A neighbourhood meeting descended from the 15M movement, in the Plaça de la Vila in Gràcia.

Photo: Dani Codina

Barcelona is experiencing a blossoming of group initiatives and citizen selfmanagement. This begs the question of whether these initiatives are replacing the obligations of the public administration. A barrier against inequality can only be built if the public administration takes its role seriously and helps to construct a dialogue with an organised citizenry.

In October 2015, the University of St Andrews in Scotland published the report Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities, which recognised a widening gap between the rich and poor in eleven of the thirteen most mportant European cities between 2001 and 2011, which it claims could be “disastrous” for social stability. It does not mention Barcelona, but reveals Madrid to be the city where inequality grew the most over the ten-year period. The study identified four pillars which prop up what it refers to as segregation: globalisation, inequality, the restructuring of the labour market and property speculation.

All four of these pillars are currently prominent in Barcelona. In fact, one of the first measures approved by the new municipal government, just one month after taking office at the City Council, was to assign 2.5 – 4 million euros to an additional child benefit payment for vulnerable families. In 2013, the Federation of Organisations for the Care and Education of Children and Adolescents (Fedaia) reported that 25% of children in Barcelona are living on the verge of poverty. How did it come to this? What is more, the

outlook continues to worsen. On 20 October 2015, Agustí Colom, the councillor for Employment, Business and Tourism, published a report revealing an increase of lowincome households from 21% in 2007 to 41.8% in 2013, while the proportion of people on middle incomes fell 14.3% to 44.3% over the same period. In other words, the crisis is increasing the number of people on low incomes and reducing the proportion of middle-income households, or, to put it another way, those with work are getting poorer and inequality is increasing.

From outrage to protest and mobilisation

Tourist Barcelona and social marginalization are evident in this picture, taken on the Rambla del Raval.

Photo: Dani Codina

The year in which the academics who conducted the European study concluded the fieldwork for their report was the same year in which Barcelonians began to vent their anger. In March 2011, Stéphane Hessel visited the city to present Time for Outrage!, a brief but conclusive book that acted as a trigger for many young (and not so young) people to start to see the crisis as the business of a financial system that rewarded profit regardless of the means and which funded political corruption so that nothing would stand in the way of business. Also in March, Ada Colau, the current mayor of Barcelona, answered questions about the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages (PAH) in the dining room of her home, with a blue plastic curtain acting as the door to her kitchen. Colau was an activist for a movement that was gaining momentum, which has arguably become the most important movement in 21st-century Spain. In her home, Colau warned: “One day, thousands of people that are building local alternatives may occupy the streets”.

From 15 May 2011, people started to occupy the squares: the Plaça de Catalunya in Barcelona, the Puerta del Sol in Madrid… It was in these squares that some of the answers and actions to address the problems of globalisation, inequality, the restructuring of the labour market and property speculation were first formulated, in what was known as the 15M Movement.

A protest in favour of public education and against the policies of Minister Wert, in October 2013.

Photo: Dani Codina

Ancor Mesa Méndez, in 2011 a Social Psychology PhD student at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), has lost count of the number of times he crossed the Plaça de Catalunya during this occupation. He had become fully engaged in association activities one year previously, as a consultant for the Federation of Neighbourhood Associations of Barcelona (FAVB) where he still works, and the 15M Movement struck a chord with his twenty-something mentality. During those days and nights in May, Ancor, like many of his fellow citizens, began to wonder about these collective, cooperative, self-managed and horizontal movements that suddenly emerged as a response to globalisation, the restructuring of the labour market and property speculation – all pillars of the St Andrews report. Inequality had yet to make an impact on public discourse in Spain. What is more, in 2011 the Partido Popular (People’s Party) abolished the teaching of Education for Citizenship, replacing it with a study of the world’s conflicts.

A PAH demonstration against evictions in February of the same year.

Photo: Dani Codina

Ancor, who was born in Tenerife, had never experienced anything like a neighbourhood group. In Barcelona, working on his thesis and living in temporary accommodation (due to the price of rent, belonging to a generation at risk and as a consequence of living in a city defined by its demographic mobility), he also failed to lay down roots in any particular neighbourhood. This occupation, this “conclave without boundaries of free people coming from different places”, as Ancor defined the 15M Movement, really spurred him into action. “I began to wonder how to use all the energy that was being pooled to formulate collective policies daily at a grass roots level from the neighbourhoods”, he recalls from the FAVB meeting room situated behind the Plaça Reial, in what today is a valuable library of books on popular and neighbourhood struggles of the seventies and eighties, which fought for and won cultural centres, schools, public transportation and hospitals.

A sleep-in at the Hospital Clínic in December 2012 against austerity measures and the privatization of the health system.

Photo: Dani Codina

The role of neighbourhood associations

“No-one was better at challenging the way daily politics are conducted in the aftermath of the 15M Movement than the neighbourhood associations”, maintains Ancor, who is currently the sociological leader of the Barri Espai de Convivència programme, an analysis of Barcelona’s neighbourhoods compiled with the participation of all the neighbourhood movements. According to Ancor, this research project came about because “the groups see themselves as agents for their environment, with an open-minded and collective approach to problems”.

“Pren els barris” [Take the neighbourhoods] was the slogan under which the camps in the squares were gradually dispersed. Sants, El Raval, Gràcia, Fort Pienc, Barceloneta, Horta, Nou Barris… they were all covered with posters announcing “popular assemblies”. The year 2011 laid the foundation for the following years: 2012, the year of deprivation; 2013, the year of protests against the cuts and austerity and of the democratisation of poverty; 2014, the year when even in Davos talk turned to the need to reshape capitalism.

Firstly, in 2011, the major debates surrounding inequality in Barcelona were hitting the headlines: settlements, evictions, reform of Guaranteed Minimum Income benefits, childhood poverty and impoverishment of working people. IDESCAT (The Statistical Institute of Catalonia) reported that 1.5 million Catalans were living in poverty, one million of which in the province of Barcelona.

Furthermore, the City Council itself reported that, since 2008, all districts with a household income greater than the city average had seen their wealth increase, whereas earnings fell in districts with a household income below the average.

“Iaioflautes” banners in a protest for healthcare, education and housing in May 2012.

Photo: Dani Codina

Various groups have taken to the streets dozens of times over the last four years in what have been called “waves”: health groups protesting against cuts to healthcare (white T-shirts), education groups (yellow T-shirts), cultural groups (red T-shirts) and social services groups (orange Tshirts). Neighbourhood residents, as well as people affected by the same common problem, joined the groups and took the demonstrations to the squares and the streets. This led to the foundation of the Nou Barris Cabrejada campaign, which brought together multiple disparate entities from the district: Apropem-nos, Quart Món, the “iaioflautes” (a civil rights group comprised mainly of the older generation), residents protesting against the abolition of the Dependency Law and cuts to the Guaranteed Minimum Income. In the Plaça de Sant Jaume, no sooner had one demonstration ended than another would begin.

Cooperative movements that empower

The financial services cooperative Coop57.

Photo: Dani Codina

Secondly, 2011 saw the birth of a citizens’ empowerment movement that turned Barcelona into an urban laboratory of cooperative groups and self-management. This represented another step away from the classic dichotomies between state and public and private and commercial, with the public revealed to be the common element.

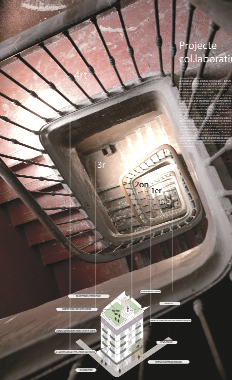

The Observatori Metropolità de Barcelona (a Barcelonabased research group) recorded fifty self-managed initiatives across the city’s neighbourhoods in its Comuns urbans a Barcelona study. According to the study, “At a time of cuts to public services and welfare and a curtailing of rights, we wanted to see what kind of city model is being envisaged by community management practices”. The name if its website leaves no room for doubt about its nonconformist nature: Stupid city, an ironic name for a project to study a city built on collective intelligence, juxtaposed against the smart city, which, in their eyes, excludes many of its residents.

Germanetes community space, managed by the Eixample Neighbourhood Association and Recreant Cruïlles. This is one of the projects that already work as part of the initiative driven by the City Council to give a social and community function to unused municipal lots.

Photo: Dani Codina

These cooperative, self-managed or citizen-led movements concern themselves with such issues as energy (Som Energia), local ownership of public spaces (Germanetes in the Esquerra de l’Eixample neighbourhood, the Plaça de la Farigola in Vallcarca or the Pou de la Figuera in El Born), health (the Espai de l’Immigrant), telecommunications (Guifi.net), housing (buildings occupied by the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages, or the La Borda squat in Can Batlló), public amenities (the former factory, Can Batlló, and the Ateneu de Nou Barris), care and finances.

Coop57 defines itself as a “cooperative of ethical and solidarity-based financial services”, a para-banking entity independent of the Bank of Spain that invests the savings of its members into social projects, whether they be local associations, cooperative housing projects or cultural foundations, etc. Guillem Fernàndez, of the credit department, lists the requirements that an organisation has to meet to be approved for Coop57 funding, which sound like the Ten Commandments of the Indignados movement. “Projects must comply with social principles, have their roots in the area, have a highly-developed collective network, and with the difference between the lowest and the highest wages not exceeding a ratio of 1:2”.

The fact that this in no ordinary financial institution leaps out at you as soon as you arrive at their branch in the Carrer de Premià, in the Sants neighbourhood. There are no screened glass counters, no queue number machine, and employees are not dressed in suit and tie. Their philosophy is assembly-based with a flat, commission-based organisational structure; principles that it shares with most 15Minspired movements.

Germanetes community space, managed by the Eixample Neighbourhood Association and Recreant Cruïlles. This is one of the projects that already work as part of the initiative driven by the City Council to give a social and community function to unused municipal lots.

Photo: Dani Codina

For Coop57, founded by employees of the dissolved publishing house Bruguera, the camps of 2011 were not the beginning, but rather the peak of activity. Savers fed up with evictions and disgusted by the preference share institutions that took their savings to other types of financial institutions flocked to Coop57, just as they did in 2003 during the Iraq war protests. Throughout the seven years of economic crisis, Coop57 has designated more than 43 million euros to social economy and solidarity projects in 1,160 transactions.

Fernàndez claims that the initiatives and entities that have recently been coming to Coop57 relate to the dismantling of the welfare state. He lists educational, housing, health and food-related initiatives. “To what extent should we fund projects if they continue to pick up the slack in spheres that State doesn’t enter, or end up undoing what remains of the welfare state?”, he asks.

He is not the only one. To what extent are citizen-led movements replacing the State in the fulfilment of its obligations? This is the question that began to resonate in 2015. “

What do you need public services for?”

The anthropologist Manuel Delgado is extremely critical of the space occupied by these initiatives. “If I were the State, I would ask: what do you need public services for if you believe so much in community initiatives?” This is a real sticking point for him. He has no doubt that all these selfmanaged initiatives allow society to function without the support of the State, and that they become a kind of substitute that neglects to complain, in the form of social struggles, to the Public Administration that it should be a “truly public” state. Is there any other way? “Decisive and clear actions, for example, concerning housing”, he proposes. “It’s complicated because it basically means doing the opposite of what we have always done until now: selling land, instead of buying it. And the same goes for fuel poverty”.

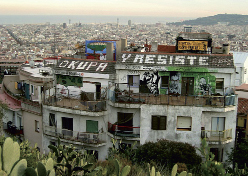

According to the PAH, in 2015 there are still 22 evictions every week in Barcelona and housing continues to be an unresolved issue in the city. There are 2,591 bank-owned apartments that have stood empty for more than 24 months. Only 2% of housing stock is social housing. In October, the City Council gave an ultimatum to the Company for the Management of Assets proceeding from the Restructuring of the Banking System (Sareb): either Sareb releases 562 empty apartments for social housing, as required by law, or the City Council would take them to court. The transfer of empty flats is provided for by article 7 of the law approved this year by Parliament pursuant to the Popular Legislative Initiative (ILP) pushed through by the PAH and the Alliance against Fuel Poverty.

A few weeks ago, the SomAtents newspaper group published a debate on Housing, in which numerous social parties with an interest in housing in Barcelona were invited to take part. The debate took place in the Plaça de Joan Corrades, in Sants, opposite a building occupied by the PAH. The meeting went on for more than an hour beyond its end time and was opened with the following words from Josep Maria Montaner, Councillor for Housing for the Barcelona City Council and representative of the Sant Martí district: “After unpaid labour, the second element of public control inflicted by capitalism is the difficulty of accessing housing. We believe that over the next four years we can improve housing conditions in Barcelona: by tackling the housing crisis; by ensuring that empty apartments are made available for social use; by building new housing as sustainably and as fairly as possible; and by initiating a regeneration programme as part of neighbourhood improvement schemes. Innovation lies at the heart of our proposal, based in particular on new ways of life and new forms of ownership”.

Alternative ways of living

The Can Batlló space, in the Bordeta neighbourhood, has been waiting to be renovated since 1976, when it was set apart for public facilities, social housing and green space. In 2011, the neighbours initiated an experiment in self-management in part of the space, which they dedicated to social and cultural activities. Social housing promoted by the La Borda cooperative is also planned for this space.

Photo: Dani Codina

Are there alternative ways of living in Barcelona? Carles Baiges is an architect and a member of the LaCol architects cooperative. He graduated from the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC) with the understanding that architecture is a form of social action/intervention, and since 2014 has been one of the sixty cooperative members of La Borda, the cooperative that provides housing under a cession of use scheme to be established in Can Batlló.

It works as follows: the City Council relinquishes the property for 75 years and the asset is collectively owned by the cooperative legal entity. Each household (so-called “cohabitation unit”) invests 15,000 euros as share capital of the cooperative, and subsequently pays a membership fee below the market price: 450 euros on average and 500-600 euros for large apartments. Alternative funding for the estimated 2.4 million euro construction will be provided by the Coop57 cooperative. La Borda is following in the footsteps of the Danish model, established a century ago, and the Uruguayan Federation of Mutual Aid Housing Cooperatives. In Denmark the model has been so successful that in Copenhagen alone there are 125,000 homes in the cooperative. As Carles Baiges explains, the initiative started from the grass roots level, by an organised citizens’ group looking for alternatives to the housing model. He talks about self-builds, about “living, not speculating”, about communal areas, getting to know your neighbour, the connection between the “cohabitation units” and Sants, and of course of the “replicability” of the model. “Like most young people in Spain, my financial situation is fairly uncertain and it is difficult to find adequate housing, but we also have the will to change the ownership model”, he declares. “I don’t want to move to the countryside and I believe that we can live more communally in the city. The apartments could be smaller than average, but the idea is that the people live in the communal areas”.

Did the 15M Movement influence the way the city and society are envisaged? “There are many of us who believe that the entire Can Batlló movement was greatly influenced by the events of 15 May, including the brutal removal of people. Rather than in the so-called new politics, I’m seeing the ‘They do not represent us’ concept in all the movements that progress from protest to action. They may not have come together as a group at the time, but they proved that they could do something. In my opinion, the legacy left behind is the realisation that we had the tools and the ability to do something”.

On 24 May 2011, just three days before the violent eviction from the Plaça de Catalunya, the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano (died April 2015) wandered through the square. It was night time and his presence went unnoticed. A young person recognised him and in what he calls a chat, but what in reality became an 11-minute monologue, Galeano reflected into a camera, perhaps a mobile phone: “This is a crappy world which is pregnant with another”. This other world is happening behind the camera. Sometimes he looks at it out of the corner of his eye, sometimes the others look at him. There are young people with sleeping bags who have spent days shouting and arguing that politicians do not represent them, there are yellow T-shirts bearing the slogan “Take the street” on the front and there are green PAH T-shirts. Just before he finishes, he reflects: “I’m often asked what will happen and what will become of this afterwards. And I simply answer that I do not know what will happen, nor do I care; they only thing I care about is what is happening now”.

Access to health

The Espai de l’Immigrant on Passatge de Bernardí Martorell in the Raval.

Photo: Dani Codina

The Ciutat Vella neighbourhood completely reflects the four pillars referred to in the Saint Andrews study: a globalised neighbourhood, rife with inequality, with mafias that speculate with property and gentrified to the last cobblestone. For years, the Passatge de Bernardí Martorell has been excluded from El Raval’s popular streets and thoroughfares, despite the bar and the phone booth business, and despite the fact that it is actually not that different from any other street. The Espai de l’Immigrant [Immigrants’ Space] is located on this street. A group of healthcare professionals came together to oppose the approval of decree 16/2012, which would limit and restrict access to healthcare and leave 873,000 people without medical care due to irregularities in their administrative status. There is an old hotel on this street which is now a social centre and home to the Espai. For the last two years, whether in El Raval’s Carrer de l’Hospital or Carrer del Carme, you can always find people asking where the Passatge de Bernardí Martorell is.

The Espai de l’Immigrant on Passatge de Bernardí Martorell in the Raval.

Photo: Dani Codina

Doctors attend on Fridays and lawyers on Wednesdays, at the same time that the collective’s weekly meeting is held in the apartment’s kitchen-dining room. The living room is almost a conventional waiting room. There is a landscape picture on the wall, chairs, people waiting with mobile phones, and a voice that calls them up. But the walls are fuchsia-coloured, the air is not close as there is a balcony overlooking the street, and the people speak loudly. The vocabulary employed in the waiting room can be recognised as the language of outrage and protest: colonialism, classism and integration; there is talk of a documentary film festival.

It is Friday and the doctors are there, but they do not wear white lab coats, prescribe medication or ask for health insurance cards. They are volunteer doctors who, together with social workers, psychologists and lawyers, inform immigrants not in possession of the correct documentation of their rights and assist them in applying for a health insurance card – a process that can take days or weeks due to the language barrier and an ignorance of the bureaucratic system. “They often won’t see immigrants who come on their own, but will help immigrants who are accompanied by a Spaniard in a position of authority, which is borderline racism”, complains Estefanía, a doctor. Accompanying an immigrant means carrying a copy of the law with you, going to the Primary Care Centre (CAP) and sometimes arguing with the official behind the desk.

They say that this is the “most punk” activity undertaken by Espai de l’Immigrant. “We are not trying to fill a gap that the State should be filling; we are simply providing users with the tools to access the public health system to which they are entitled as registered residents”, explains Elvira, resident doctor at Hospital Vall d’Hebron and volunteer at the Espai de l’Immigrant.

The Espai de l’Immigrant on Passatge de Bernardí Martorell in the Raval.

Photo: Dani Codina

María (this and the names that follow are not their real names) lives in El Raval and found out about Espai in the same way that most people do: by word of mouth. The socalled Thursday Street Brigade roam the streets of Raval every week to ensure that word gets around, but they still complain that most people only attend after their situation has become serious. That is how María came to be there. She had known about its existence for months, but she only came because she had a broken thumb. She didn’t come because of the pain of the fracture, but because she did not have a blue health insurance card and because she could not pay the “more than 200 euros” that A&E charge for an X-ray and the placement of a splint. The doctors had to explain syllable by syllable that A&E “do not charge”.

At Espai de l’Immigrant they told María that she was entitled to a health insurance card because she is registered. Nobody had told her that before. “Most politicians will tell you that healthcare is for everyone and that they will treat everybody. And by law this is true, but there is a lack of information directed at migrants and foreign citizens about how to access it. This information is completely useless unless the Government invests money and introduces new policies to disseminate the information to the people that most need it”, points out Elvira.

The Espai de l’Immigrant is working to recover María’s 200 euro payment: the lawyers meet every Wednesday.

Three Barcelonas

The three faces of Barcelona can be seen on the corner of the Passatge de Bernardí Martorell 7 days a week. The fourstar Rambla del Raval hotel, the homeless community that meet in the basement of the Comisiones Obreras trade union (there are an estimated 3,000 homeless people sleeping rough) and the constant flux of people with insecure employment: the unemployed, those in temporary work, people with a cart full of scrap in tow. Ciutat Vella has accommodated many of the young people who used to live in the abandoned factories of Poblenou; they now live in empty apartments on shady streets.

The courtyard of the School of Geography and History on Carrer Montalegre, where many actions against social segregation have taken place.

Photo: Dani Codina

In October, Councillor Colom pointed out that Barcelona’s unemployment rate is 13.9%, rising to 27% among young people. 53% per cent of unemployed people are over 45 years of age and 44% have been jobless for more than a year, with unequal distribution throughout the city and some districts experiencing double the unemployment. The Sarrià-Sant Gervasi, Eixample, Les Corts and Gràcia districts all enjoy below-average unemployment, whereas Sants-Montjuïc, Horta-Guinardó, Sant Martí, Sant Andreu, Nou Barris and Ciutat Vella are above the average.

Joan Uribe has just arrived from Argentina. Together with 24 other experts, he has been discussing the homelessness situation at the International Gathering on Homelessness and Human Rights. On his Twitter feed, words such as gentrification, exclusion, entitlement to the city and to the street, and the homeless are in every other tweet. He is the Director of Social Services at Sant Joan de Déu Hospital and teaches at the Faculty of Geography and History of the University of Barcelona (UB).

In the notebook there is a vital question to help understand the upcoming years: Will the future be collaboration between associations and the State? “I’m delighted that you forgot the market”, he replies. “A positive vision of the future would be if social movements, organisations and associations were to work together with the State. There would certainly be friction, but it could be possible to come together to construct a barrier to counteract the logic of the market, thereby building better societies than we have today, at the very least achieving the minimum level that we had a few years ago, and perhaps even going further”.

Can you give an example of these barriers? “In Latin America, some groups started working together to fight for the right to land, housing and the city. After twenty, thirty or forty years, they have not only succeeded in changing the legal framework, but they are also represented in the very forums of decision-making on public policies. In Finland, collaboration between associations and the administration has brought an end to the phenomenon of homelessness”.

Outside the Faculty of Geography and History and opposite Barcelona’s Centre of Contemporary Culture (CCCB) is an information panel about the dozens of talks which, in their different ways, are helping to lay the foundations of this barrier. There is a shared vocabulary: selfmanagement, ethical finance, responsible consumption, cooperative movements, housing and, of course, the big enemy to defeat, social segregation with its four pillars: globalisation, inequality, the restructuring of the labour market and property speculation.