Nada [Nothing] by Carmen Laforet, and The Time of the Doves by Mercè Rodoreda are two parallel works that complement each other in many ways, becoming two parts of the mosaic of the same historical reality. Read back to back, the sensation is that although they were written in different languages (the former was originally written in Spanish and the latter in Catalan), they are nonetheless part of the same whole. Nada is the voyage of enlightenment of Andrea, who comes to Barcelona having just turned 18, whereas the story of Natàlia/Colometa is that of a young woman from the neighbourhood of Gràcia, charting between when she is going out with her first husband-to-be through to the early years of Franco’s dictatorship. The time settings of both novels overlap: Andrea’s account focuses on her first year in the city, not long after the Civil War, whereas The Time of the Doves straddles the pre- and some of the post-war years. In terms of social class, they can both be read as two complementary volumes: Rodoreda basically focuses on the working class, Laforet on the decadence of a well-to-do family that has fallen on hard times. The poverty and hunger of these years run through both novels, although these topics are presented very differently: Andrea is hungry because she is unable to administer her orphan’s allowance, whereas Rodoreda talks about hunger as a direct consequence of the war.

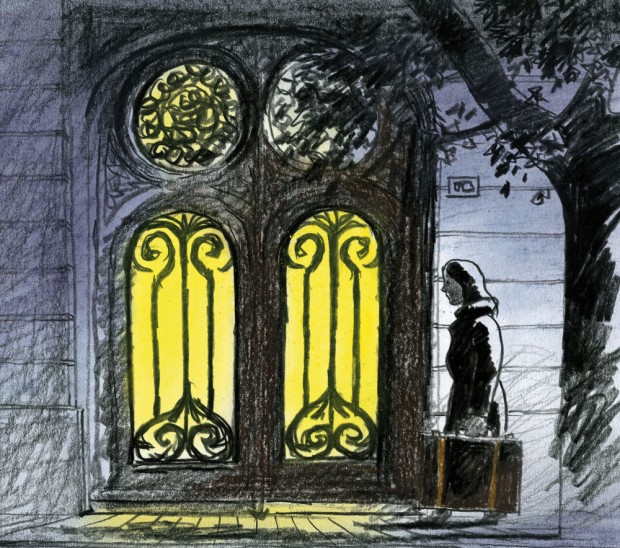

For Nada’s main character, the city is of great importance, so much so that it becomes like another character, perhaps the most prominent one after Andrea herself. She arrives at night, by train, from a town that is not disclosed to us, driven by the expectations of the freedom which the cityscape represents in her imagination. Her parents’ house in Carrer d’Aribau is the main setting for all events. The flat represents the space of oppression, where a whole age and social class is shut in, falling into decadence. Laforet’s heroine’s disappointment leads her to take to wandering the streets of the city frenetically, particularly attracted by the old part, the Gòtic neighbourhood, and the Red-Light District. This action of traipsing the streets of Barcelona constitutes a veritable release for the girl.

The life of Rodoreda’s Colometa, on the other hand, plays out in the district of Gràcia, which she hardly ever leaves. At some point, when the woman is also wandering the streets, she makes it as far as the Jardinets de Gràcia and Avinguda Diagonal. The descriptions of the neighbourhood evolve with the changes in Natalia’s life: at the beginning it is bright, happy and full of life, epitomised by the dance in the square from which the novel’s original Catalan title takes its name, the Plaça del Diamant, and she works as an assistant in a sweet shop, but as the heroine’s life becomes murkier so too do the descriptions of streets and places. Of course, the most claustrophobic moment is the Civil War. We are told about the time leading up to the war, the air raids and the deprivations, and the historical situation, initially a backdrop, gradually comes to the fore. And Nada begins just where The Time of the Doves ends, affording us a rather vivid snapshot of the Barcelona of the age.