Clotilde Cerdà in Havana, wearing the cap of the city fire brigade.

Photo: Album of Clotilde Cerdà i Bosch. Biblioteca de Catalunya

During the final third of the 19th century, feminist and anti-slavery thoughts and actions could have consequences. The composer and harpist Clotilde Cerdà i Bosch, daughter of the painter Clotilde Bosch and her husband Ildefons Cerdà, experienced it first–hand.

Clotilde Cerdà i Bosch was born in Barcelona either in 1861, according to the civil register, or in 1862, according to a diary entry by her father, Ildefons Cerdà. It is said, however, that the architect of Barcelona’s Eixample district was not in fact her biological father; although he acknowledged that she was his daughter and gave her his surname, he excluded her from his 1864 will and testament, written the same year in which his marriage to Clotilde Bosch broke down.

Clotilde Cerdà playing harp, aged six.

Photo: Album of Clotilde Cerdà i Bosch. Biblioteca de Catalunya

At 15 years of age and already a celebrity, internationally renowned for her harp concerts — and known by the stage name Esmeralda Cervantes —, Clotilde Cerdà arrived in Cuba via New York and Philadelphia, where she had performed at the international exhibition in 1876. Cuba’s first war of independence had broken out; it was not the best context for musical events, so the Captain General of the island, Joaquín Jovellar Soler, recommended that she postpone after hearing of her intentions to visit. But Clotilde paid him no heed, performing at Havana’s most important theatre, the Teatro Tacón. She wanted to go to Cienfuegos but was stopped because the trip was deemed too risky. Performances aside, she also befriended members of the independence movement who were for a republic and against slavery. Enrique Trujillo, a member of the Spanish-American Literary Society, founded in New York by the Cuban writer José Martí, introduced the harpist to the movement. “In her, the cause of Cuban independence found a powerful ally”, he wrote. The Spanish Government was lying in wait, but for the time being it left the harp player alone.

Providing a “bright education” for women

The wait continued when in 1883, on her return to Barcelona — where two years previously she had gained the loyalty of a masonic lodge —, she began the process of creating an educational centre specifically for women, with the aim of offering them a “bright education, focused more on the practical than on the theoretical”. Its purpose was to provide women with access to training and to demand their right to professional work. Thus, two years later, the Academy of Sciences, Arts and Offices for Women (ACAOM) was born at No. 10 La Rambla. Clotilde Cerdà surrounded herself with women who already had successful careers and recognised standing, such as the poet Josepa Massanés, the doctor Dolors Aleu i Riera — the first female medical doctor in Spain — and the journalist and novelist Antònia Opisso, a key member of the academy’s organigram.

Clotilde Cerdà with students at her academy, 1885.

Photo: Album of Clotilde Cerdà i Bosch. Biblioteca de Catalunya

The project — created, funded and managed by women — was very well received. The number of students was growing day by day. Attendance to the evening classes reached 270 and no more applications could be accepted owing to the small size of the centre. A year after its inauguration they set out to construct a brand-new building that would meet the spatial and organisational needs of the academy.

At the same time, the academy’s secretary, Antònia Opisso, published Diario de un deportado (Diary of a deportee), a novel in a diary format. The novel’s protagonist and supposed author was Carlos Atregui, a Cuban resident who was deported to Spain after being accused of holding anti-slavery and independence-related beliefs. Through this work, Antònia Opisso took part in the debate regarding slavery, which was still being practiced despite an international agreement prohibiting it. The writer openly declared herself to be opposed to slavery through the words of her protagonist: “I’m an abolitionist”.

Royalist threat

In search of money to expand the academy, Clotilde planned a trip to the United States to seek the funding she had been unable to find in Barcelona or elsewhere on the Spanish peninsula. Since 1st January 1887 she had known that certain royalist sectors were not only refusing to support the continuation of the project but were expressly opposing it. Conde Morphy, a count and secretary to the Queen Regent of Spain, María Cristina, said in a letter: “I thought that you aspired to play the harp very well or even to be a great artist, […] but then one day you appear in Cuba, as if wanting to solve the problem of slavery through your influence and presiding over demonstrations and meetings that have nothing to do with art. And now I see you setting yourself up as defender of the Catalan working classes and the education of women.” He went on to recommend/order that she keep quiet; if she did not, she would have to face the consequences. It was a bona fide threat: “If the newspapers print nonsense, do not pay them any heed, nor involve yourself in making accusations, nor take on responsibilities or give any advice without sufficient knowledge of the issue at hand because if you do, the result will be counterproductive.”

Conde Morphy’s threat materialised. The Academy of Sciences, Arts and Offices for Women had to close down owing to a lack of support and its budgetary deficit. On 29th March 1887 Clotilde Cerdà made the academy’s accounts public: “The difference between the deficit (12,960) and the amount remaining to be paid (3,750) has been settled by the Director.” Clotilde went into exile, accompanied by her inseparable mother.

European exile

The harpist and activist wandered half of Europe, without a fixed abode anywhere. On 1st October 1888 Jacint Verdaguer, a Catalan writer and poet, wrote: “I watched with great sorrow the setbacks that eventually took her away from her homeland; but remember, we are all exiles in this world.”

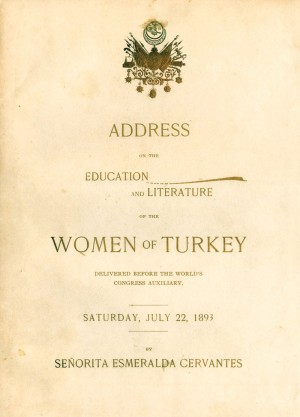

Cover of a pamphlet with the lecture she gave at the Chicago World Fair in 1893, on women in Turkey, under her artistic pseudonym.

Photo: Album of Clotilde Cerdà i Bosch. Biblioteca de Catalunya

From Constantinople, where she was invited to play a concert and where they wouldn’t let her leave, Clotilde — sitting on “soft ottomans, on the terrace covered in vines” — wrote to Víctor Balaguer, a politician and author, on 22nd September 1892: “My friend, I founded the Academy of Sciences, Arts and Offices for Women and, as if I had founded a school of bad habits, so everything bad was unleashed upon me. With a loss of 22,000 pesetas I closed it and took flight to countries where I would be appreciated and paid my worth.”

The academy lasted for barely two years, but it was not the only failing. The women’s conference that was to be held in Palma never took place either. La Ilustración de la Mujer (The Enlightenment of Women) magazine, for which Clotilde wrote at least one article, would also be short-lived. All these projects, which created spaces for discussion and training, with a view to improving living conditions for women and men, and for participating in social development from a female — or why not say feminist? — perspective, were shut down.

The threats and her exile did not stop her. When she was in Turkey, Clotilde Cerdà was invited to the World’s Columbian Exposition, to be held in Chicago in 1893, to give a talk on the education of women in the East. She went and spoke about the Education and Literature of the Women of Turkey. As part of the exposition she also played in a concert conducted by Theodore Thomas and in a private performance for the President of the United States, Stephen Grover Cleveland, and his wife, Frances Folsom.

Her journey continued to Brazil, where she became the delegate for the international peace association Alliance Universelle des Femmes Pour la Paix (Universal Women’s Alliance for Peace) and where her mother died and was buried in the city of Belém do Pará. From there, Clotilde moved to Mexico, giving music lessons in the capital’s conservatoire; she had already stopped performing in concerts. Later, she returned to Barcelona and, in 1915, she settled permanently in Tenerife, where she died in 1926.

Clotilde Cerdà was not an exception. As Christine de Pisan said in the 15th century, we would find more women like her if we took the trouble to look for them.