The years of the Spanish Republic were a golden age for Aurora Bertrana, not only from a literary point of view but also for her public activism.

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the birth of writer Aurora Bertrana (Girona, 29 October 1892 – Berga, 3 September 1974), a good reason to look back at the woman and her work, both of which have been largely neglected. Those of us who studied books by her father, Prudenci Bertrana, at school never heard her name mentioned.

She was a much-celebrated author during the years of the Spanish Republic, largely because of her travel books. But when she returned from exile in Switzerland years later, a new more troubled phase of her life began. Her rebelliousness and her free spirit did not sit well with the Spain of that time, which was visibly going backwards. She had been educated and found success in Barcelona, and now she was returning as a member of the losing side. Because Barcelona was where she developed her literary career, we can now look back at her work in the context of this ever-shifting city, shaken by the vicissitudes of history.

A girl from Girona in Noucentista Barcelona

Although literature was always her great passion, Aurora Bertrana had musical leanings from a very early age. But Girona soon felt too small to her: “My parents had decided to send me to Barcelona twice a week to take cello lessons and to practice with an orchestra”, we read in her Memòries fins al 1935 (Memoires up to 1935). And as a teenager, she arrived at the Acadèmia Ainaud on Gran Via.

Straddled between the World Fair of 1888 and the International Exposition of 1929, the artistic movement known as Noucentisme was trying to Europeanise Catalonia through common sense, while Modernisme was attempting to individualise it through whimsy. The writer and feminist Carme Karr — friend of the family, Editor of the magazine Feminal and the woman behind several feminist projects — advised her to move to Barcelona and stay at her home for a while, where she was welcomed as a daughter and met notable figures from the arts world, including women like writer Dolors Monserdà and painter Lluïsa Vidal. The young Bertrana was admitted to the Municipal Music School, then run by the composer and conductor Antoni Nicolau and located in the Castell dels Tres Dragons in Parc de la Ciutadella. She was a girl from the provinces who drank in everything she could in a city that was in a process of transformation and a hive of cultural activity.

Later on, her father’s work brought the whole family to Barcelona. They found a flat in the Barri Gòtic, with views of the convent of Santa Clara, where they all lived together. The family was never financially comfortable, and when poverty tightened its grip Aurora’s life took a tumble in the blink of an eye: “We held a brief family meeting and the motion was passed unanimously. That was how I went from being a future concert cellist, a future (great) composer or professor, to being a simple cellist in a women’s trio.”

Aurora Bertrana played in the mornings, in a not-so-elegant café on the Rambla de Santa Mònica, and lived alone in a flat in Plaça del Rei. The setting for this new phase in her life was the bohemian Barcelona of the “roaring twenties”. It was then that she started to take an interest in the condition of women and joined the teaching staff of the Women’s Cultural Institute and Public Library, set up by educator Francesca Bonnemaison. She then departed to Geneva to study the Dalcroze Method. She returned as the wife of a Swiss man, Monsieur Choffat, the name by which she always called him.

Long live the Republic!

Aurora Bertrana in Tahiti, where she lived between 1926 and 1929, and where she began her literary career by publishing several very successful travelogues.

Aurora Bertrana and her husband lived in French Polynesia from 1926 to 1929. From that remote corner of the world, she sent travel chronicles to the press, and captivated her readers. Her literary vocation had finally started to blossom. The resulting book, Paradisos oceànics (Oceanic Paradises) was published in 1930 to great success. Following this period, the couple returned to Barcelona and went to live in a solitary old house in Montcada and, later, in a grand apartment on Diagonal.

It was during those years that Aurora Bertrana was at her most radiant, on both a personal and a literary level. She was part of the writers and journalists scene, along with Irene Polo, Rosa Maria Arquimbau, Anna Murià and even Mercè Rodoreda. She was commissioned to write articles, asked to give lectures and was made Chairwoman of Barcelona’s Lyceum Club, an association of women with an interest in culture and the arts, set up in the image of its more famous namesake in Madrid. Her inner feminist came out to society and she proved her political engagement by standing as a candidate for Esquerra Republicana in the 1933 elections, but was not elected. Barcelona was at that time a launch pad for the feminist cause. Women had never achieved such heights of freedom of movement.

In 1934 she published a book of short stories on exotic themes, Peikea, princesa caníbal (Peikea, the Cannibal Princess). The title character has a love affair with a white man and in the relationship it is she, not he, who calls the shots. It is an expression of Bertrana’s role as a spokesperson for women who set their own path. 1935 saw the publication of L’illa perduda (The Lost Island), a young adult novel written in partnership with Prudenci Bertrana. In 1936 her fourth successful book came out, El Marroc sensual i fanàtic (Sensual, Fanatical Morocco), the result of another voyage. In the words of Neus Real, who has studied her work in depth: “Thanks to the press and her books, Aurora Bertrana became one of the most prestigious female voices in leftist circles”.

The aerial bombings of 1938 caught her at home in her flat on Diagonal. The windows shattered and the iron railings of a balcony were ripped out and thrown against the wall of the study, which she had left just a moment before. The only thing for it was to leave the country. In June 1938 Aurora Bertrana, alone, left “a Barcelona in ruins, starving, bombarded and filthy”. Behind her she leaves applause and prestige. Bitter experiences and a decade of nostalgia lay in store for her in Switzerland.

The sad, dark days of post-Civil War Barcelona

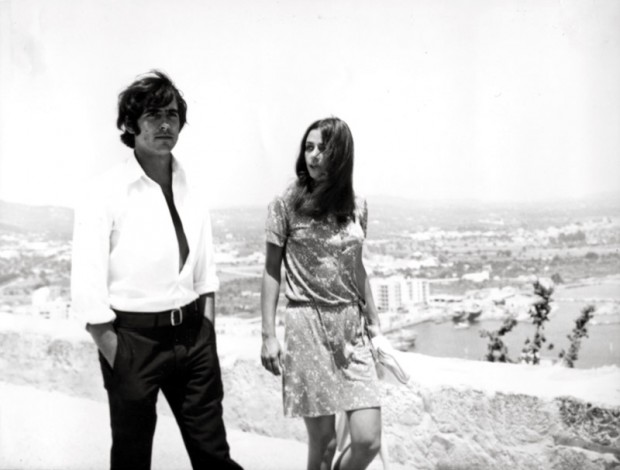

Joan Manuel Serrat and Emma Cohen, stars of the film La llarga agonia dels peixos fora de l’aigua, directed by Francesc Rovira-Beleta and based on the novel Vent de grop.

It is highly symbolic that in her memoires Bertrana leaves no trace of her experiences on returning to Catalonia, to the hypocritical Spain of General Franco. Her written testimony pauses in early 1949, when she returns to the sixth floor flat at number 4, Carrer de Llúria where she would live with her mother and aunt, her father now dead. “These last years, I have not lived. It is hard to explain. These are years without any adventure, muffled years, grey years. I have only lived in my writing”, she tells us. This writing, because of the impossibility of having a normal literary career, took on a variety of somewhat erratic registers: Entre dos silencis (Between Two Moments of Silence) and Tres presoners (Three Prisoners) recorded the wounds inflicted by the Second World War; Ariatea has exotic themes, while Fracàs (Failure) reflects societal themes; more sentimental in nature was Vent de grop (Stormcloud), which also found commercial success and was made into a film. Her memoires, 1,000 pages long, gave the perfect closure to her writing.

In 1974, when Bertrana passed away, nobody remembered the teenager who wandered through the Parc de la Ciutadella each morning, carrying her cello, nor the young woman who walked up La Rambla late at night, nor the lady whose literary successes during the time of the Republic became a milestone in women’s social and cultural history. And that is worth remembering.

Felicitats per l’article. Ens has fet més propera a l’Aurora.

Hi ha una data que caldria modificar. On diu juny 1936 ha de dir juny de 1938 ( on es fa esment de la marxa cap a l’exili).

De nou l’enhorabona!

Pau

Gràcies per ajudar-me a conèixer aquesta gran dona, el film no li va fer justícia.