In her books, Najat El Hachmi, a writer of Moroccan origin, juxtaposes the world she comes from and the one she has found here, in a negotiation between both worlds. We are fortunate to have an author in Catalonia who has successfully been able to put this experience into writing.

Najat El Hachmi (1979) is one of the most celebrated and influential authors of her generation. Born in Morocco, she and her family moved to Vic, where she was educated in Catalan. In 2008 she won the Ramon Llull prize for L’últim patriarca [The Last Patriarch], a novel that brought this hitherto unknown world into Catalan literature. This year, she was recognised with the City of Barcelona award for her third novel, La filla estrangera [The Foreign Daughter], which had already won the BBVA Catalan Literature prize. El Hachmi’s mission is to write good books, although her excellent writing also manages to debunk clichés about Islam.

In La filla estrangera, there is an incident where the protagonist agrees to wear a veil purely due to the pressure from her family. With this novel, you make readers see that there is always a person behind the hijab.

Every woman who wears a veil does so for different reasons. For years, I tried to avoid the topic of the veil in my literary work or in the conferences I got invited to. The funny thing is to see how over all these years in which the media in the host society have been putting so much emphasis on headscarves, hijabs have taken on more meaning for the people who wear them. They have become symbolically charged; there has been a process of re-Islamisation that has been spread and reinforced from some countries which want to give a very specific vision of Islam and want to have a strong influence on the new generations of Muslims here. They don’t want to lose believers, because they know they will be able to dominate them politically that way.

And over here, there has often been a glaring inability to communicate with newcomers, to establish an authentic relationship. There has been a huge amount of condescension towards immigrants, which is seen very clearly in La filla estrangera.

We are used to thinking that the immigrants here don’t realise what we are saying about them; they’re talked about as if referring to an object, not someone who could be reading or watching you. When I was little and my mother wore a headscarf, I never questioned whether she had to wear one or not, but when everyone in Vic asks why you don’t take it off, you start to think that maybe the veil is important. The issue is even more complex in the case of Moroccan teenagers who live here, because there’s also the relationship with your body, the uneasiness that comes from sexuality and questions about what the right body is, because at home they tell you one thing and outside something completely different.

In La filla estrangera, you talk about a teenager’s sexual desire. You also explored feminine sexuality in La caçadora de cossos [The Body Hunter], which is a very different novel.

The topic of bodies is an issue that also affects western teenagers. How do you identify your desire and how do you channel it? What do you do with the desire your body can provoke?

You explore the relationship between sex and maternity both in La filla estrangera and in your articles. Sex links all areas of a person and is also linked to maternity; in your eyes, it’s not an independent entity. Said by a Catholic woman, this could be read as an fundamentalist statement. However, coming from the lips of a Moroccan who openly declares herself to be atheist, it has a totally different effect.

I talk about topics that unsettle me, but I don’t want to think that having a certain origin determines the way I talk about sexuality, which goes for the education I received at home as well. I reflect, and I do this based on the world I’m living in. I’ve been born in the age of contraception; for me it’s clear that sex and maternity aren’t linked…

So, you have to go further and understand what is happening in this sphere once the battle has been won to separate one from the other. I want to understand what’s happening to me as a woman, as someone who’s a mother as well. Linking sex and maternity isn’t taking a step back, but forward. I want to understand all the elements that make up the condition of woman and connect them. I don’t want to analyse it based on any ideological prejudice — as much as I may believe in feminism. The debate on maternity needs to be opened up.

You talked about maternity in a recent article, saying: “Human babies have the flaw of being born mid-gestation and it takes some time until they have the autonomy needed to detach themselves from their mother’s body”.

It was very difficult for me, it shocked me, despite having lived in an environment where breastfeeding was normal. It happened to me both with my first child and with my second. You realise you have to make a sacrifice out of love, as a bodily need, not because anyone has imposed it on you.

You describe a very interesting case in La filla estrangera, of a Moroccan mother who doesn’t want to take her small children to school because she needs to be with them, and the protagonist who acts as a social mediator is almost forced to wrench the child away from her…

There are many mothers — they don’t necessarily have to be Moroccan — who find themselves at this point. They are mothers who breastfeed longer than would be considered usual, who want to fully experience their maternity. And every day there is more aggression against mothers in the workplace, as if a woman who has had children cannot be as productive. According to some versions of feminism, the aim has been to ignore and deny this need for maternity, and the proposal is for us to have equal maternity and paternity leave. To me, seeking equality along these lines seems ridiculous; it is a paternalistic view towards women, promoted by precisely the versions of feminism that tell us: “They’re making you go back home…” I will never defend the professionalisation of maternity, because believe me, it’s not positive for the woman or her children. We have to be careful about the message we’re sending out. My daughter grabs the typewriter and says she’s a writer. You have to be able to experience the breastfeeding period with a certain peace without having to pay dearly in professional terms later on. I was afraid it would be hard to go back; in some professions it’s really hard not to pay dearly for it.

You’ve always defended feminism in your articles, up to the point of considering it one of the most significant changes in humanity. You’ve also written that “feminist children will not be born to us without doing anything, just because we have not experienced what our grandmothers experienced.” It’s not a case of machismo having returned, as is often said, it’s more the case that it never went away to start with. What role does feminism have today, and what pitfalls must be avoided?

We’ve sometimes tended to think about progress exclusively in terms of evolution, but ideology is not passed on through DNA, but through education and culture. That’s why we need to be aware of our mission as transmitters and not start sitting back and relaxing.

Feminism has sometimes been expressed in a purely rhetorical way. Isn’t the case of gender splitting something superficial? I’ve heard some real nonsense, like about the catalan teacher who addressed the students as “alumnes i alumnes”, so as to include both the masculine and feminine forms, despite them both being the same.

Splitting has almost no effect. It is much more significant to see how teenagers treat each other. We have to be very militant about basic things. Insults and mistreatment can never be permitted. It cannot be the case that in the public sphere they can insult you as a woman, that they can attack you for the body you have. On the other hand, from a feminist perspective, we cannot fall into temptation or mistakes we already made in the past, such as excessive political correctness or wanting to censor things.

Not long ago in Vic there was a controversy at a wedding fair. There was a photo of a couple where the bride was in an allegedly submissive position… and people from [leftist group] Capgirem Vic complained about it. I believe we can’t start censoring sexuality either; we can’t get involved in what kind of sex people should have. It seems like excessive correctness to me. It’s better to spend time on more important things, like inequality.

In terms of inequality, in a recent article you talked about the refugee crises and how we treat war refugees and economic refugees differently.

Yes, there are many people who are angry about what happens at the Greek or Hungarian border who would never call for immigration detention centres to be closed or demand more rights for the immigrants who are already here. It must be because class is more divisive than origin, and because in our minds we always look upwards when equating ourselves to others. Not long ago, the Duchess of Alba’s son was explaining that he had hosted a refugee in his home, and that they were a doctor… Obviously, the people who can get here are usually those with more money. And in some countries they have extorted that money.

You have had first-hand experience of immigrating. You went from Nador to Vic, from Vic to Granollers and finally to Barcelona. Have you felt welcome here?

Five years ago I came to live in Barcelona, a city I had loved for a long time through literature. For an immigrant family like mine, it was the city where we went to do paperwork, a place where we used to go to queue for hours. I became familiar with the places I’d learned about through reading, spots described by my top authors: Rodoreda, Montserrat Roig, etc., and Josep Pla as well. Places I’ve been emotionally involved with. So it was easier for me to put down roots in Barcelona, because even before it was a city I’d lived in, for me it was a city I’d read about.

It was a city I loved, but feared at the same time due to the anonymity it gives you, which can be positive, but it can also leave you without any protection. It’s a feeling that’s shared by many immigrants who live in regions outside the city and look at the city with respect, because as an immigrant, the place where you’re going is always very specific. You always go from one specific place to another, not from one county to another.

A small city like Vic may be more manageable, it allows you to form a network, but at the same time it conditions you, because you have limits. It’s interesting to see how, for many immigrants, especially for the children of immigrants, Barcelona is the city where you can actually stop being an immigrant. Once here, you separate yourself from your immigrant group, which gives you support when you need it but which also exercises social control.

You’ve worked as a cultural mediator, bringing the Moroccan and local communities closer together. In La filla estrangera, the protagonist’s mother says: “Moroccans’ worst problem is Moroccans themselves.”

Yes, this ruthless criticism is very typical of Moroccans. This sentence is also typical of someone who feels that the eyes of others are on the group itself, because the host society has the need to identify a group and label it.

When I was working as a mediator and would act as an interpreter, some women would ask me not to translate everything they said: “Don’t translate this,” they’d say to me with a certain foresight. It was the awareness of belonging to a group without power within another larger group, the awareness of living without equal conditions. When we were little my parents would tell us: “This isn’t our land”.

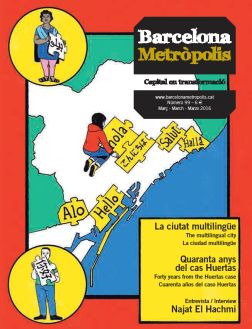

In this issue of Barcelona Metròpolis we look at the topic of multilingualism in the city. And now that you mention your experience as a mediator, what’s it like to be an author who speaks different languages with her parents, siblings or children? How do you think linguistic diversity should be addressed? The Grup d’Estudi de Llengües Amenaçades [Threatened Languages Study Group] says there are 300 languages spoken in Barcelona, and proposed a vote to decide which one should have the honour of taking this number.

I would vote for a pidgin language, a creole language. My nephews live in Vic in a neighbourhood where there are lots of Berbers, and the way they mix Catalan and Tamazight is amazing. They take Catalan verbs and inflect them in Tamazight. The Tamazight they speak has interferences from Vic Catalan now. And there are also Tamazight elements in the Catalan they speak to each other.

What languages do you speak with your family?

When I was little, I lived in an outlying district of Vic and went to public school. I remember having to learn Spanish on the playground, after learning Catalan in the classroom, because if we didn’t speak Spanish, the other kids would make fun of us. So I ended up speaking in Spanish with my siblings. Then most of us ended up speaking in Catalan or Tamazight with our children. I speak Tamazight with my mother, Spanish with my siblings and Catalan with my children. The sociolinguistic factors change over time; there are no clear and defined patterns, but rather it happens like this.

In terms of the present and future of the novel, you’ve said that writers shouldn’t feel forced to innovate at every turn. Maybe now we’ve reached the end of the history of the novel and can finally talk about what’s important. You’ve also recognised the debt to the women in your family, great storytellers who knew how to explain things, lingering over details and creating dramatic tension. What kind of influence has Moroccan women’s storytelling style had on your work?

To be fair, I’d say that it can’t be considered a trait of Moroccan women. It’s more one of my mother’s gifts, which fascinates me. My mother is illiterate, but she has a unique ability to tell stories. She starts talking and you immediately find yourself inside her story; I don’t really know how she does it. She does it naturally, without hesitating, with an ability to capture detail. I remember being silent, listening… An influence like that isn’t recognised anywhere, nor is it honoured, but there are my roots as a storyteller. My great-grandmother was a great storyteller as well, with great vitality, and she had this same instinct for telling stories. I can only hope to be able to explain this disappearing world through literature.