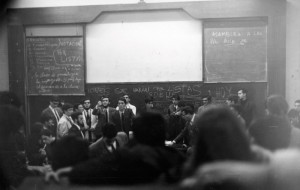

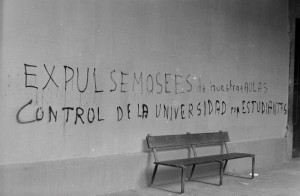

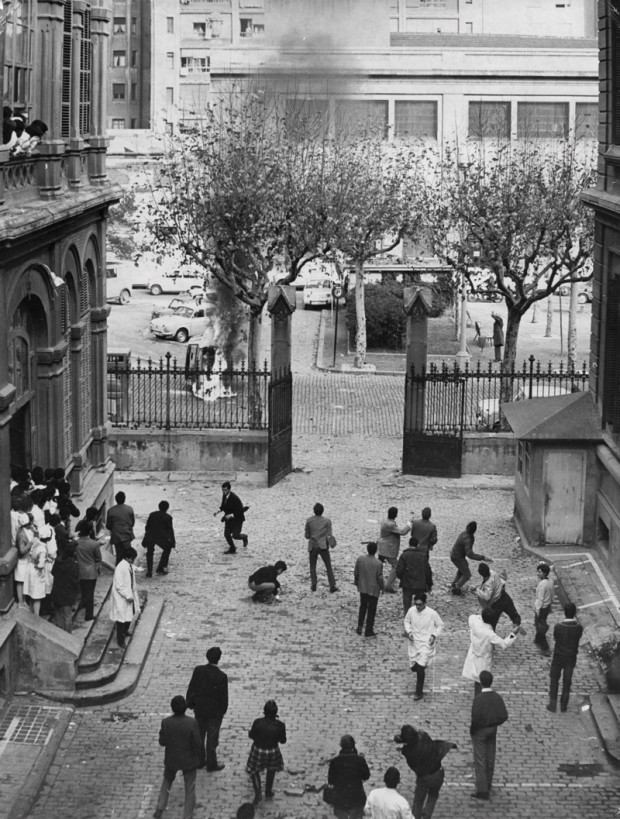

The images illustrating this feature show assemblies, rallies and other events staged by the students of the Barcelona Medical Faculty, in May 1968. The photographer, Josep Pagà Carbonell, took them for the magazine of the Democratic Students’ Union.

Photo: Josep Pagà Carbonell / AFB

It is half a century now since May 1968 in France. In Catalonia, the unrest unleashed a frantic race to show who was the most left-wing, and could take over from the PCE-PSUC as the revolutionary party of the working class. The discourse of the counterculture, meanwhile, added a cultural and subjective dimension to the political struggle: the argument was that the revolution had to begin within each individual.

The events of May 1968 in Paris were immediately heard of in Barcelona, although they had no practical impact until months later, when the new university year began. The task of detailing the events fell to the journalist Tristán La Rosa, who for a long month from 5 May onwards wrote a daily account in La Vanguardia of the student uprising and the social and political crisis it prompted. His reports, which after 11 May revealed an increasingly empathetic style towards the student mobilisation, claimed a place on the front page of the paper until 1 June, when he reported on the demonstration in Paris by supporters of De Gaulle, the latter’s meeting with General Massu, and his far from subliminal message of military intervention, underlined by the manoeuvres of the Second Armoured Brigade on the outskirts of Paris, in case the spirit of Thiers needed to be resurrected. On 2 June Tristán La Rosa, who by then had been consigned to the inside international news pages, drew his series to an end, opening his report with the pronouncement: “The revolution is over”.

Many of us had never read La Vanguardia with such interest, nor would do so again. Tristán La Rosa told us about the barricades, the clashes between students and police, the occupation of the universities, of the Odéon, the general strike convened by the CGT; and filled us, the student left of the time, with belief, arguing that power lay in the factories and “to a certain extent” in the universities… For a month we dreamed of the idea that at the political heart of Western Europe, which Paris still was, a revolution would break out. The dream faded, but its cultural consequences lived on as a daydream, and the awakening came not so much in the form of ideological radicalisation (since the radicalisation of the left had begun in Catalonia’s universities 12 months earlier), as in terms of a renewal of the forms of mobilisation and struggle against Franco’s dictatorship, which had culminated in the founding of the illegal, but not clandestine, SDEUB, the Democratic Students’ Union of the University of Barcelona, forms that gradually wound down over the 1968-69 academic year.

The radicalisation dated from the 1966-67 academic year. Following the successful founding of the SDEUB in the free elections at the start of the university year, and its formal organisation at the Capuchinada gathering, in March 1966 the governmental plans for the APE, the Professional Students’ Associations, were defeated in their second version, when their leader Ortega Escós, appointed by Franco’s government, was bested in a historic verbal duel that took place at the university auditorium with the delegates of the SDEUB, led by Francisco Fernández Buey. The democratic union model spread that autumn to the Universities of Madrid, Zaragoza, Valencia and Seville, while the Comisiones Obreras trade union candidates achieved significant success in the elections for company representatives at the major factories in the Barcelona Metropolitan area.

Some circles, and in particular the student committee of the PSUC, the driving force behind the three student elections of 1966 and the Capuchinada, had their own dream of a union of workers and students, and the possibility of overthrowing the dictatorship, more in the short than the medium term, through an intense mobilisation that would culminate in a political general strike, devised in terms of a mass insurrection.

The student organisation of the PSUC was in personal contact with Catalan university students settled in Paris, some of them refugees and others completing their studies (Irene Castells, Jordi Borja), who passed on news of the climate of mobilisation that already existed in France in 1967, a mobilisation focused in particular on the rejection of the Vietnam War, and inspired by China’s Cultural Revolution. The individuals mentioned were not the only ones with French connections: sections of the Popular University group, the university organisation of the FSF party (the Federal Socialist Force, the name adopted by the CC, or Catalan Community, following its definitive turn towards socialism in 1964) had taken part at a political seminar organised in Paris by the Trotskyite Jeunesse Communiste Révolutionnaire, involving Alain Krivine, who later became one of the icons of May 68, and Daniel Bensaïd.

These were contacts that, for the moment, served to reinforce home-grown Catalan dynamics of radicalisation, generated by a highly optimistic view of the scale and possibilities of mass mobilisation. This radicalisation ultimately led to an open confrontation between the PSUC student committee and the party rulers. A confrontation that culminated in a breakaway in April 1967, giving rise to what was known as the Unity Group, joined by a minority of militant workers, and ultimately taking on the name of the Communist Party of Spain (international). The aim of this PCE(i) was no longer to overthrow Franco’s regime so as to bring in a system of political freedoms, but directly to wage a socialist revolution. The internal split of the PSUC and the formation of the PCE(i) had a domino effect, accelerating the radicalisation of the FSF and prompting the radical shift that also occurred at the FOC (the Workers’ Front of Catalonia) from summer 1967 onwards.

PCE and PSUC: the maligned official communism

In the months that followed, up until Paris 68, there was in Catalonia a race to show which organisation was the most left-wing, which would succeed in becoming the chosen revolutionary party of the working class, defeating once and for all the “Carrillista revisionism” of the PSUC and the PCE. When the French PC and the CGT decided to call the social mobilisation to a halt, prepared to take part in the new elections that had been called, and to accept employment concessions, it took time for this incipient “revolutionary left” in Catalonia, which is how it viewed itself, to see its diagnosis and destiny confirmed. Nonetheless, until that point the impact of the May events in France was more one of ratification of their own action and reflection, than of innovation.

Innovation ultimately came, though, with the decline of Barcelona’s student mobilisation caused by the repression suffered by its leaders, the fact that many of the senior figures were nearing end of their university studies, and the growing doubts as to the possibility of maintaining an illegal, actively anti-Franco union, operating out in the open air. The innovative proposals for agitation and mobilisation in May 68, with their slogans, their insistence on cultural combat, the organisation of course committees, the occupation of teaching premises and the self-management of education, beginning with the debate as to the curricular programs, seemed a good alternative to the irreversible decline of the SDEUB. The appeal of novelty was further fuelled by the distribution of the works of Marcuse (Edicions 62 published a Catalan version of Eros and Civilisation in 1962) although the countercultural discourse of the university movement in Berkeley, predating May in France, had already been reported in Barcelona in the pages of the magazine Triunfo. The discourse of counterculture, youth emancipation, sexual freedom, added a new dimension to the personal relationships and anti-Franco militancy that extended its motivations beyond politics. The revolution acquired a subjective factor: the argument that it had to start within the individual.

During the 1968-1969 academic year, the FOC, the FSF, the PCE(i) and independent students, some of whom grouped together as the Union of Revolutionary Students, promoted the creation of action committees, the “occupation of professorships” with such high-profile events as the storming of the lectures by Prof. Palomeque, at the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, and Prof. Pifarré at the Economics Department, or the attempt to occupy the office of the Dean of Philosophy and Literature, whose incumbent, Dr Joan Maluquer de Motes, was defended by the students of the PSUC against the assault of the “leftists”. And here the impact of May 68 did finally arrive, an impact that ultimately in Catalonia was distinctly eclectic, with an accumulation of Althusserian Neo-Stalinism, Trotskyite and Maoist discourses and countercultural invocations, more or less Marcusian in tone, directed against bourgeois culture.