Centenaries should act as a stimulus to read the works of those they commemorate, and this is what we should do on the occasion of the 750th anniversary of Ramon Muntaner. But how should we read him? The fact is that we find ourselves before one of the greatest manipulators of our medieval past.

Photo: Prisma Archivo

The Arrival of Roger de Flor in Constantinople, oil painting by José Moreno Carbonero (1888), from the Palace of the Senate in Madrid, which shows almogàvers marching before the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II in 1303.

Centenaries: a way of creating literary and historical memory, over which we often have little control. After all, what should we do with those authors who have no proven date of birth or death, or for whom we have to wait too many years, or who, for some mysterious reason, history neglects despite their great importance? I am thinking of Bernat Desclot, for example, or Bernat Metge, possibly the greatest Catalan author of the middle ages.

One danger that lies in centenaries is the tendency to celebrate a national glory (real or imagined), often with no impact abroad, instead of using the opportunity to ask questions and to contemplate a historical panorama less, we could say, Catalano-centric or less academic, less like a foot note; instead of making a comparison with the present, leaving auto-victimisation and empty, self-indulgent triumphalism behind. At the very least, centenaries should serve as a stimulus for rereading the works of those they commemorate, and we should not merely content ourselves with attending some commemorative event or other. And so this is precisely what we should do on the occasion of the 750th anniversary of the birth of Ramon Muntaner. But how should we read him if, similarly to Ramon Llull, we find ourselves before a great manipulator, perhaps one of the greatest of our medieval past? I will not delve into Llull, as we are hardly on friendly terms, but rather I will speak of Muntaner, my relationship with whom involves much more dialogue. Ramon Muntaner offers us a great opportunity to analyse our collective past and its relationship with the present. An opportunity that would be all too easy to miss, unfortunately.

Muntaner crystallised (and it seems that he did so deliberately) the longings of the country, giving rise to a Christian/bourgeois/heroic vision of Catalonia, with little basis in reality, which stirred a desire for victories and international prominence. At the same time, he is treated by academia as if he were a completely neutral product. A curious and eloquent example of certain idiosyncrasies that are typical of this country, including academic asepticism. We can witness a fair number of contradictions, like that of a country which ends up celebrating defeats, while seeing itself reflected in a period of victories (only some of them, though). That of a country that wishes to be forevermore pacifistic, but also exalts episodes of extreme violence, like those led by the Almogavars. Finally, that of a country that rejected the monarchy many centuries ago, which was henceforth republican, but which, at the same time, delights in the falsest, most cloying and popular vision, almost like that of any gossip magazine, that its national literature has given of its monarchs. Is that what we want to continue thinking, both of the past and the future? Or would we prefer to know how it really was, as uncomfortable as that might be, and, most importantly, take responsibility for these contradictions?

The critics have painted Ramon Muntaner as a fighter and an adventurer, a middle-class son-turned-soldier, a good Catholic with patriotic sentiment, a good administrator and a man of heart, a faithful servant from a young age to all the possible kings born of the House of Barcelona; “one of the men most nobly characteristic of the land of Catalonia”, wrote Rafael Tasis in the 1960s. Is this really how he was? Who was he, in truth?

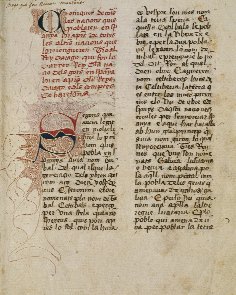

Photo: Prisma Archivo

First page of Muntaner’s Crònica, kept at the Episcopal Public Library in Barcelona.

Administrator of the Catalan Company

Born to a merchant in 1265 in Peralada, ultimately becoming a merchant and businessman himself, the contact Muntaner had at a young age with different monarchs (James I, Alfonso X of Castile, Philip III of France, Peter II of Aragon, James II of Majorca) made a great impact on his imagination, so much so that he formed an idealised and idyllic image of them. However, despite what has been written, he had no direct contact with any king until the last years of the century, when he was already an affluent man. His life changed dramatically in 1300 when he went to Sicily, which was then at war. There he met and befriended the pirate Roger de Flor, who he followed to Byzantium with the Catalan Company of mercenaries who were to enter the service of the Emperor. He occupied the post of the Company’s administrator, a position that allowed him to amass a fortune. It was in Anatolia where, forced by circumstances, he first discovered his taste for combat. In 1307 he decided to leave the Company, but it was not until 1315, when he was a married man with three children, that he gave up his wanderings around the Mediterranean and settled in Valencia. There he became a notable member of the city government and, from 1325 to 1328, he wrote the Crònica. During the last years of his life, as Mayor of Ibiza under James III of Majorca, his reputation was stained with accusations of prevarication, corruption and the pursuit of private interests while in public office. He died on the island in 1336.

A businessman (perhaps not the most scrupulous), an adventurer and a pirate, as well as a great writer, Muntaner narrated the most triumphant days of the Crown of Aragon. His chronical describes the conquests of Majorca, Valencia and Sicily, of Sardinia and the Catalan counties in Greece. These made a deep impression on his personal conscience (and on that of many 19th and 20th-century historians) and on how he saw his own place within history, which is why he needed to surround himself with monarchs in order to express himself. But with what values, with what ideas, with what vision of the world?

Journeys, comparisons and victories led him to become a passionate defender of his land – which we must consider more as the Catalan Countries than as Catalonia – and of his language. The union of the monarchs of the House of Barcelona, with the famous metaphor of the thicket of reeds, led them on to rule the world, just as the Tatars had done. He thus became the proponent of an aggressive expansionist policy that would lead to a global empire. A medieval Catalan empire, not so extensive, whose vestiges remain in popular culture and, still, in a section of academia. All of this, however, at the cost of a lack of curiosity for anything foreign, and with a strong sense of hostility bordering on xenophobia for anything that was not Catalan or was the enemy of Catalonia.

The past, a mirror or a tool for understanding

Muntaner was not simply a good Christian but also a fundamentalist. The God who appears in his chronicle is not the merciful God who protects the good, but the vengeful God of the Old Testament who protects the chosen people (the Catalans) and strikes down all their enemies in rage, specifically the enemies of the kings of Aragon and of Muntaner himself. That is why he adapts, manipulates and lies about the history of Catalonia to paint a politically correct portrait full of good people, where his flair for narrative always takes precedence over the facts.

Are these the characteristics of the Catalan nation of which Tasis spoke? Or perhaps we have other characteristics, and we must simply accept that we have changed over the centuries, that the past is not a mirror but rather a tool for understanding? We should not fool ourselves, nor let ourselves be fooled. We must bear all of this in mind when reading the Crònica, without it detracting from the pleasure of reading the book. A pleasure which has attracted readers precisely for this sense of victory and superiority, for having left the confines of the Crown of Aragon and the peninsula to travel across the Mediterranean, for its colloquial and conversational tone, for the thrill of adventure. All of this, to a great extent, invented by the writer, who is perhaps more novelist than historian.