We are witnessing the triumph of a city without a clear nickname or unambiguous image, but which has become an international tourist destination. So let’s look for another brand. However, do we really believe that by saying that Barcelona is Gaudí or Barça or the Mediterranean or a feast of talent we will add to the value that its mere name already evokes?

At a time when the words “branding” and “brand” are on everyone’s lips (as if they were thoroughly modern) and are applied to so many things, including countries and cities, it might be worthwhile recalling that “brand” actually comes from Old English and first surfaced in Beowulf circa the year 1000 (as brond), literally meaning something burnt, marked by fire. What I mean is that the whole thing goes a long way back, and that the kind of brand referred to – although it has been known extensively over time to Barcelona thanks to people like Al-Mansur, Berwick, Espartero and Pricolo – is neither easy nor sweet to relate to a city.

When we talk about the “Barcelona Brand” (or that of Spain, or Formentera) we are talking about associating the city with an image. About imagining it in the sense of the first meaning in the dictionary: forming a mental image of it, representing it in our mind. We might say “adjectivising” the city, or re-baptising it, or even tuning it, but we are ostensibly dealing with conceptual images (figures: symbols, allegories, metaphors) and are therefore talking about imagination.

Throughout its long history, Barcelona has not only been given different names (Barcino, Barchinona, Barshiluna) and heard them pronounced in different ways, it has also seen how whatever was tacked on to its core name changed according to the circumstances: the parallel adjectives, nicknames or names associated with the city’s name. Of all the nicknames that in one way or another are still with us, perhaps the oldest is “Cap i Casal”, from the Middle Ages, from the times when the city was the headquarters of the county of Barcelona, and was added to reassert its importance (the same name was used in the Kingdom of Valencia for the city of Valencia). The most common nickname also comes from this period (or perhaps from the reference to the period): namely the “Ciutat comtal” [city of the counts], which through mental sovereignty has the drawback of turning the capital into, so to speak, a mini-capital. Subsequently, in the early 17th century, Miguel de Cervantes set a long episode of the second part of Don Quixote in Barcelona, where the city is evoked as a “repository of gentility” (“that repository of gentility, refuge of wayfarers, asylum of the poor, homeland of the brave, avenger of the wronged and home of harmonious and lasting friendship, a city unique in its setting and beauty”): the formula went down well, and is in fact still used to this day, with a clear preponderance in the times when Spanish was the official language of those who wished to refer to the city of Boscà, Agustina d’Aragó and Juan Antonio Samaranch.

Come the 19th century and industrialisation, Barcelona was sometimes referred to as the “factory of Spain”, although many of the leading lights in that economic and cultural recovery preferred the ring of the “Paris of the South” (a stroll through the Eixample district shows that this was not merely an abstract idea). Nevertheless, for a Parisian of the ilk of Prosper Merimée (librettist of Carmen), it was little more than “a city that masquerades as a capital and is the spitting image of a provincial industrial city”. In any event, industrialisation did lead workers to get organised, sparking heightening social tension which, at the turn of the century (and well into the 20th century), turned the city’s streets into the reason why Barcelona, when Sant Jordi’s day was not yet a holiday, was also called “the rose of fire”. Or, if you want a brighter and more literary version (penned by Joan Maragall in his Oda nova a Barcelona [New ode to Barcelona], in the same year as the Tragic Week), “the Great Enchantress”, an image chosen by the art critic Robert Hughes as the title of one of his books about the city.

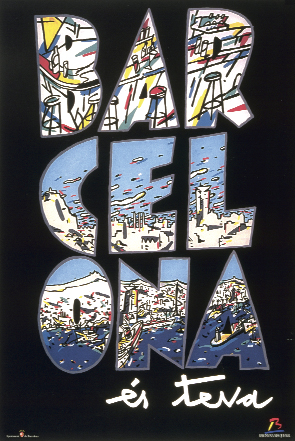

After the Civil War, for decades Barcelona was Franco’s “City of fairs and congresses”. Perhaps even into the merry 1980s, when a poster by Mariscal and a song by Gato Pérez joined forces to conjure up, in the broken-up “Bar Cel Ona” [Catalan for “Bar Sky Wave”], a cheery seaside summer-holiday destination years before the Olympic Games were to open up the city’s waterfront for us to rediscover that the city actually had beaches… reachable, to boot, by underground or bus. These were the years when Eduardo Mendoza retrospectively novelised the era of modernism, talking about “the city of marvels” (the title of his novel from 1986), when the City Council launched the “Barcelona, posa’t guapa” [“Barcelona, get pretty”] rehabilitation campaign, a popular, successful and long-lived initiative (three characteristics that rarely come together in politics, not even at local level). Just before the 1992 Olympic Games bequeathed us Cobi and the idea of a compelling and attractive city, parallel to the “power” which, perhaps divested of real arguments (“Ella tiene poder, ella tiene poder / Barcelona es poderosa, Barcelona tiene poder” [“It has power, it has power / Barcelona is powerful, Barcelona has power”]) was attributed to it by Peret and Los Manolos (“romántica reina, la que nos parió” [“romantic queen who gave birth to us all”]) when Olympic excitement peaked. After that, at the turn of the century, the self-same municipal government exalted Barcelona (with ads, which is how these things are usually done) as “the best shop in the world”, underlining the importance, attractiveness and diversity of the city’s trade, seen as an asset already related to the burgeoning boom of international tourism.

Having or being a brand

We have thus seen how Barcelona’s many nicknames have referred to its being a capital (albeit a minor one), to gentility, hard work, enchantment, explosive appeal, sun and beaches, shops and a relatively unfounded and self-satisfied power (but nevertheless quite convincing, at least on the inside). When all is said and done, if taken together they might not be such a bad description of the city, although obviously the question about the identity of the target still remains, not to mention the telling detail that all these nicknames have never worked as a sum, but rather as tags like the ones people used to stick on luggage, always over the previous one, replacing it.

What Barcelona might be imagined from each one of the nicknames the city has had and from each and every one of the different proposals that have recently appeared on the scene? One of the latest, the title of the film that Woody Allen came to shoot among us (Vicky Cristina Barcelona), was an original but ultimately laughable attempt at a new moniker crafted from wooliness and many of the clichés of crossover success in globalised times. What metaphor and nickname might we give Barcelona now, post-Cobi, to put the image of a pretty, powerful and sensational shop behind us? The essayist Jordi Amat, in an article titled precisely “Matar el Cobi” [“Kill Cobi”], holds that the Tripartite, somehow Cobi and “Maragallism” [referring to the former mayor, Pasqual Maragall] began to become part of a past without true heirs. What we have now is certainly the triumph of a city (more than a model) without a clear nickname or unambiguous image, but which has become an international tourist destination, which (with Salou, Can Pastilla and Benidorm lurking nearby) runs the risk of Barcelona being associated with a different kind of brand (the three S’s of “Sun, Sand and Sex”, or the four of “Sun, Sand, Sex and Sangria”), one that theoretically everyone wants to avoid, not to mention Roberto Saviano, who says that he feels safe in Barcelona because the Mafia never kills in places where it does business. So let’s look for another brand. However, do we really believe that by saying that Barcelona is Gaudí or Barça or the Mediterranean or a feast of talent we will add to the value that its mere name already evokes?

The names given to Paris, the “Ville Lumière” (actually coined in London almost two centuries ago), New York, the “Big Apple” (through a campaign sponsored by the city in the past seventy years), or Rome, the “Eternal City”, neither help nor hinder them. They are not random examples: Harold Bloom holds that Barcelona is a “city-of-cities”, like the three above, and that it is like them because they are cities of the imagination.

The question is whether Barcelona is in the same league as Paris, New York and Rome – and can therefore hold its own with or without a brand – or whether it desperately needs a revamped brand as a motor or lever and subsequently run the risk of getting stuck with this would-be happy (and inevitably one-dimensional) brand forever, like a piece of chewing gum or a stain (just as Avignon was the “City of the Popes” or Dubrovnik “the Pearl of the Adriatic”). In thirty years, Barcelona has gone from living to be shown to living off being shown (with many citizens subsequently feeling as if they were mere extras in many parts of the city, rather than the main characters). This process has needed no brand (only the excellent work of the Barcelona Tourism consortium). Scrambling to come up with a new one now says a lot more about a weakness we dare not confess rather than any well-conceived medium-term strategy. Sometimes, debating adjectives denotes a lack of willingness to talk about (or imagine) the noun.