–Lovely enchantress, here we are again. Make yourself comfortable. Would you like to sit on the chair or the couch? You’re panting, your tongue’s hanging out.

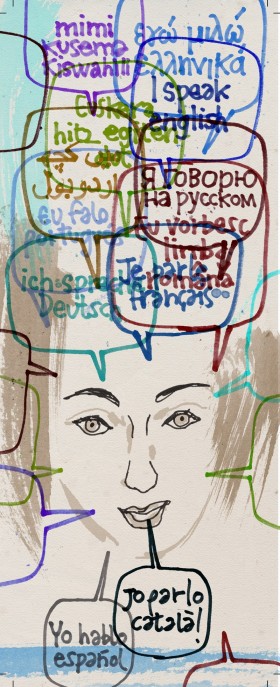

–My tongue… yes. They say I’m a multilingual city.

–Multilingual? Saying you’re a multilingual city is a very elegant way of burying your head in the sand. Take a seat on the couch.

–On my streets, one hears Amazigh, Swahili, Italian, French, Urdu, Russian, Spanish, Arabic, English… There are so many languages, they even speak Catalan!

–You’re in a jokey mood today. Why so facetious?

–Some people are amazed. Even for me, it’s something of a miracle that, after so many centuries and such a history of prohibitions and persecution that the Catalan language has suffered, I can still hear it spoken on my streets. Because, while I enjoy listening to the phonetics of Kikongo and Ronga, of Spanish and English, I especially love the sound of Catalan as it is the city’s own language. We speak lots of languages here now, but Catalan has always been spoken here.

–Always?

–Since Latin became a crucible for the Romance languages. In the Middle Ages, Barcelona was the capital of a kingdom that spread its empire around the entire Mediterranean. The Catalan kings and queens were among the first European monarchs to turn away from Latin for the writing of their royal chronicles and adopt the language spoken by their subjects. The royal chancellery helped to consolidate a language that is still shared by Catalans, Majorcans and Valencians today. Catalonia’s age of splendour came early (maybe even prematurely) because the Crown of Catalonia and Aragon had its moment of glory before the creation of the modern nation states that have ultimately drawn the map of Europe, either with wars or with blows of romanticism. The French worked out how to “civilize” the Bretons, the Occitans and the people of Roussillon. The Spanish have not quite managed to “civilize” the Catalans… Exactly 100 years ago, in 1912, Pompeu Fabra published the first modern Catalan grammar. He wrote it in Spanish, so that everyone could understand it and it wouldn’t go unnoticed by those who needed it or those who had to acquaint themselves with it. The people of Barcelona have always made an effort to explain to the world that Catalan isn’t just a dialect. Take the Olympics, for example.

© AFB

Retrato de Pompeu Fabra, de autor desconocido, realizado en un año indeterminado del segundo decenio del siglo pasado.

–Now you’ve put your finger on it. So tell me, what’s on your mind?

–I don’t want to lose my calm. Officially, I am a bilingual city. I have my own language: Catalan. And another one that I share with the other towns and cities in Spain. It’s a balancing act. Some tell me I should embrace Spanish more (the Spaniards call it “the common language”). More people would understand me, but I can see that when I speak my home language, everyone here still understands me. Catalan is also a common language. Why give it up? Some people want to make it into a problem and others have always seen it as the solution.

–You mean some have seen language as the solution to the problem and others see it as a problem to be solved.

–Thinking that the language is the problem is just as dangerous as believing it’s the solution. In Barcelona we’ve been talking about the normalisation of the Catalan language for 30 years now. It’s relatively easy to normalize the institutional use of the language in government and schools, but obviously people can’t be normalised. A fireman can’t be normalised, a judge can’t be normalised, a footballer can’t be normalised.

–Is that the problem? Would it be enough if Messi spoke Catalan?

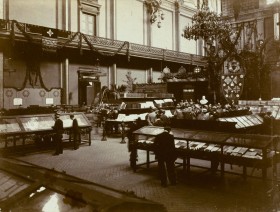

© Frederic Ballell / AFB

Catalan bibliographic exhibition organised in the Palau de les Belles Arts of Barcelona for the First International Congress of Catalan Language held between 13 and 18 October 1906.

–At the moment, I’m more concerned about demographics and grammar than language policy. Catalan has to consolidate a critical mass of speakers if it’s to retain its place in public life. If not, it runs the risk of becoming an official marginal language. You know what the matter is? More or less everyone understands or speaks Catalan but those who can speak it don’t always want to. And many who do speak it, willingly or otherwise, don’t speak it well enough. Or they half-speak it.

–And what’s more important, the quantity or the quality of speakers?

–That’s one of my dilemmas. For decades, my leaders have gone for quantity. They acted in the belief that Catalan, which initially looked like an obstacle to integration, was in fact the solution. It’s true that today in this city, no-one can work in any position of authority, be it in public service or the media, without understanding Catalan. Seen like this, normalisation has been a success, but along the way we’ve sacrificed weak pronouns and contaminated syntax.

–The Catalans are pricking up our ears. What’s more important to you: correct use of language or having the courage to speak?

–Don’t make me choose. Someone said that the main threat to a language’s survival isn’t the people who don’t speak it, but the natives who speak it badly.

–Who does the language belong to? To those who know it well or those who just get by?

–To those who love it. I’d be happy if everyone understood that, however much of a polyglot I am, Catalan is my language. I would love it, for example, if the city authorities didn’t have to contest or debate the use of the language.

© Julio Parralo

Catalan classes are one of the activities organised in Poble-sec by the Bona Voluntat en Acció organisation, which works untiringly to promote the social integration of the more underprivileged in the neighbourhood, most of them immigrants from abroad.

–Listen, lovely enchantress. This is now your life coach talking. Do you really think that regulations on the use of language alone can save the Catalan language? The legal protection is already in place because there is consensus; the people have wanted it that way. Your language won’t be saved by laws or Catalan language exams alone, but by love. Conquering the public domain is no longer so urgent, but preserving those spaces ruled by affection for the language is: better a teacher’s hug than a judge’s sentence. Better to win in the playground than smash TV viewing figures. Some thought we needed to normalise the newcomers, but normalisation begins with the Catalan speaker, the homo faber, to put it in Darwinian terms. Those who speak it see Catalan as a right and those who don’t see it as a somewhat burdensome duty. It should be the other way round. Those who don’t know it should see Catalan as a right. And those who’ve spoken it their whole lives and boast about its survival should see it as a duty.

Catalan has to be actively defended by your citizens: speaking it and not just speaking of it. Languages are markets and Barcelona’s Catalan speakers must decide, individually and collectively, in which city they want to live. If homo faber had boycotted the cinema until he was offered films dubbed into or subtitled in Catalan, we wouldn’t have had to draw up the cinema law. If homo faber chose to buy products labelled in Catalan, manufacturers would soon notice and take action. Why do Microsoft and Google offer their products in Catalan and yet it’s hard to find a tin of peas labelled in Catalan? What interests me more than the attack of Catalan is the mark of Catalan. Making a mark. Being a recognized market.

You know the problem, lovely temptress? We’ve handed out level C certificates in Catalan language as though they were Catalan identity passports. Now we find that many of your citizens have learned the language without the need to feel Catalan. Is a Catalan person just someone who speaks Catalan? Can one learn Catalan without feeling like a Catalan, purely for administrative merits? The language is off on its own, flying away. We must try to stop it from getting caught up in feelings. We mustn’t pass on our aches and pains to it. We must open up paths for it, without identity checks. Our language is the greatest legacy that Catalans will leave mankind. It’s not only ours any more. And with the fellow citizens who don’t speak the same language, because they don’t know it or find it difficult, we’ll still understand each other if we speak the same language. The language of respect and of love.