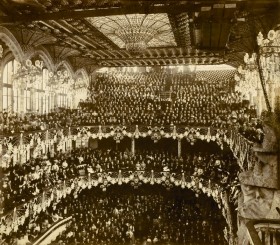

It took a while for melodies from distant lands to reach my shores. The Italians were the first to give me the gift of opera, initially at the Palau Reial and then at the Teatre de la Santa Creu. The “cruzados” (“crossers”, as the 19th-century playwright and theatre impresario Pitarra referred to those who attended the Teatre Principal, formerly the Teatre de la Santa Creu), and the liceistes who went to the Liceu almost came to blows in those heady days of operatic glory. Quite soon, of course, and especially at the Liceu, there was a great deal of Wagnerian waffling, which allowed me to get all dressed up in my modernista architecture, with its frequent references to the myths which had so inspired Wagner himself.

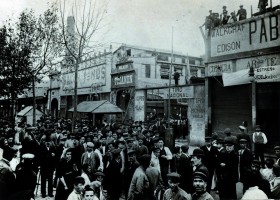

But that very serious side also created echoes in popular music, starting with a choral piece by Clavé and culminating in the “casa dels cants” (or song house, as Maragall described the Palau de la Música Catalana). Not to speak of the first batches of musical “rebels” to be found at the music halls on Paral·lel where La Bella Dorita sang out her thinly veiled innuendo, or the first jazz notes I heard in places like the Rector’s Club at the Hotel Palace, with what they used to call the “negro” orchestra (such naivety!).

They also developed my mind: at the Institut Francès, for example, members of the Cercle Manuel de Falla discussed their intellectual concerns with those of the Dau al Set society. Lucky we had those people, who strived to bring the echoes of true modernity from France and Central Europe, while the musical programme at the Palau de la Música became paltry and that of the Liceu was simply the result of the job of an impresario who did what he could but could only fill this coliseum with bohèmes and traviatas… Naturally, the little lords of the Liceu, with their lovers whom they set up in business with a tobacco shop, continued to frequent the El Molino music hall, where La Bella Dorita continued to dazzle audiences with her patently artificial innocence, as she sang those couplets so clenched by the iron fist of the censor of the day.

© AFB

Alongside, the hubbub of the Avinguda del Paral•lel mirrored in a photo taken by an unknown author at the beginning of the last century.

I carried a little of Xàtiva, Verges, Palma de Majorca and Poble-sec inside me when Raimon, Lluís, Maria del Mar and Joan Manuel appeared. They’ve all walked my squares and streets and settled here while they forged the Nova Cançó or New Song, the Catalan protest song movement, in venues like the Cova del Drac. They were good lads and lasses, very different to those high-class people who were having such a good time with the new sounds of English and American rock on that first ring road they gave me, the Ronda del General Mitre, where it crossed carrer Muntaner: it was the heyday of the Boccaccio club. But it was the gang that formed part of the rock laietà movement (Catalan jazz-rock of the 1970s that emerged in the bars around Via Laietana) that gave me a badge I still wear with pride.

Then fire broke out in the Liceu, and it was all sobbing and beating of breasts in front of the smouldering ruin. So they decided that the Liceu of the few would be of the many and for the many. In the meantime, they built me the Auditori, although they put it in a place so lacking in charm that even today I have to whisper in the ear of some uninformed taxi drivers to guide them to the building that someone said was as long as the Titanic (let’s hope it doesn’t end up the same way!).

All of that happened like a hangover after a drunken party that actually turned out to cost me a lot: I’d a great time when they lit my Olympic torch, but after that I wasn’t in the mood for forums, because I could see where they were going: too much on offer for too few people, although the Primavera Sound and Sónar festivals still give me a nice, tickly feeling.

But what I see is too much inertia and I can hardly stifle my yawns when it comes to the programme at the Auditori, which seems far too predictable. I try to miss it whenever I can and only go for ceremonial events, the ones you can’t miss even if you want to. They did what they could, but the fact of the matter is that when I wander around its environs, I always see the same people who go to the Palau or, occasionally, to the Liceu.

True, we have the facilities we should have, but ultimately they are containers with no content. Not to speak of their disastrous management (in some cases worthy of the worst days of gangsterism), starting with the Palau de la Música and that character who goes by the name Fèlix Millet (“Fèlix Bitllet” or Felix Banknote, as can be read on the plaque just opposite the concert hall designed by Domènech i Montaner). Or the dreadful management of the Liceu… What’s going on?

Meanwhile, aside from the electronic and alternative music festivals, I content myself with the teen scene that’s still tripping the light fantastic in clubs like Sala Apolo, Be Cool, Razzmatazz and Luz de Gas. Of course they’re kids who hear but don’t listen and maybe they’re not aware of today’s musical reality. Nor, I must confess, am I: I spend too much time on my iPhone downloading new tracks I may only listen to once, and those songs by our local bands don’t make or create much of an impression. When it comes to music, I’ve become a prophylactic city: use it and bin it.

I’ve always been, I like to boast, a city that has given the world many good musicians. And that has welcomed many others. And it could stay that way if those looking after me made me more attractive, musically. They could do that by giving the Auditori a concert infrastructure with a range of programmes that combine the traditional and the modern, taking the risks inherent to any arts facility. It is also time to clean up the Palau de la Música, from the first to the last stone, restoring the dignity it should never have lost. I also hope that in the future, cultural programmes will interact with each other thematically: it would be fascinating to see the Filmoteca, the Centre de Cultura Contemporània or the MACBA align themselves with the Palau, the Auditori or the Liceu when scheduling performances or exhibitions, so that the programmes are thematically linked. Now that all that is cross-disciplinary is in vogue, we should leave something to our children or grandchildren to make them more cultured, enriched, free, alive and happy.

© Pepe Navarro

Concert by the group Standstill at the 2007 Primavera Sound festival, in the Fòrum park.

But none of that can be done if they don’t care for my musical schools a little better. ESMUC (Catalan College of Music) needs a total spring clean, the Liceu’s Conservatori has a new building and many people still don’t know where it is, and no-one even seems to remember my dear old conservatoire on carrer del Bruc. Of course, the music curricula in schools make you want to weep, and we have reached a situation which, if things stay the same, will lead to a dire education for our young people in the future.

As I said at the start of this section in which I dare to dream of the future, I’ve been a city of musicians or a city that has welcomed musicians. And a city with strongly rooted forces committed to modernity, risk and the avant-garde. I promise I will clean my face more often and not open up so many holes in my streets, clogging up the traffic; but in return, give me back that risk and that perspective from two steps ahead that young and not-so-young creators have. Let them gather once more at festivals or meetings of truly contemporary music, so that I may continue to know that I’m at the forefront; a mirror for musical creativity within and beyond the borders of this country of which I want to remain (and proudly so) the capital and the family seat.

“It is a city that has generated and welcomed musicians, committed to modernity, risk and the avant-garde”

The “great enchantress” is not wrong when she contemplates an apparently stagnant present and a very uncertain future. The blunders and gaffes that have sent music in Barcelona down a blind alley are certainly not due to a lack of talent or to the schools, which have highly skilled, tried and tested professional teachers. Nor are they due to a lack of facilities that can host many events and house large audiences. No, it’s an administrative and political problem. When certain suited men fiddle with things that don’t concern them, the music stops and inexorably remains at a terrible bar rest. This goes for any activity in the arts or any other field.

© Ariadna Borràs

Opening concert of the 40th edition of the Barcelona Jazz Festival in October 2008, in the Parc del Centre in Poblenou.

Music and the running of music venues should be left to the experts or to artists who are qualified to manage them. Right away, young musicians must be guaranteed a stable job and opportunities to further themselves here. Music programmes are systematically ignoring the creativity of those well-educated youngsters who come out of city schools. It would not be too much to commission from them pieces to be performed alongside the great works of history.

As well as the more iconic venues, we need to reactivate music’s presence in neighbourhoods: in the reclaimed courtyards of the Eixample, for example, or in parks and gardens (as we did in the 1990s) when the good weather comes. Music should be taken out of its hubs and moved into the daily lives of the public who don’t want to or are unable to get to a large auditorium or theatre, for reasons of affordability or convenience. We know that the Catalan capital has never been and never will be Vienna, Berlin, London or Paris. But everything possible must be done to ensure that Barcelona never stops being what it has always been: a music-lover.