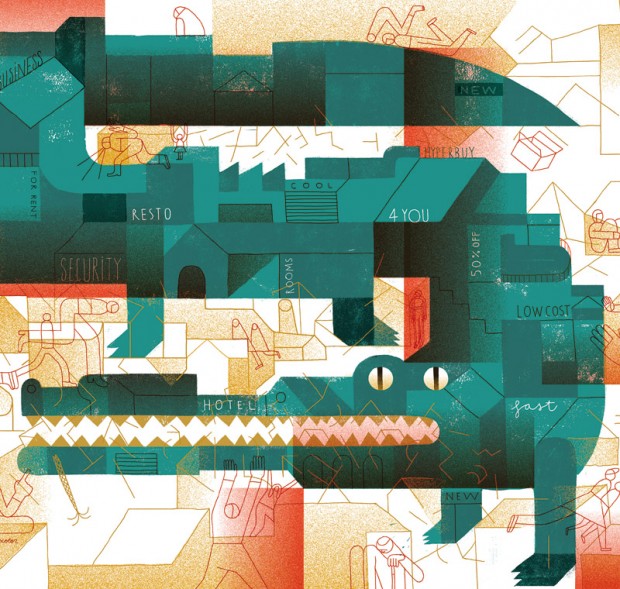

The Heliogàbal cultural association, in Gràcia, which has specialised almost entirely in poetry recitals for several months.

Photo: Dani Codina

The city grows after eight, but haphazardly and, according to many critical voices, under the orders of tourism. It wasn’t planned for the night, unlike what other European cities have done. It’s overflowing with musicians and venues anxious to schedule live concerts, but years of applying a policy of restrictions has sunk the sector in depression.

The City Hall approved a new set of regulations months ago to allow bars, cafés and restaurants to schedule live amplified music so long as they abide by security requirements and strict noise control. This is a foretaste of an ambitious plan to promote the small-format live music scene, based on recognition of the cultural and social value of this leisure offer. Live music is a grassroots cultural manifestation with a long tradition among us and backing it has to do with the model of city.

Chink-chink. That’s the metallic sound made by coins when someone is fiddling with them, counting them, dishing them out. Plink-plink. There are also some €5 notes in there and one or two €10 notes. Most of it, though, is loose change. The band, Pol Omedes Special 4tet, has just finished a gig – some jazz classics and a couple of their own compositions – and now they’re getting paid, mainly from the proceeds of a collection tin, although the owner of the bar has also chipped in. The amount is not even sufficient for an “ethical” daily wage. The bit about ethical is mentioned by Albert Pons, part-owner of Robadors 23, where the quartet have just been playing.

Barcelona comes alive just after 8 pm, but, critical voices say, without any kind of planning and at the bidding of tourism. Nightlife has not been thought about like it has in other European cities. Barcelona is full of musicians and venues that are keen to have live music, but the restrictions introduced by the tripartite left-wing local government and developed during the term of the CiU, the Catalan nationalist party, have caused a real downturn in the city. The current government team has warned that the scene “is at risk” and, to save it, it has introduced a new legal framework that modifies the approach to how nightlife is managed. It is a significant change: bars, restaurants and cafes that couldn’t legally put on amplified live music in the past without being fined, can now do so provided that they don’t exceed a certain volume of decibels, which varies depending on the area, and that they meet safety requirements. The measure is intended to boost the small-scale live music circuit, one of the most popular expressions of culture in the city.

In the blink of an eye, Barcelona went from the creative frenzy of the seventies – with a psychedelic, hippie vibe concentrated in venues like Zeleste – to the recklessness and noise of the late eighties. Pre-Olympic Barcelona’s nightlife was utter chaos: punks, hippies and party animals crowded all corners of the city.

The chaos of the eighties and nineties has now been reduced to a literary myth and yet, somewhat contradictorily, still forms part of the brand: sold even though it doesn’t exist. Mexican author, Sergio Pitol, described that Barcelona live from Carrer dels Escudellers in his book Diario de Escudellers (Diary of Escudellers). In 2016, Barcelonian writer Miqui Otero turned nineties Barcelona into the novel Rayos (Rays). Fidel, Justo, Iu and Brais – the main characters in Rayos – spent their wild youth in Barcelona during the early nineties: they said goodbye to one city and saw another one born.

From chaos to branding, and from branding to depression

Pasqual Maragall’s socialist government laid the foundations for the Barcelona brand. Little by little the city was transformed: it went from being the equivalent of a student flat overflowing with cigarette butts, music blaring until all hours and anarchic breakfasts, to a guest house for 12 million tourists looking for the Barcelona of the brochures and largely focused in Port Vell and Port Olímpic, areas that have become tourist hotspots for fighting and binge drinking over the past few years. Despite repeated complaints from the residents of Vila Olímpica, no solutions were forthcoming until last summer, when Barcelona City Council agreed to sign a protocol with the Catalan Regional Government to take on ownership and direct management of Port Olímpic, a measure that will come into effect from 2020, when the current licence expires.

Barcelona’s music scene was becoming a depressed reality, marked by an invasive tourist model that undervalued and impoverished small venues. What’s more, nightlife became an integral part of this model.

Performance at the Absenta bar in Ciutat Vella, Carrer de Sant Carles.

Photo: Dani Codina

New legislation full of promise

The current local government took office in Barcelona in May 2015 with a policy programme that included efforts to address the predicament facing music venues. The Culture Institute of Barcelona (ICUB) set itself the task to develop a Plan about music, in coordination with other departments and all the districts.

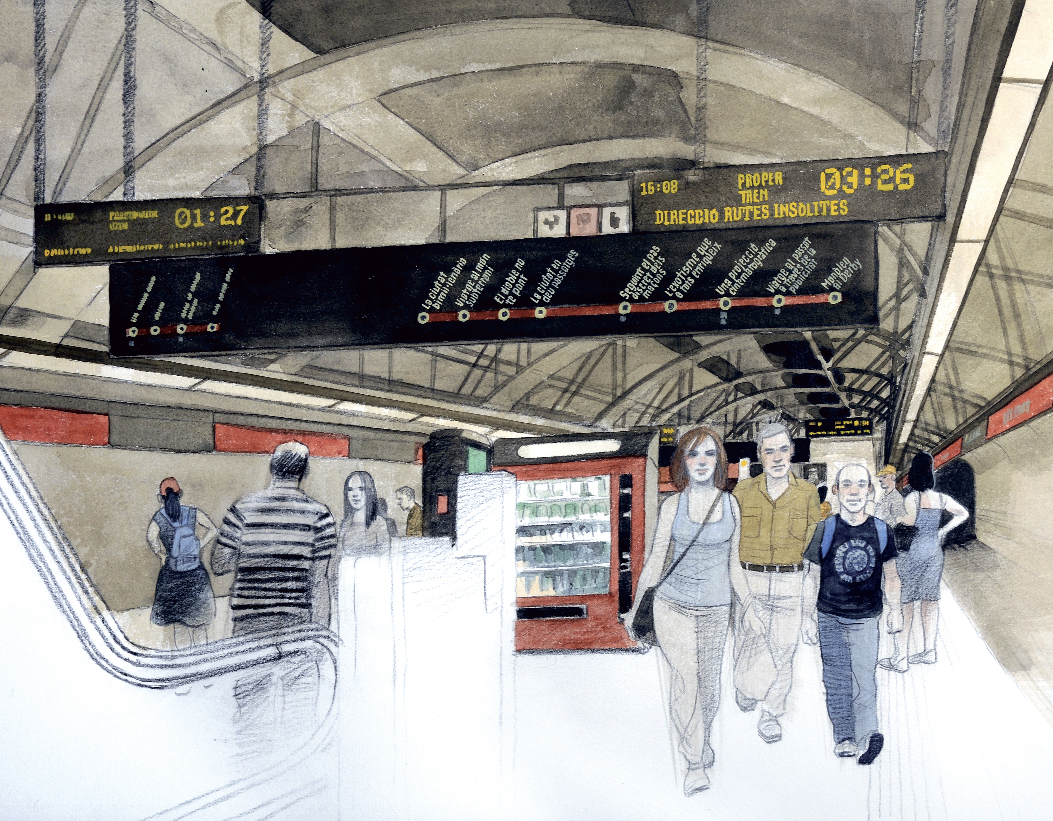

The plan focuses “on different areas of activity to foster recognition of the cultural and social value of live music, while also taking into account its sustainability in terms of neighbourly relations that guarantee the right to sleep” for residents in las áreas próximas a los locales. The set of measures put forward for live music forms part of the Culture Plan 2016-2026, which aims to redefine the relationship with the city’s cultural sector over the next ten years and it was the cultural proposal that received the most votes in the Decidim Barcelona (We Decide Barcelona) participatory process that forms part of the Municipal Action Plan 2016-2019.

Before making public the plan, on May 11 the ICUB published a circular to regulate the performance of amplified live music in hotel establishments. To the new regulation can be hosted premises like Robadors 23 and Absenta bar, which, until its approval, were technically staging illegal performances. From the outset, it was well received by musicians, bars and restaurant owners, who will also be able to benefit from subsidies: a total of €400,000 has been set aside so that premises can be adapted to meet the new soundproofing requirements. It’s a breath of fresh air for an industry that – while not yet losing its scepticism – is viewing it as an opportunity to rebuild the musical nightlife scene as a space and a time with huge potential for civic social integration. Another positive aspect is the opportunity it provides to fill the gap between the two extremes that, until now, have been the only options on offer for musicians in Barcelona: playing acoustic, or “unplugged”, in a bar or playing amplified in a bigger venue.

Musical performance at the Robadors 23 bar, Carrer d’en Robador, Ciutat Vella.

Photo: Dani Codina

Robadors 23 as a symbol and symptom of the music scene

As the applause dies down, people are heading out the door of Robadors 23, and, with them, the members of the Pol Omedes Special 4tet: they are chatting, smoking and laughing in the street in El Raval district. The end of the performance coincides with the shops closing and with cinema-goers passing by on their way to see the night’s final showing (9.30 pm) at the Filmoteca de Catalunya, a local cinema.

The Pol Omedes Special 4tet, – trumpeter, saxophonist, double bassist and drummer – each get a share of the proceeds from the collection. The entry price was €5, and there were around 30 people in the audience. So how much did they collect in the end? “I’m ashamed to admit it, but the pleasure of performing a particular type of music, in the company of a particular group of musicians, compensates for the meagre income we make. I feel bad saying it, because I have a lot of respect for Robadors 23”, says Martin Leiton, the double bassist. He is from the Canary Islands and, despite a precarious work environment, he has chosen to settle in Barcelona and to make his living by making music. He used to play in Malaga, Cuba, Buenos Aires, Madrid and in his homeland of Tenerife.

“On a normal day like today there are usually around 30 people. We could put our prices up, but then we’d only attract foreigners. And if we didn’t put gigs on at all, nobody would come”, laments Albert Pons, one of the part-owners of Robadors 23. The venue’s own history embodies the contradictions of the city’s night-time music scene.

Robadors 23 opened in 2004, when the street was not much more than a passageway full of used condoms and discarded single use needles. Now, there are cool bars, and the Barceló Raval Hotel, which offers rooms for up to €300 a night, is just a stone’s throw away. Since 2004, Robadors 23 has been closed on three occasions for “police and urban issues”, and has reopened the same number of times. The venue was almost closed down for a fourth time at the start of 2016, but the current legislation “saved them by the skin of their teeth”, Pons explains while sat at the very bar he tends during the dozens of performances the bar hosts each week. Another performance is due to start shortly: this time, it’s flamenco. Robadors 23, which has become one of the cult bars for musicians passing through the city, is one of the bars that appears in tourist guides as representing the Barcelona night.

The saxophonist opens his wallet and starts putting his money away. He’s Lluc Casares and he is one of the young Barcelonians that the city has driven out in the name of new inspiration and opportunities. That’s how he justifies his move to Amsterdam: “There, I make a living off my music, but I admit that we are a generation that is not used to earning money. Our lives mean going to play in these places, enjoying them and surviving however we can.”

Destiny took Lluc Casares to the Netherlands almost five years ago, but if any “little things” happen here in Barcelona, he gets a low-cost flight back. He graduated from the Catalonia School of Music (ESMUC), and followed that up with a Master’s degree in Amsterdam and an exchange programme in Philadelphia. So far, his musical career can be summarised by this triad: scholarships, “a lot of inspiration from other musicians” and performances in small venues. He does also play in large venues, but they are an exception. Casares is convinced that Barcelona is an “inspirational” city, but he also thinks that it is difficult to show the fruits of this inspiration: there are many musicians in competition between them and there are few opportunities to play live properly.

A change of model

The conditions under which venues offer live music was a source of intense debate in the days following the last local elections, a debate that has now been fully introduced into the political decision-making sphere. The issue is not only about fines or the conflict between residents and bar owners, but also its effect on the city’s model for leisure activities and the city’s model in and of itself. Betting on live music is one way of supporting grassroots cultural events: and that is where small venues and local bands come in.

Carmen Zapata is one of the names heard that night, one that is still defining her course and what it means to be Barcelonian. She is the manager of the Catalan Association of Concert Venues (ASACC) and founder of the Association of Women in the Music Industry (MIM). She was interviewed on Scannerfm, the first radio station to broadcast solely online in Barcelona. Zapata shared the sofa with Miquel Cabal, general manager of Heliogàbal, the Gràcia venue that had to shut down before the summer, besieged by police inspections and facing regular fines. It had managed for 20 years on a licence that did not meet its needs as a live music venue.

“We continue living in a state of alarming insecurity, and it does not look as though there is any way to resolve it easily or quickly”, Zapata replies to a question from the Scannerfm interviewer. “Although there is a will, which helps, it is much easier to change things when there is a political will. But it is the Catalan Regional Government’s Department of the Interior, the body responsible for regulating shows and concert venues, that needs to show both political will and cultural sensitivity. And that is where we come up against the police.”

Some 30 venues are part of the ASACC. Carmen Zapata explains that the entity, created in 2001, is continuing to call for conflicts with venues to be managed from a cultural perspective and for the responsibility for resolving problems on the streets to fall not the owners. “If someone shouts in the street, the owner should not be held responsible. Venues are already tasked with making certain reinforcements”, she says.

The musician, researcher and cultural producer Daniel Granados, programming director of the meeting Cultura Viva, of the research platform ZZZINC and of Producciones Doradas, advises the ICUB on matters of music policy. He has spent years insisting that a city should rethink what is meant by music and by cultural expression. From there, he thinks that a city should recognise and promote grassroots culture and protect whoever wants to grab a guitar in a bar just because they can, as well as anyone who wants to make a living from doing just that. Granados took part in developing the legislation for amplified music as well as participating in the already mentioned Culture Plan 2016-2026, that municipal governments present when they start their term.

Absenta bar, in Plaça del Pes de la Palla, regularly schedules live music in its basement. With the new legislation, it can do so legally. The bar is practically deserted; the only noise is background music, at a volume that is just slightly louder than silence, and the conversations at a couple of occupied tables. White noise, is what Daniel Granados calls it.

The serious problems come from the streets

La Rouge music bar, on the Rambla del Raval, at night.

Photo: Dani Codina

The new legislation rigorously safeguards the health of residents from noise pollution, particularly in the Ciutat Vella, Sants, Gràcia and Eixample districts, where “critical levels of overcrowding in certain public spaces” have been identified, and where the sound volume must be turned to zero at 11 pm. In the event that a bar is located next to housing, a sound level is allowed – measured from the home’s bedroom – that does not exceed 30 decibels between 7 pm and 11 pm, and 25 decibels between 11 pm and 7 am.

Another picture of Robadors 23 bar, this time of the exterior.

Photo: Dani Codina

So how loud is 25 decibels? “It’s basically silence. We asked for soundproofing of bars so that homes nearby were not disturbed by noise”, said Granados in the digital newspaper Catalunya Plural a few days after the ICUB circular was issued. “Even so, 95 per cent of complaints about live music venues do not relate to the music itself, but rather to the noise that is generated outside the establishment. Working groups comprising representatives of the districts, residents and the local police are now considering ways of intervening in the event of conflict”.

“It’s not live music that is the cause of neighbourhood conflicts, but rather what’s happening on the street – Granados insisted in this interview –. There’s a huge number of bars showing televised football matches, during which people shout “goal” or go out onto the street to smoke, but that’s OK”.

At night, the decibels in Ciutat Vella seem to be amplified. In the centre of Barcelona, several small venues that have live music are close to each other, as is the case with Sidecar and Robadors 23. Not to mention all the other bars with their round-the-clock opening hours, mainly for tourists, every day of the week; after all, it’s tourists who can party every day, who don’t have to get up early the next day. It matters little if it’s a Tuesday or a Friday.

Ciutat Vella is the second poorest district in the city, after Nou Barris. Its income per capita is €14,481. At the same time, according to 2015 data from the Sociological Research Centre (CIS), Ciutat Vella is, along with Eixample, the district with the most tourist accommodation: 55% of all hotel beds are in these two districts. The city has added almost 20,000 hotel beds since 2005, with 367 hotels and 27 aparthotels. According to the Municipal Services Survey, the number two worry of residents in Ciutat Vella is tourism, surpassed only by job insecurity.

The district is a testing ground in many respects, as in the case of the coexistence between residents and music haunts. The district councillor, Valencia-born Gala Pin, has implemented policies aimed at disciplining merchants. The latest policy affects everything related to tourism and leisure: Barcelona has frozen licences in Ciutat Vella for a year. There will be no more hotels, bars, nightclubs, bike rental establishments or tourist information services in the central district during this period. This one-year moratorium will allow the City Council to review the plan relating to public establishments, the hotel industry and other areas of activity. The aim? “To organise, prioritise and minimise the impact of turistic activity on residents”, says Pin.

According to the councillor, nightlife is one of the district’s main problems, and it negatively affects residents’ sleep. The usual hustle and bustle broke record levels last summer, with occupancy rates similar to the levels experienced before the crisis.

The heads of venues (small, medium or large) know that money talks in English, and if they want to carry on being full each night they need to adapt their programming accordingly or go non-stop. Neverhteless, it’s not entirely the fault of the schedulers: the real pull factor these days is festivals, not traditional music venues. Either way, the effect is that the identity of venues is suffering, as they have started to offer an amalgam of styles: the more the merrier. In general, the identities that marked European nightlife in every city at the end of the last century have run out of steam: Berlin is no longer so techno nor Paris so French house. And Barcelona is no longer so… wild.

The power and appeal of festivals

Lluc Casares, saxophonist for the band Pol Omedes Special 4tet, playing in Jamboree, Plaça Reial.

Photo: Josep Tomàs

An increasingly important part of these tourists, and it is a growing trend, is coming specifically to Barcelona for its summer music festivals. Primavera Sound, where half of the audience are foreigners, Sónar, Cruïlla. The formula is simple: marathon sessions of bands and hundreds of barrels waiting to spurt beer.

Aurelio Santos makes it clear that he is never going to be able to save enough money for a three-day pass for such an event. He has been linked to the live music scene in Barcelona, organising concerts, for more than 20 years. “People, especially younger people, are able to work and save enough money for tickets costing €200 for up to two or three festivals each summer, but for the rest of the year they are unable to watch live music.” He’s clearly irritated, almost angry, raising the tone of his voice.

He is coordinator and compere at the WTF Jam Sessions at Jamboree, a renowned jazz club in Barcelona. His is the voice saying “Thank you for respecting live music”, something he has repeated every Monday for some 15 years. “The musical entertainment model that has been promoted is based on festivals”, he says. “Instead of choosing regular live music in small venues, it has all become concentrated. People get their dose of jazz at the Jazz Festival in Barcelona, indie music at Primavera Sound and electronica at Sónar. They want an escape, to show off, to create an identity for themselves. If you’re not going to Primavera, you’re nobody.”

Aurelio Santos belongs to a group of freaks – that’s how he classes himself – who watch live music four or five times a week. “In Barcelona, I don’t think that culture is taken for what it is: it’s one of the most important catalysts of any civilisation. As far as the new legislation goes, it’s like prescribing paracetamol for the pain of an injury caused by a crash at 200 kilometres an hour.”

Friday of poetry at Heliogàbal, at Ramón y Cajal street.

Photo: Dani Codina

On the roller blind of the Heliogàbal bar, in Carrer Ramón y Cajal, in Barcelona’s Gràcia neighbourhood, you can still make out – painted in a graffiti style – the last poster for the festival they hold in summer coinciding with the neighbourhood celebrations. It’s a long time since locals and non-locals holding beers and rolling one cigarette after another disappeared from the doorway. It’s been days now since the venue was last packed out, exceeding – this is one of its problems – the limited capacity of 39 people. With the cancellation of the British band Crushed Beaks in January, the Heliogàbal announced it was temporarily stopping its activity as a music bar. Coinciding with the coming into force of the regulations for amplified music, the establishment also closed the bar area.

As the protagonist of a demand shared with many other places in Barcelona, the Heliogàbal announced that it was forced to close until September at least. The reason for the closure was the lack of a proper activities licence, which meant that police inspections always ended in a fine. While the new regulations were awaited there was no choice but to close. The Heliogàbal (2012 City of Barcelona award) also cancelled the special programme of events to celebrate its 20th anniversary. ‘The bar doesn’t make enough to cover the cost, so the only solution is to close’, said the Heliogàbal management at the time. The news came after the Gràcia venue organised a concert at the Razzmatazz (‘Pay the fine’: the name said it all), with which it raised almost 16,000 euros thanks to the collaboration from friendly bands and an enviable network of supporters. With that it was able to pay most of the almost 22,000 -euro debt it had built up with the administration.

In spite of the closure, the owners of the bar found a way round the situation; they kept the Ronda season of concerts alive at the Sala beCool, which for them was a lifesaver during the months of hardship and a relief valve for their followers. And they got the light shining again behind the Helio’s roller blind. The premises opened intermittently some weekends until the end of the year, to house the 18th edition of its quarterly season of poetry, and even scheduled the occasional concert.

Recover the integrative side of the night

Living in Portugal’s capital is a Catalan man who has dedicated his doctoral thesis to rethinking how Barcelona’s nightlife is managed. Jordi Nofre, a sociologist and researcher at the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, won the Youth prize in 2009 from the Catalan Youth Agency (ACJ) for his work L’agenda cultural oculta (The hidden cultural agenda). That same year, he gained his doctorate from the Human Geography department of the Universitat de Barcelona.

In his thesis, Nofre argued that Barcelona’s night scene had been “purposely overlooked” by the Government. “Very often, policies for action make reference to the city by day, while the city at night is segregated in terms of space and time.” Nofre spoke of an orchestrated night scene: “Night-time in Barcelona has been used by government authorities as a strategy and a mechanism for the social, cultural, political and moral cleansing of the city. It is a double play by the Government in complicity with the elite who run the nightlife in Barcelona because, essentially, it generates a lot of money through tax systems and tax revenues.”

Jordi Nofre, who is currently participating in a process of regeneration for the port of Lisbon, expands us in videoconference some of these concepts. In a telephone interview we asked him to identify these elites. “Barcelona is just entertainment and fun. There is no industry anymore. The entrepreneurs are the ones who decide the model, not of tourism, but even of city”, states bluntly.

But this model can be combated with political will, in the opinion of the sociologist. “Why does the City Council keep using public money to promote Barcelona as a tourist destination, while forgetting the underground cultural circuits and youth music scenes that would allow the smallest establishments to survive?”.

“If the use at night of public spaces is inseparable from our culture, then tell us so.” Jordi Nofre envisages the use of university credit programmes to educate students on the use of nightlife and public spaces, risk management and respect for residents and urban landscapes…

“The absence of nightlife projects in Barcelona makes it very segregated on a social level”, he continues. “Latin nights are found in one place, the jazz scene in another, the Chinese in another, North African lads board the train to Mataró. The night scene is a space-time continuum which is absolutely there for discovery in terms of social integration. My question is this: if we see that nightlife is profitable at the same time as being an opportunity for social integration, then why doesn’t the City Council open nightclubs that offer different programming?”

The invention of the night mayor

The saxophonist of the Pol Omedes Special 4tet, Lluc Casares, often returns to Barcelona from Amsterdam to play in bars like Robadors 23 or Jamboree. Although he picked his destiny as a means of pivoting towards the United States – the local conservatoire offers an exchange programme – it seems that the Netherlands capital has seduced him enough to become his home.

He explains that “there are more bars that offer live music (small venues, bars) in Amsterdam, while official establishments (auditoriums, concert halls) benefit from a more regular crowd. Cultural consumption is higher”. Unlike Barcelona, the Dutch city has spent years thinking about its nightlife scene: nightlife has been planned and is understood as the space for socialising and for the inclusive civic cultural expression to which Nofre was referring.

One of the pioneering measures brought about by this night-time model in Amsterdam is the concept of the Night mayor, a mediator responsible for managing and improving relations between business owners, residents and the City Council. One of the first proposals by the current night mayor in Amsterdam, Mirik Milan, has been to increase the opening times of venues in the Red Light district, which will now be open 24 hours a day, and to schedule shows, talks and live music during the day. The model has been so successful that it is already being replicated in cities like Paris, Zurich and Toulouse.

Casares is not pessimistic about the future of those who make a living by performing live in small venues. If the music is good, the scene will be saved and people will be able to live off it, he believes. “If we look after music, then music will look after us.”