According to the census, more than three hundred languages are now spoken in the country whose capital city is Babelona. While this linguistic richness constitutes a major social and economic asset, it is also a cultural asset existing within the fragile balance of a particular ecosystem.

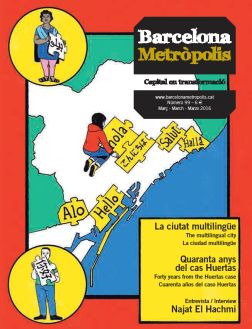

Barcelona has become multilingual. The city that proudly and confidently spoke to the world in Catalan, Spanish, English and French during the 1992 Olympic Games is today an even richer and more diverse linguistic habitat, a reflection of our globalized planet. According to the census, more than three hundred languages are now spoken in the country whose capital city is Babelona. While this linguistic richness constitutes a major social and economic asset, it is also a cultural asset existing within the fragile balance of a particular ecosystem.

A taxi with its ‘occupied’ sign in Catalan. Above the Texas cinema, the only cinema that exclusively offers films translated into Catalan.

A taxi with its ‘occupied’ sign in Catalan. Above the Texas cinema, the only cinema that exclusively offers films translated into Catalan.

Photos: Pere Virgili.

Eight international organisations are working in support of a project called the Protocol to Guarantee Linguistic Rights, whose aims are to offer guidelines for the defence of language equality and to support endangered languages. If Barcelona is to be a benchmark for multilingualism, it must start by protecting its own language, Catalan, in a way that ensures that it can be assertively used without becoming a kind of imposition or source of conflict. At this point in time, when some would like to see our society fractured by linguistic differences, it is more important than ever to encourage harmony and respect amongst speakers of different languages. Addressing someone who looks foreign in Catalan should be interpreted as a sign of respect. Were this not the case, we would be demonstrating bigotry towards people whose linguistic identity is not discernable by the colour of their skin, physical features, surname or mode of dress, while at the same time denying large sectors of the population access to the Catalan language.

There should be no room for linguistic laziness. Languages should be thought of not as problems but as opportunities, not as barriers but as bridges that facilitate the incorporation of new people and communities into the life of the city. To the extent that we can all understand one other, we should also put the languages of new arrivals to good use to further the development of Barcelona, a city which needs to forge economic and financial links with the vast network of cities that are re-drawing today’s world maps.

As Francesc Xavier Vila points out in his article on the languages of Barcelona, the city’s multilingualism is nothing new. It goes way back to the time when the area known as Barkeno (inhabited by Iberians, Greeks and Carthaginians) became Barcino (which Latinised natives and colonisers alike) and later Barchinona, where vulgar Latin lived alongside Classical Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Amazigh and Barbarian languages.

An Amazigh speaker is the subject of the interview which kicks off this edition of Barcelona Metròpolis: Najat El Hachmi, a writer of Amazigh origin and winner of the Ciutat de Barcelona prize. Today, she is one of the rising stars of Catalan literature. Najat El Hachmi is a representative of the new wave of immigration of the 1980s which brought non-Europeans to our country. While no longer an old empire’s metropolis, today’s Barcelona sets the scene for stories written by both local and foreign authors such as German Stephanie Kremser and Frenchman Mathias Énard, a recent winner of the Prix Goncourt. The rise of Najat El Hachmi and the other writers mentioned is an indication that the life of this country and this city that we are building is destined to be ever more diverse and heterogeneous. Barcelona’s narrative is no longer in the hands of any one social class, media group or powerful lobbying group with a branding concept. Nor is it in the hands of a City Council that works to empower and give a voice to the citizenry: together these citizens will build the Barcelona they want.

Barcelona will achieve linguistic sovereignty if it is able to give Catalan its rightful place in the world. It will also serve as a haven for languages if it is capable of welcoming – without being condescending or pretentious – speakers from all around the world, including those of the most endangered languages.