There are fictional cities that seem livelier than real ones. Few authors have erected a Barcelona so much anchored in popular memory, so present in the collective imagination.

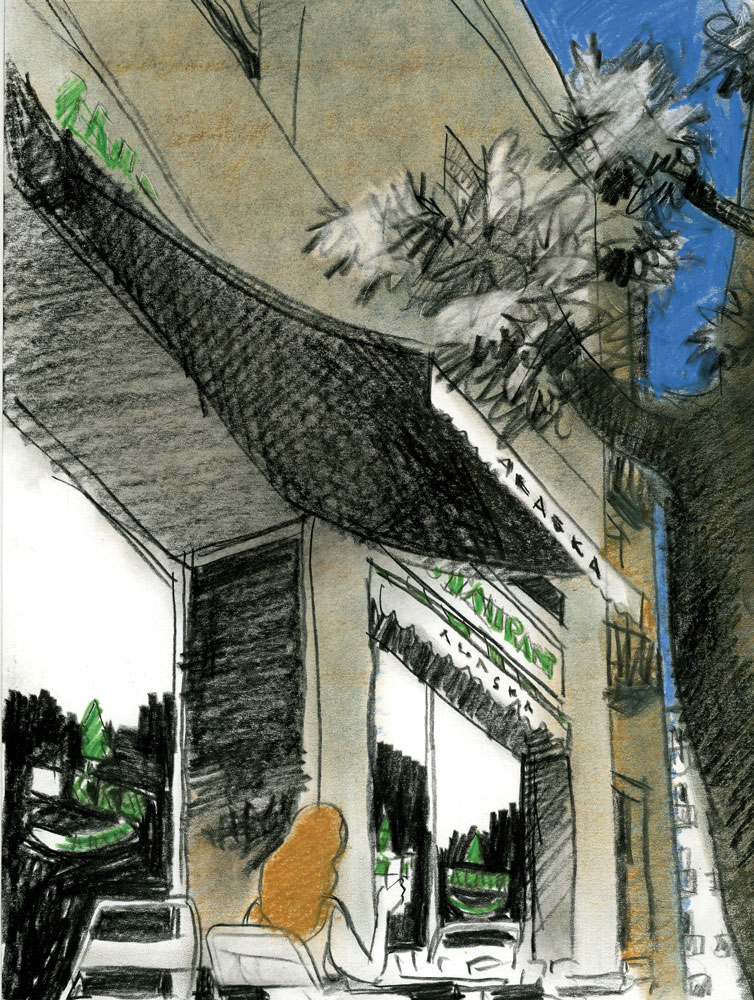

For eight years I lived a stone’s throw away from the Alaska bar, on the corner of Passeig de Sant Joan and Carrer del Pare Claret. The Alaska was one of Carmen Broto’s haunts. The story goes that Broto, a prostitute and plaything of Barcelona’s high society, lived on the other side of Pare Claret and very often, on returning home in the wee small hours, would have a nightcap in the bar. In January 1949, three men murdered her and abandoned her body on waste ground in Carrer de la Legalitat, in one of the most talked-about and most covered-up crimes of the early post-Civil War period.

Like many people, I became acquainted with Carmen Broto’s blonde hair and killer perfume when Juan Marsé portrayed her in The Fallen (1973), a novel that visits his childhood and war scenarios, mingling personal memories and aventis [tales]. Marsé turned the spotlight on the Alaska bar, a meeting point for subversion and low life, and around Carmen Broto he wove a web that played out in the neighbourhood streets, in the cinemas, in the dark backrooms of shops and on the trams that gave off sparks. That first read was my passport to Marsé’s world, a simultaneously true, realistic and mythical map of Barcelona.

Novelists create bonds of affection with the settings they choose for their books. It is never a random choice. The city that they invent and the streets and houses they recreate lie at the core of their characters – they mark them – and go on to become an important part of the reader’s memory. There are paper cities whose realism is more vivid than the real ones. In the case of Juan Marsé, this identification is particularly intense. Few authors have created a Barcelona so anchored in the popular memory, so present in the collective imagery. In fact, the urban essence of Marsé’s novels lies in his interest in characters who live on the fringe, who can change classes like one who moves to a new neighbourhood, or for whom the unfamiliarity of unknown places is like an escape valve. La oscura historia de la prima Montse [The Dark Story of Cousin Montse], Ronda de Guinardó, Un día volveré [One Day I’ll Come Back], Lizard Tails… Each new title extends the map, while also detailing familiar streets. From the hovels of El Carmel to the dark Red-Light District, from Plaça Rovira to the Ritz hotel, the Tibet Restaurant to the protective shadows of Parc Güell, the Roxy cinema to the Delicias bar…

I could continue to plot the place names of the Marsé map, but clinical list-making leads nowhere. I am more interested in the figuration of a literary city that is shared by other narrators – and which eventually forms a personalised topography in each reader’s memory. I will give you an example. I am thinking about Últimas tardes con Teresa [Last Afternoons with Teresa] (1966), which is perhaps the novel where Barcelona’s presence is most decisive. Talking about Pijoaparte’s character, Marsé writes: “He has just left the house, which is part of a beehive of hovels located under the last turn, on a platform hanging on the city: from the road, on approaching it, the sensation of walking towards the abyss.” At that moment my reader’s memory flies to El carrer de les Camèlies [Camelia Street], by Mercè Rodoreda – also published in 1966 – on the day Cecília Ce shacks up with Eusebi in the shanty town: “The hut only had two brick walls; the other ones were made of tin, with pieces of wood and sackcloth stuffed in the chinks.”

The same operation would serve for other cases: Marsé is echoed in Blai Bonet, who is echoed in Vázquez Montalbán, who is echoed in Sagarra, who is echoed in Josep M. Planes, who is echoed in Vila-Matas, who is echoed in Josep Pla, who is echoed in Enrique de Hériz, who is echoed in Marsé… They are different takes, even opposing ones, but the mystery is that they are all mirrored in each other, because the city is a huge kaleidoscope.

Pingback: Torna Barcelona Metròpolis | Núvol

Pingback: LlegeixB@rcelona » Arxiu del bloc » Barcelona cinema… SI TE DICEN QUE CAÍ (Vicente Aranda, 1989)