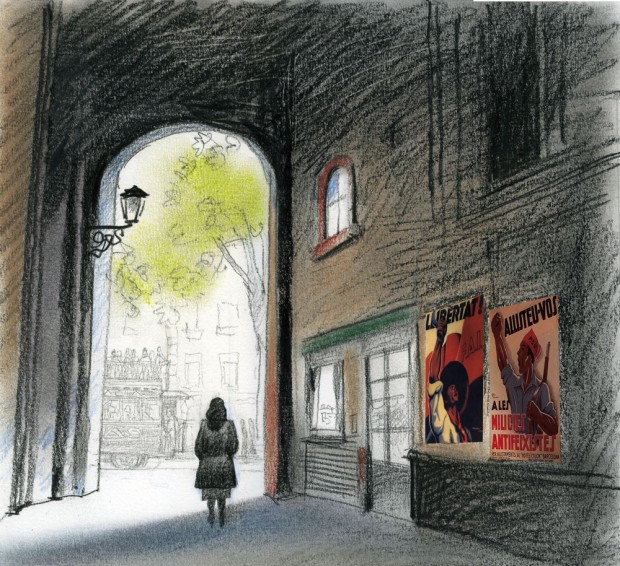

Considered one of his best post-war novels, Incerta glòria [Uncertain Glory] was first published in 1956, but his author extended and modified it until the final version of 1971 was reached. Barcelona is depicted as a rearguard city, where walls are covered with Republican propaganda and searchlights sweep the air in search of bombers. In the last parts of this work, published under the title of El vent de la nit (‘The Wind of the Night’), the main figure is the dark Barcelona of the defeated.

The Barcelona of Incerta glòria [Uncertain Glory] is a rearguard city, where the walls are covered with posters of Republican propaganda and the anti-air searchlights pierce the night sky on the lookout for Italian bombers. It is also an inward-looking, almost metaphysical city, mirroring the tormented religiousness of the narrator, Cruells, and the spiritual transformation of the main character, Trini, a young anarchist who has been converted to Christianity. Therein lies its lack of definition: so much wandering around Barcelona and so few precise references.

Trini, born in Carrer de l’Hospital (where her parents still live), goes to clandestine masses in a flat in Carrer de l’Arc del Teatre, and traipses along La Rambla and around La Boqueria until she stops in what appear to be the limits of her reduced geographical area: Plaça de Catalunya, Ronda de Sant Antoni, Carrer de Pelai, whose empty shop windows eloquently depict the shortages in the city. The funny thing is that over the three years of the conflict Trini does not live in the old Barcelona, but rather in Pedralbes, in the luxury home of Lluís, her partner and father of her son. In the novel’s six hundred-plus pages the reader will find no episode set in the extensive urban area that separates Pedralbes and Ciutat Vella. There is a huge gap between the Barcelona where Trini spends the nights and the Barcelona she moves about in during the day: the Eixample somehow does not exist in Incerta glòria.

And the funny thing is that I had always thought that Joan Sales was a gentleman of the Eixample. Where could I have got that strange idea from? I suppose from one of the key episodes in El vent de la nit [Night Wind], the sequel to Incerta glòria, where Sales recreates one of the most outstanding events in the Catalan church’s resistance to Franco’s regime, the priests’ demonstration of 11 May 1966. That day, more than 200 priests marched from the Cathedral to the police headquarters on Via Laietana to hand in a document protesting at the abuse perpetrated on students and workers. One of these priests was Cruells, seeking a kind of personal redemption through this act of civic valour. When the priests stood firm in front of the police station, the police simply laid into them and then chased them to the place where they went in search of refuge: the Jesuits of Carrer de Casp. At last, the literary geography of Sales spilled beyond the limits of Ciutat Vella into the Eixample!

The city of El vent de la nit is the Barcelona of the riff-raff and unscrupulous victors, but above all the dark Barcelona of the vanquished. Joan Sales would have ended up being the classic gentleman of the Eixample had his life not been violently pummelled by the defeat. In fact, until that defeat drove him to exile, he lived in number 36 of Carrer del Rosselló, a rationalist building from 1930 which still stands today (albeit transformed and run-down), and which was the first residential block built by the architect Josep Lluís Sert. Between his return from exile in 1948 and his death in 1983 he lived well away from the centre, in the Coll district, virtually in the countryside, a rugged and remote territory the writer’s family used to refer to as “Wuthering Heights”. It was from this vantage point that Sales gazed upon the transformation of his old Barcelona.

Pingback: Torna Barcelona Metròpolis | Núvol