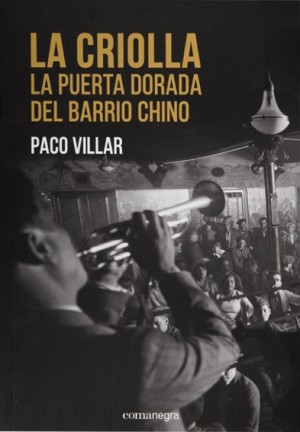

La Criolla. La puerta dorada del Barrio Chino

Author: Paco Villar

Publisher: Comanegra and Ajuntament de Barcelona

256 pages

Barcelona, 2017

Transvestitism and brazen homosexuality reigned supreme on Carrer del Cid. So, too, did treachery, dishonesty and the broken, questionable condition of the people. The owner of La Criolla, who presided over a bar that would turn from a seedy joint into a hotspot, started by playing dirty and ended up worse off.

The book called Historia y leyenda del Barrio Chino (The History and Legends of China Town) (La Campana, 1966) was — and still is — a surprising endeavour, a map of the most dismal (and cheerfully) celebrated bars in that area outside the old city walls, often referred to as El Raval, both loved and loathed by locals and foreigners alike. In that book, Paco Villar (Barcelona, 1961) catalogued in text and photographs the euphoria and the follia – or folly – as well as the misery, for several decades from the start of the 20th century. It is a singular book to which this return to the topic has now been added, with a more unrelenting narrative thread that follows the origins and the apogee of a tavern set up in the heart of a street of ill repute that, during the First World War in 1914, would refine its artifices: “Or, more precisely, a bar with a pianola, pale electric lighting and large mirrors covering the sheets on the wall.”

It is impossible to reflect in this review the power of the images on display here. Some of them are so incredible, such as the one of the famous man they called Flor de Otoño (Autumn Flower): “The most enigmatic character of all those who performed at La Criolla… an anarchist activist, homosexual and cocaine addict who, by night, used to don makeup and regularly visit the dance halls along Carrer del Cid.” Or the photo of Carmela, a pretty girl who would go on to be elected Miss Barrio Chino in 1934; only up-close could one tell — because someone sitting at a nearby table warned the innocent bourgeois type who had succumbed to her charms — that she was, in fact, a man.

Transvestitism and brazen homosexuality reigned supreme on Carrer del Cid. So, too, did treachery, dishonesty and the broken, questionable condition of the people. The owner of La Criolla, who presided over a bar that would turn from a seedy joint into a hotspot, started by playing dirty and ended up worse off.

Participants in the Miss Barri Xino transvestite contest in 1934. Image published in the book La Criolla. La puerta dorada del Barrio Chino.

China Town embodies many stories, starting with the chronicle of its poverty; so miserable, so tough and unhealthy it was to be a part of it, so naturally lugubrious. The private rooms without sheets on the beds; the children that went running by, the sight of women renting themselves out, by the hour, in full view.

Paco Villar is a career journalist. What would have become of us without him? What would have become of him without Francisco Madrid and his account of the night he dared to sleep in one of those hostels with 140 hard beds and millions of fleas? Or without Sebastià Gasch, devoted admirer of a fourteen-year-old girl who danced like a wild animal? “Carmencita [Carmen Amaya] remains impassive and statue-like, haughty and superior, with an indescribable racial nobility, inscrutable, distracted… Then, suddenly, a jump. And the gypsy girl dances. It is indescribable. Soul. Pure soul. The transcription of soul through dance.” Or without Juli Vallmitjana and his insurmountable descriptions of that world that he intimately explored?

The history of prostitution and drugs is reflected here in its evolution as a small-time business — the nearby port, the sailors who arrived with consignments of cocaine (the mandanga) — and its process of globalisation. Likewise, the girls who brought the Polish Jews are the same ones — through the connection with Buenos Aires — that an Argentinian Jewish writer (César Tiempo) wrote about, in his stories about girls, who threw themselves from a balcony, drawn there by false promises of work and marriage (and they are the same enslaved women we see today and about whom we know not their terrible reality).

The reader will not forget this account of glitter and grime: the poverty of a Barcelona that all of a sudden had to become beautiful — during the 1929 International Exposition — the ingenuousness of a mechanical pianola and the décor of angels and blue skies. The poor, obese Mrs Rosa who died in her brothel, having received the last rites from a priest who reluctantly entered the premises. For this reason, through all this glitter and grime, the reader will not forget the celebrities who began to appear, such as the Nobel prize-winning writer, Jacinto Benavente; the stage actress, Margarita Xirgu; and even the French novelist, Jean Genet, who was in it up to his neck.

A dark tale, a story of two shades. Like how Flor de Otoño trafficked explosives by day and painted his lips by night.