However, on 13 March, 1990, when I opened the newspaper I saw my name in his article. Not just my name, but my entire letter. Mr Espinàs was asking his readers to put me up in their houses. Within a few days I received a score of letters from families offering me the chance to stay with them. There was even a restaurant owner who invited me to dine at his establishment every day!

Making a choice was really hard. I eventually chose the most central house, on carrer Pau Claris. The family was a very Catalan middle-class family. The lady of the house was a superb cook. She strived to offer me the broadest possible variety of homemade Catalan cuisine: meatballs, macaroni, cannelloni, rice, crème brûlée, and so forth. The man of the house was a businessman with the typical morality of the Catalan bourgeoisie in the best possible sense: love of a job well done; love of the family; and love of God. I spent a fortnight there. It was very short but very fruitful. My knowledge of the language, culture and people of Catalonia improved. Barcelona didn’t seem as dark as before.

This encounter yielded a by-product: Josep Maria Espinàs asked me to write a book about my experiences in Catalonia. The result is Catalunya i un japonès [Catalonia and a Japanese Man] (La Campana), which, much to my surprise, became a minor bestseller.

The third encounter was around 1993. I had started to teach Spanish at a university in Osaka. I was married and had two children. Fortune had smiled on us, but I felt the need to get to know Catalonia better. I would have to do a PhD in Barcelona, and to do so I would have to give up my job at the university. Finding the job had not been easy, and if I left it there was no guarantee that I could go back to it.

I had already compromised the stability of my life when I gave up my job at the bank. At that time my wife had been very understanding. However, this time things were quite different, as we had two children, aged six and three. Nevertheless, I knew that I would never make any progress with my Catalan studies if I stayed where I was. Finally, I talked to my wife about it and she agreed. It could not have been an easy decision for her. I am grateful to her to this day.

Destination Barcelona! The four of us set off on the new adventure. It was a challenge for me, of course, but it also was for my children, Yu and Kei. Neither of them spoke Catalan or Spanish. Taking them with us meant removing them from a totally Japanese environment and plunging them into a new one, a Catalan one. In the beginning, Yu did not even know how to ask where the toilet was and when he felt the need, he had to follow a classmate who looked like he was headed there. Kei used to cry every morning when we left him with the girl from the kindergarten. The poor thing must have wondered why the people around him did not have slanted eyes and why they spoke a language he could not understand. However, after six months both of them could get by in Catalan in their own way. My wife, who spoke Spanish, also made a great effort to learn Catalan.

The fact that we had children gave us extra opportunities to broaden our range of activities. We made friends with the parents of many of their classmates. In Barcelona, unlike Japan, people ask you to their house so the children can play. This helps to break the ice. If your child tells you he wants to play with a friend, you have to mix with the child’s parents even if you don’t know them very well.

Thanks to the collaboration of my wife and children, the three-year stay in Barcelona was a complete success, I got my PhD in Catalan Philology from the University of Barcelona. However, more than anything, we all had marvellous experiences there. If Barcelona seemed brighter than it used to be, it couldn’t only be due to the “Barcelona posa’t guapa” [Barcelona, get pretty] campaign.

Our children have kept up their friendships. And we have more friends in Catalonia than in Japan. My wife says that she feels more comfortable in Catalonia, because people say what they really think and feel. In Japan, more often than not you have to guess what lies behind other people’s words. For my wife, a very straightforward person, this custom is difficult to accept.

When will our fourth encounter with Barcelona be? Our children are independent now. Retirement is nigh. For us the ideal would be to live between Barcelona and Kobe, with me publishing translations and texts.