The verb to be is at the heart of poetry, of identity, of the pleasure of hearing Catalan being spoken. Who are we in a language that was, has been, has become and vibrates, after so many centuries, in the present ambiguity of our iPhones and our melancholic, civic voices?

It is a story. I did not see the night. I immersed myself in the night one summer solstice in Barcelona. When I came out of the Montbau metro station, I walked to the entrance of the Parc del Laberint. It is a story. I did not see the night. I left the labyrinth at the break of dawn, when the women had become couples, ardent shoulders and arms among the cypress trees. The taxi dropped me off at La Rambla, near Carrer de Ferran.

On 24 June 1990, four hundred women gathered at the Parc del Laberint d’Horta to celebrate the last night of the IV International Feminist Book Fair. Most of us took the metro at Drassanes station. At each station we left behind a goddess, who has watched over solitary female passengers ever since.

La nuit verte du Parc Labyrinthe, Éditions Trois, Laval, 1992.

Twenty-five years ago I made my first trip to Barcelona, a journey which inspired a short text written with fervour, because the city had awoken in me an immense desire to discover and invent narratives that would etch it into my mind forevermore. The city was full of the colours and twinkles produced by the tiles, mosaics and stained glass at the whim of the light. The sight of the palm trees made me feel happy there and prompted me to multiply the comparisons which inspire a zest for life. Barcelona touched the sea and history, and the people spoke a language with layers of memory and silence that intrigued me. In addition, I had met audacious, creative poets and women in that city, like Cinta Montagut and Anna Bofill. The living force of Barcelona has never disappointed on any of my subsequent visits. I have engaged in a dialogue with this energy on each of the six stays which followed that of 1990, all of a literary nature, motivated by my participation in the Poetry Festival, for a meeting of women poets (1996), for a colloquium on Quebec literature, for the publication of my book Baroque at Dawn (1998) and of my collections Installations (2005) and Museum of Bone and Water (2013), translated into Catalan by Antoni Clapés, and also for the discussions on translation within the Anada i Tornada [Return Journey] programme (2015). Not until very recently did I say to myself that the time had come to attempt to understand what it was about this city that resembled me and to comprehend the emotions and thoughts it evokes in me.

Barcelona is a city that excites and calms me at the same time. I walk differently in Barcelona than in other cities, often with my head tilted upwards so my gaze meets the façades, the tiles, the stones, the bricks and mosaics, so I can cross paths with the parabolic art that Gaudí loved so much.

The aesthetic of ornament works well in this city, where one is able to walk, eat well, reason, shuffle through books and listen to and speak poetry. To walk and to think. To eat and to reason within a framework of friendship. I mean, to go to the essence of well-being and of the pleasure of thinking and creating. To know that the sea is there, within arm’s reach, to love each play of shadow and light that falls on my eyes and skin.

When I think about Barcelona, the Catalan city, and I address her, I always do so knowing that she will answer me in French.

Barcelona is a city of the verb to be.

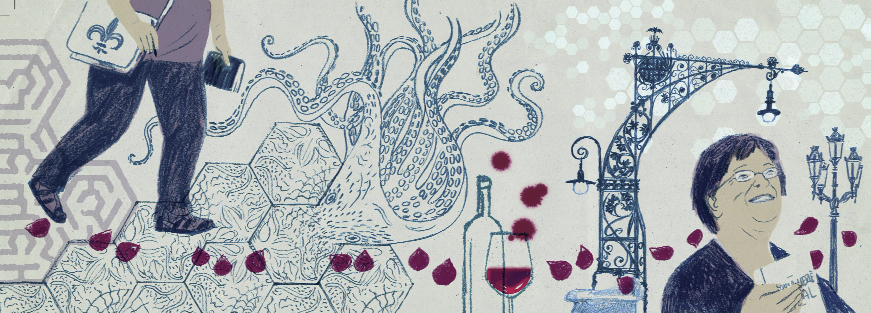

This same verb, to be, is at the heart of poetry, of identity, of the pleasure of hearing Catalan being spoken. Who are we in a language that was, has been, has become and vibrates, after so many centuries, in the present ambiguity of our iPhones and our melancholic, civic voices? Moreover, for a Québécoise like myself, Barcelona is associated with a solidarity, the linguistic and political effects of which hit close to home. I am convinced there is a jewel which passes through the subterranean land of relationships between Québécois and Catalans. A jewel which naturally lights up when you walk through the intimate alleys of Ciutat Vella or down the spacious Passeig de Gràcia, which arouses a strange delight in me, no doubt due to the association with the words beauty, architecture, salamander and trencadís [broken mosaic] or the names of poets like Jordi de Sant Jordi and Maria-Mercè Marçal, or the bookmarks I made from the rose petals I bought in the midst of a fevered crowd one 23 April.

My Barcelona is poetic, cultural and utterly friendly. When I say “cultural”, I mean original, fanciful, far from conventional and, despite everything, full of wisdom. Now I think of Cloud and Chair, by Tàpies, an outline, a striking take-off. There, presented with traces of our ability to become airborne and to be carried away, I always find myself in a state of learning and of inspiration. Now I think of the museums, very often surrounded by a park, as though art knew how to breathe, and of libraries, including the library at the Ramon Llull Institute, devoted to books translated both from Catalan and into Catalan that serve to give an idea of the influence of and interest in Catalan literature throughout the world. I dream that we in Quebec might be capable of materialising a similar concept of presence and transmission through translation, which in my view protects humanity from its own erosion. I mention translation because it is a mainstay of my writing, but also of my relationship with Barcelona. Now I think, among others, of Antoni Clapés, who some years ago created a vital movement for the exchange and circulation of poems and poets so we could see and feel from within the thoughts and images that each of our languages allows us to imagine. I also think of the dynamics of the exchanges with Lydia Anoll, Carles Biosca and Dolors Udina, with whom I have recently had the pleasure of sharing moments of reading, of debate and of creation, which have made us journey to the frontier of what is possible and impossible in our respective languages. I also think of the marvellous show Com elles (Like Those Women), presented by Mireia Vidal-Conte, Odile Arqué and Marc Romera, in which I was delighted to find some of my poems; of the Jaimes bookshop, where Québécois French meets Catalan at the evening readings; and of the publisher Cafè Central and its director, Víctor Sunyol.

It’s a little strange, but in this article I’d also like to use the word streetlight. Whether or not one thinks of Gaudí or of Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince, the word streetlight forms part of Barcelona, because it recalls, day and night, the signs of beauty scattered around the city at dawn and twilight, this city of extreme urbanity and of the sea, which awakens sensations at the most unexpected times: the suggestion of a wrought iron spiral, the sudden sight of a façade made of balconies shaped like masks, the ceramic blue that peeks through the young foliage of April. The streetlight is an architectural and aerial punctuation that projects my inner dreamer through time, in the same way that the hydraulic mosaics do, which might just as well display octopuses as snails and starfish, and which vibrate under our feet to launch us through space. Barcelona invites one to feel the four elements powerfully, and I am convinced that this plays a subliminal role in the attraction people feel for the city.

When I think about Barcelona my mouth waters, no doubt for the octopus, cured ham, olives, salmorejo and red wine, and at the same time I always find myself in an invisible living: that of thoughts, sensations and emotions that only I know, crossing paths with beings as if that were the way to a long journey on which the paths in turn cross with history, landscapes, faces, ancient or contemporary living forces, Santa Maria del Mar or the Walden building, at the other end of the city.

Barcelona is a city of the verb to be, a city which glows from one language to another, from one tenderness to another; it is a reflection, in the visual sense of the word and in the sense of thought. If a part of its body lies in the stone and the tiles, the other lies in the light and poetry. It is simultaneously a labyrinth and a horizon, a place where my voice fires up with ease. “That’s what literature is about, getting closer.”

Gran article de Nicole Brossard. Només hi ha una observació. L’editorial Cafè Central té doble direcció: Antoni Clapés i Víctor Sunyol.

Nascut a Barcelona l’any 1927, i enamorat d’aquesta ciutat tan maltractada, m’enorgulleix i m’omple d’admiració el llegir l’article de la Nicole Brossard.

I sí, trobo que descriu perfectament ‘la ciutat del verb ésser’.