The Sant Andreu cricket club training on the Pérez de Rozas baseball pitch on Montjuïc, in a photograph taken in 2016, with captain Sajid in the background. This is one of the cricket teams formed by young Pakistanis with backing from the City Council.

Photo: Pere Virgili

Today, Barcelona houses more foreigners than newcomers from other parts of Spain. Globalization has irreversibly changed the demographic face of a city that became a magnet for migratory movements from all around the world this turn of the century.

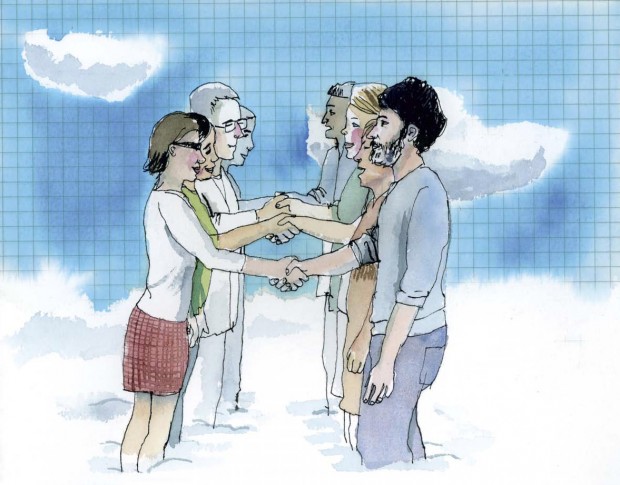

“We’re fortunate enough to only have been receiving immigration since relatively recently, if we compare ourselves with London or Paris. These are two cities with a colonial past that even today are faced with significant difficulties in managing diversity”, explains Lola López, commissioner for immigration at the Barcelona City Council. While France opted for the assimilation of newcomers, England opted for multiculturalism. The years have shown that neither recipe has prevented segregation or guaranteed social cohesion.

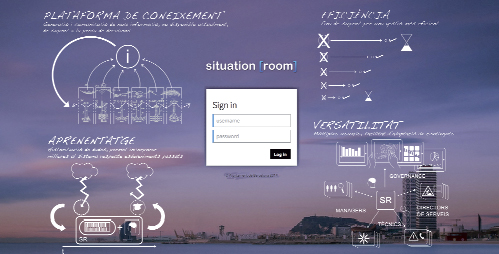

For over ten years, the Barcelona City Council has invested in interculturalism. The Municipal Plan for Interculturality has been an irrefutable foundation for city politics over the last decade. “We need to try and avoid the errors of other models”, insists López. “The first thing we need to do is to not see interculturality as a closed model, but rather as a process. This model is under construction, and we need to encourage citizens to participate. We don’t apply intercultural policies, we organize actions from an intercultural perspective. This model is so open that we can decide to abandon it at any point.”

The first tenet of interculturalism is not to exclude either the multicultural option or assimilation. “Whoever wants to assimilate with the local culture has to be able to do so. We also won’t put up any obstacles to multicultural coexistence. If a community choses to live more closed off in its own space, —always within a shared context— they need to be respected, because that’s a natural tendency that we all have when we migrate”, sustains López.

Three levels of interculturality

Interculturality is applied on three levels. First, we need to guarantee equal rights and equal access to opportunities. This first value is essential, and it’s shared by the French assimilationist model and the multiculturalist British model. The second requirement for building an intercultural dynamic is the recognition of cultural and religious diversity as an asset.

Finally, the third level of interculturality demands interaction and dialogue, so that all communities can contribute to the construction of our city without leaving behind who they are. “Dialogue demands the recognition of the other as an equal. Interculturality isn’t easy, it has plenty of areas of conflict” states López. “We constantly need to be building this dialogue, recognizing the value of diversity. We still haven’t realized, for example, that the Colombians, with the baggage of conflict they carry with them, can provide us with tools for conflict resolution. Or that we can learn strategies for community survival from newcomers from sub-Saharan Africa, a group that didn’t return to its countries of origin with the 2008 economic recession because it was better able to resist it than others”, concludes the commissioner for immigration.

Barcelona is a fertile field for intercultural relations. The Chinese New Year, which is celebrated in the Fort Pienc neighbourhood with a parade, combines dragons, castellers and diables. The City Council has gotten involved, promoting the celebration: “You offer the Chinese community the opportunity to celebrate something of their own, in a real way, and they open the door to incorporating ingredients from the country that has received them. As a result, a sense of belonging is created in both directions. The city makes the traditional celebration of one community its own by adding local elements.”

Another successful example of interculturality can be found in the Pakistani community, which has watched its youth begin to play cricket around the city, eventually creating the Poble-sec Cricket Club or the Sant Andreu Cricket Club, among others. The City Council has provided these youths with spaces and has organized a program for teaching sports monitors to play cricket. Most of these monitors are also Pakistanis who see that their skills are recognized, and that the work they do is respected. As a result, Pakistani children see these monitors as positive figures who help them to identify with their community. The City Council has promoted a female cricket team, which has also incorporated girls of Moroccan and South-American origin. This has brought about a change in how others see Pakistanis, bringing them to value their abilities. This program embraces all phases of interculturality, since besides guaranteeing citizens’ rights and equality, it places value on diversity and integrates other communities into this space for interaction.

The exercise of interculturality also takes into account religious diversity. During Ramadan, Muslims in Barcelona celebrate Iftar (the breaking of the fast) with a celebration in the streets open to everyone, where they serve dishes typical of their countries of origin. Different experiences of death also result in different ways of understanding funerary rites; the Mexican celebration of the Day of the Dead invites us to honour the deceased in a more festive manner than we are used to.

Chinese New Year Parade in the Sagrada Família and Fort Pienc neighbourhoods in February 2014.

Photo: Pere Virgili

Citizenship and culture

Our cultural identity is an important ingredient in our citizenship. Toby Miller, a professor at the University of California, distinguishes between three different types of citizenship. First is political citizenship, which considers the rights and obligations of the individuals in a certain community. Second is economic citizenship, which should guarantee the survival and welfare of the citizens of a country. Finally, third is cultural citizenship, which should guarantee the feeling of cultural belonging.

Cultural citizenship guarantees the right to cultural representation and the right to speak from one’s own identity. This right allows us to express ourselves collectively as part of a community without having to be completely integrated into it.

Political citizenship has proved important over the past two centuries, and economic citizenship emerged after the Second World War as a result of a need to guarantee the welfare state. Cultural citizenship, on the other hand, emerged after the postcolonial crisis and immigration from third-world counties to the western metropolises.

The first wave of migration in the mid-20th century to France and England included a postcolonial element, and was accepted with a certain degree of paternalism. The feelings of imperial guilt resulted in the need to adopt a rhetoric that welcomed the newcomers. The care shown by the British to Africans or Indians was not applied later to immigration brought by globalization from places like Poland or Latin America.

Interculturality needs to promote a real coexistence between different communities within the demographic diversity of each country, based on respect for a series of universal rights, and not on supposed attack of conscience of the old empires. Today’s migratory movements are the result of imbalances that go far beyond the old colonial constellations.