The architect Itziar González, head of the team that won the ideas competition for the Rambla, features in this issue’s interview.

Photo: Pere Virgili

The job of politicians and urban planners is to detect urban pathologies and solve them. The remodelling of La Rambla is an opportunity for an exercise in administrative therapy (on a small scale) that encourages citizens to believe that they have plenty to say and something to do to improve their surroundings in a non-defensive way.

“You made yourself with hasty hands, / in deep, nebulous centuries”, says Joan Perucho in his Ode to Barcelona. Yes, cities are built with the haste brought about by need, but also with the order required for coexistence. The city of Barcelona was built on a hilly landscape, with slopes and plains, tunnels and bridges, now climbing a mountain, now descending to the sea. A city of palaces and hovels.

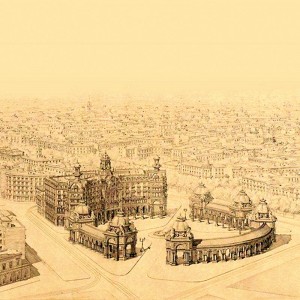

Whether it’s the work of illuminated visionaries, insaciable speculators or homeless newcomers, a city is the sum of sedimented successes and impatient error. The city is also everything it’s given up on being. In La Barcelona desestimada (The Rejected Barcelona), Carme Granadas collects urban and architectural projects that wound up locked in a drawer for financial and political reasons, or because of changes in fashion. Can you imagine if Rubió i Tudurí’s idea of moving the Barcelona Zoo to the Park Guell had been carried out? Or if the Plaça Catalunya was a ring of kiosks designed by Antoni Gaudí? The history of Barcelona is also the history of its regrets.

Two projects for remodelling Plaça de Catalunya: the one by Pere Falqués from 1891 and the graduation project by Pau Bajet, a student at the Escola d’Arquitectura, dated 2013.

Photo: Institut Municipal d’Hisenda

The job of politicians and urban planners is to detect urban pathologies and solve them. In other words, to detect the ailments in the chakras of the city, the places where energy and movement concentrate and allow the city to flow. The case of the Plaça de les Glòries, turned into a four-highway knot in the ‘60s, is a quintessential case of an urban pathology, which consisted of placing the Barcelona of cars above the Barcelona of people. The urban planning of Diagonal Mar made it clear that we were sacrificing a central point of the movement of citizens in favour of the mobility of vehicles. A chakra turned into an ailment.

This distinction between movement and mobility is one of the pillars of the project for remodelling La Rambla promoted by the Km-Zero collective led by Itziar González, the winner of a public competition. A former councilwoman of Ciutat Vella, an architect and urban therapist, González explains in the interview at the start of this magazine that we need to save La Rambla both from the monoculture of tourism and from disenchanting momentum. Km-Zero’s project aims to become a laboratory in participation that could mark the start of a new relationship between citizens and the administration. González is clear that managing the city isn’t the same as building a city, which is always the manifestation of collective expression. To bring about this community revitalization, innovation in the way the city is governed is essential. We need innovation involving a new set of rules, innovation that generally comes together with a new type of language.

For those of you who have heard the word “empowerment” time and again without really understanding what it means, here’s a concrete example. The remodelling of La Rambla is an opportunity for an exercise in administrative therapy (on a small scale) that encourages citizens to believe that they have plenty to say and something to do to improve their surroundings in a non-defensive way. The Km-Zero collective proposes a horizontal method, which takes into account both the opinions of those involved (neighbours, organizations, businesspeople, etc.) and the observations of technicians. It’s impossible to redo La Rambla without the cooperation of all sectors. However, we also can’t do it without a series of inalienable values: the transparency, delicateness and the closeness of the Administration, and especially urbanity in the most primordial sense of the world. Here, this means the protection of the trees, the promotion of movement over mobility, the recovery of a maritime character and the nodes (or chakras) that make up the promenade and the integration of Barcelonians into their rich cultural fabric. We also shouldn’t forget the tourists that brought with them the light of other shores and who, one August afternoon, were run over.