The city that wanted to be the Paris of the South has run out of places to hide from the traffic and the noise, to go for walks without having to window-shop and to read leisurely, and offsets the coldness of being a capital with its impressive figures. Maybe a new realism is called for to bury the self-satisfaction of beautiful Barcelona. The City Council will have to recover the city for less showy and more sustainable uses.

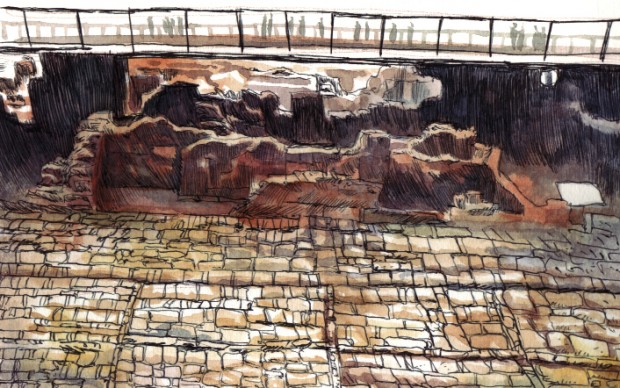

Within the grid of the Born’s subsoil, the visitor steps on the paving of streets demolished by King Philip V of Spain. This, together with the archaeological remains on exhibit in the centre’s museum, gives us an idea of life in Barcelona three centuries ago. Words, scattered like the strewn remains of dead animals, show us, in their strangeness, the extent of the passage of time and the changes in Catalan material life. Words banished from the vocabulary into oblivion after the reality they described fell apart. Also cast out by the Nova Planta Decree, these words harbour, in the mystery of their etymology, the secret of a life destroyed. They, and others like them, are the ruins of the language.

The visit allows you to imagine the hive of activity that was eighteenth-century Barcelona, otherwise evident in the neighbourhood’s street names. In the nineteenth century, the Catalan’s homo faber nature was further accentuated by the proliferation of factories and workshops, which leaped across La Rambla to take over the large monastic areas evicted by the riots of July 1835. At the end of the century, the factory-owning middle classes felt strong enough to spearhead the first ever Expo in Spain. Many of the stories of modern Barcelona begin in this booming time, when the city, in the words of Verdaguer, harboured pretensions of becoming the Paris of the South. The result of a collective psychology accurately described by Narcís Oller, any attempt at being equated with Paris meant becoming the economic and cultural capital of the Mediterranean. Today, a good century after that gust of optimism, we can now do the maths surrounding the construction of one of the most compelling urban myths of the last century.

The beginning of the twentieth century heralded the slow conversion of the industrial city into a tourist city. Like Milan and Turin, Barcelona had been a city devoted, body and soul, to trade and industry. In 1908 it also began to see itself as a magnet for affluent tourism that gravitated towards the Côte d’Azur and which, a few years later, would discover Biarritz. That same year, the Society for Attracting Foreigners launched the two slogans that have done most to advertise the city: cosmopolitanism and “Mediterraneanism”. The magazine Barcelona Atracción, the first of its kind in Spain, mixed in cultural elements through photos of the Sagrada Família, historic buildings and the new modernist architecture. Basically the same formula with which the post-Olympic city councils have sought to dignify a purely commercial operation. Today, tourists drawn by the genius loci continue to gobble up Gaudí, Picasso, Modernism and all things Gothic. The novelty is provided by a few kilometres of beaches, thousands of bars, restaurants, nightclubs and shops where quality is becoming gradually more conspicuous by its absence. Cultural assets developed later, such as the Fundació Miró, Fundació Antoni Tàpies and the MACBA, play second fiddle in terms of popular pulling power. But despite the cultural pretext, post-Olympic Barcelona continued to bank on the aforementioned hooks as soon as the promotion of tourism became a conscious goal. In 1929, in the book Barcelona, published during the International Exhibition, Manuel Vallvé boasted of the city’s “magnificent geographic and climatological conditions”.

These conditions, patented with the name of the place’s brand, are now Barcelona’s leading economic asset. It is a unique case of specialisation among the world’s enterprising cities. But calling Barcelona enterprising might now be described as an anachronism. The financial, technological, cultural and political importance of a big city is inversely proportional to its tourist specialisation. In view of the over-sizedness of the spaces associated with leisure activities, it cannot be denied that the conversion undertaken in 1908 has been successful. The balance proclaimed in the title of the 1913 album Barcelona artística e industrial eventually tilted in favour of the cultural pretext for foreigners seeking entertainment. Barcelona has paid for this success dearly, as is wont to occur when quantity is placed before all other values. Divested of production facilities, which had been farmed out to the outlying areas, Barcelona reinvented itself as an epicurean space with a sheen of modernity administered by design-driven and cheque-book cosmopolitanism. If Porcioles once realised that populism demanded that a pro-Franco mayor dance La Sardana, the socialist Clos felt compelled to dance La Samba atop an open vehicle so that Barcelona would resemble, just for one day, a Latin American metropolis. Porcioles, governing an industrial city that had expanded at a rate that hindered planning, needed to be forgiven for being pro-Franco. Clos, like previous mayors, was convinced that he was governing a global capital and believed that he should be forgiven for being Catalan.

Overwhelming banality

The sale of the last square meter of space dashed the opportunity to give Barcelona back some real quality. Everything done after the Spanish Civil War, despite the prestigious prosthetic add-ons, is staggeringly banal. More than a city of architects, over the last three-quarters of a century Barcelona has been a brilliant every-man-for-himself scenario for builders. Architects have contributed with the ideology of a compact city, defending densification, paving the few remaining open spaces, reducing the landscaped and tree-covered areas that are a sign of civilisation in big cities around the world to a minimum symbolic expression. In a completely built-up city, the possibility of demolishing the lower part of the Raval district, to turn it into the second lung of a city gasping for air, was lost. “What a waste,” said the nineteenth-century middle classes, alarmed at the width of the streets of the Eixample neighbourhood. And in order not to waste, the twentieth century opted for “multipurpose spaces”, “facilities”, promoting the Raval and the dignification of neighbourhoods through the strategic location of “urban art”. No opportunity was missed.

The city that wanted to be the Paris of the South has run out of places to hide from the traffic and the noise, to go for walks without having to window-shop, to read leisurely. But it offsets the coldness of being a capital with the ephemeral greatness of impressive figures. For example, those of a clientele in search of sensuality, one that leaves a few banknotes on the dressing table before taking their leave. “The stage for Europe’s largest gay festival,” as one newspaper headline put it. And which was justified a few lines further down: “100 million euros for the city.” Or by aspiring to be the world mobile capital merely by hosting an annual trade fair, while spending on research and development has plummeted to below 2% of the GDP. This psychological compensation of a rather unpleasant reality is embodied in the straitjacketed triumphalism with which, last June, it was announced that El Prat airport would receive the A380 Airbus daily, “the world’s largest aircraft,” while Barcelona airport has become a low-cost hub.

A climate of opinion that confuses laxity with tolerance has prevailed all too often, the upshot being that citizens have been left utterly defenceless. The current city council promised to put this state of affairs right and promote civic-mindedness, and things have undoubtedly improved. But anyone moving about the city will still see numerous cases of vandalism, abuse of the transport system, mockery of the law or downright bad manners. Barcelona has a tradition of these things. Noucentisme, which tried to fight them, was idealism, and as such it failed. Nowadays, the city is neither immune nor impervious to the new perils of globalisation (organised crime, human trafficking and Islamic terrorism), threats that outgun the municipal government, entering the domain of immigration policy, the penal code and collaboration between the regional police and State Services.

Perhaps a new realism is called for to bury the complacency of the beautiful Barcelona promoted by the councils of the great auction. The city planning department is currently focusing on sustainability and on attracting productive investments. Its managers fully realise that tourism should be less predatory and more select, and therefore more minority. But if it wants to progress from intention to execution, municipal policies will have to keep the hotel lobby at bay and recover the city for less showy and more sustainable uses. Either that or turn Barcelona into a dead city like Venice, but with the dirtiness, spatial codes and alternative authority of Naples. Because Barcelona, which lost its Austrian influence in 1714, seems perilously trapped inside the “Mediterranean brand”.