An author with a variety of registers and a novelist of the viscera of classical Barcelona, Montserrat Roig wrote about and experienced deeply everything she had at hand. Her research into Catalans in Nazi camps signalled a turning point in her career. This November marks the 25th anniversary of her death.

Montserrat Roig (1946-1991) left an ever-changing, deepening body of work that to a large extent is still to be discovered: we have not read it closely enough. I’m not talking about a formal assessment of the work, but about the writing the author was proposing and, above all, the modes and manners of the words she used and in which she was deeply immersed. A short life means that we must not lose sight of the writer’s time; it concentrates this time. What Roig did in order to leave a mark and the overall image of the world and of us that she built, in particular while she was dying, since she published daily right up until the end: that is probably what counts the most.

There is a good dose of adventure in Roig: in her words, her expression. She was a woman who wrote and experienced deeply everything she had at hand, irrespective of whether she sought it out or stumbled upon it. The way that life and literature combine is complex; there can be no other way. In Roig’s case, the breadth of tools and spectra of words were her keystone, in parallel to a life experience that was likewise prismatic and hard-working. Theatre, narrative, journalism, television, research on history and memory, travel books, conferences, classes at foreign universities, cultural and media contributions, article writing. Friendships, love relationships, travels, children, editors, political and social changes, editorial changes, and changes in the role of the writer itself from the 1980s. Roig had experienced the rise of the moral figure of the contemporary writer (of varied morals, since the single worldview is from the 21st century, which she did not experience) and was spared from seeing the confusion and decline of that moral figure in the intertwining tendrils of the market.

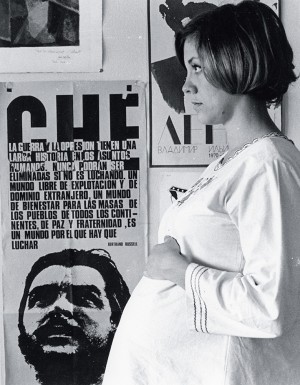

Ever-changing and deepening. Her final works of prose both confirm and display this evolution, day by day. In newspapers, first in El Periódico and later, when she was already ill, on the back pages of Avui. She had fought to become a professional writer, to earn a living by writing, and so she had explored different genres. The recent biography by Betsabé Garcia, Amb uns altres ulls (With other eyes) (Roca Editorial), is a good, dynamic recounting of the tireless work she did, and all without much in the way of publishing networks. In the 1970s she was a media figure, although back then it wasn’t called that. An urbanite daughter of pop culture after all, she had created her public persona from the very beginning and turned herself into a star. The photos by Pilar Aymerich, her partner in crime for many years, bear testament to this: what presence, what glamour and elegance Roig had. And when cancer attacked her, the hour of relentless truth that is illness brought out the self-portrait that the public persona had been hiding: a lucid, serene, combative writer and an excellent reader, who was cognisant of the fact that Franco’s dictatorship had pulled literary training up at its roots and who was, therefore, all too aware of her limits to that point and the power that, despite her illness, journalistic prose could give her.

She took advantage of the eventuality of the irony of life. With her antennae more attuned to inner life – owing to a sharpening, as the writer Maria Marçal, who was also sick, would say a short time later – of the body and the tools when it comes to describing the social and political world, including culture, as both foment and fertiliser of personal and collective life, where words act as precise tools of a geometry of noble expression. As in the case of Marçal, who also died at the age of 45, and of Helena Valentí, who died age 50, I ask myself how much more we would have gained from them had they been able to survive the tyranny of cancer, which had (also) given them so much enlightenment. Roig’s final works of prose are magnificent and are some of her greatest literary legacies.

Inside and outside Catalonia

What would she think, what would she write about this or about that? And one aspect no less important: Roig had taken to heart the aim of strengthening relationships (and translations) between Iberian literatures. She developed contacts outside Catalonia and acted as a cultural bridge. She did the same for the region of Valencia too. I don’t know to what extent she felt appreciated or if anything came out of it; it is, however, reasonable to assume that no one seems to play this role any more.

Something similar happens outside the Iberian peninsula. In terms of contacts and professional visibility, Roig had impact. Some American universities were familiar with her work and valued it. In 2004, in Guadalajara, Mexico, at an international congress, I was asked about what had become of her work, because neither gender literature nor Hispanist scholars were giving due consideration to it any more. I didn’t know what to say. Presentism rules in a way that could be fatal. If you are not here, which means if you’re not alive and you cannot travel here and there to endorse your books, then you are simply not taken into account. Misogyny does the rest.

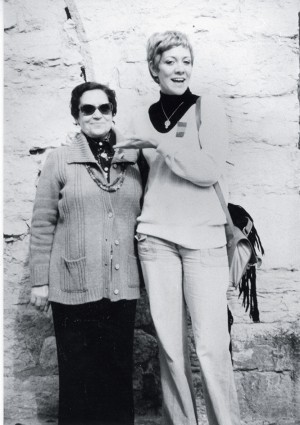

With Neus Català, survivor of the Ravensbrück Nazi concentration camp, at the inauguration of a monument to Spanish Republican refugees in Septfonds (Languedoc) in October 1978.

Photo: Family archive

Roig was, at heart, a woman of her time, in every sense. She cultivated her own vision; often, in her case, as a female chronicler, but not only as that. In this sense, there is, in her books, a strong political, pedagogical desire aimed at changing the ideas received in the consciousness and exploring the vital margins in the area of women’s freedom, with clear discernment that this is a central point of contemporaneity. Like all writers, she was shaped by her early and modern forefathers. While she was from a family that had not entirely broken with Catalan tradition – quite the opposite, in fact – even so, such were the effects of the Franco regime that she was not spared from having to recover a great deal of Catalan literature and pour her heart and soul into interviews that remain essential even today, nor was she saved from the pressing need to consider literature from other contexts, both from literary history and from the present. For her, the feminism of the 1970s represented the gateway to knowledge, which is, in essence, what feminism is.

Linking everything together is this vision of history and of memory. In particular, I am thinking about the extraordinary research on Catalans in Nazi camps, which marked a turning point in her work and in her life. In my opinion, this is one of the central points in analysing Roig’s work, a book that was finally published in 1977, after a long period of financial difficulty.

Roig’s Barcelona

Remembering her should mean reading her, now. We have the above-mentioned excellent biography as a foundation; what is missing is a comprehensive reading of her work, one that considers her fiction in detail and also views it in the context of the overall panorama of her work and, therefore, of the literature of her contemporaries. Time puts everything in its place and it is worth re-reading books perhaps read all too often with condescension and critical negligence. Her novels feature a Barcelona that, in addition to the named characters, exists as another character and sometimes, even, as the lead character. She narrates the history of the city and the neighbourhood she knows best: Eixample, which is where she was born, but it is more than a chronicle – even though that would be value enough. Instead, you can get to know Barcelona from deep down inside it, almost to its viscera.

For such an impenetrable city, that is no small thing. The same could not be said of the many novels in which, after all, Barcelona is just scenery and nothing more, an editorial hook without meaning or sense, a private reference, at the most, for those who write them.