Maybe the stories zigzag around Poble-sec and mutate each year and in every square. Or maybe they emerge from the Paral·lel, that avenue of light and showbiz that was given its name by an astronomer and a wine seller.

No-one wants to know where the rhythm comes from, just who is bringing it.

In this neighbourhood, there are many suspects and few clues. I’ve been looking for them since I was little. I stumble across traces, but the mystery escapes me. I’d watch the Mama Chicho showgirls on TV, unaware that those bikini-clad ladies from another planet were ruining business at El Molino cabaret, five minutes from my house. I’d listen to stories laced with the smell of fish brine and fresh fruit in the market. Sundays were spent at the flea market where the best books cost less. At first I’d go to swap collectible cards, then to buy copies of Tintin, and later to discover novels. After that, I even wanted to write them myself.

Sant Antoni is an arrow, shaped almost like a musical triangle, the instrument that is the cherry on the cake in an orchestra. Its edges vibrate along Gran Via, Paral·lel and the Rondes, while inside the rhythm explodes. Posters at the fruit stalls advertise twins with hairpieces and guitars. People clapping rhythmic flamenco beats do the rounds at the outdoor cafés; wasps buzzing around the beers and the wallets.

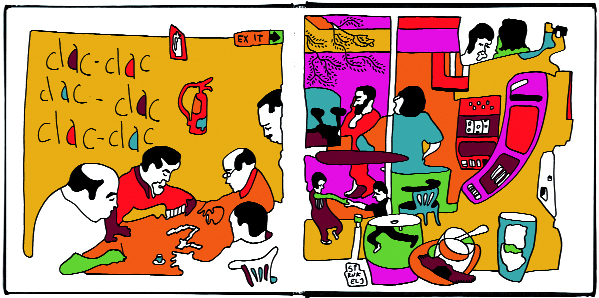

The woman who gave away fritters in the market used to tell a story about La Maña: the cabaret star of the Paral·lel used to sunbathe with the solarium roof closed (she never got tanned). There’s another story about the gypsy on Carrer de la Cera who wasn’t a gypsy at all: he’d once heard the rumba singer and pianist El Chacho and decided he wanted to be like him, so he sprayed himself in fake tan, greased his hair with brilliantine, hung some gold around his neck and started a rumba band. Now everyone says he’s a gypsy, although everyone knows he isn’t really, but that’s what’s so funny about it and the story is definitely worth a smile and a raised glass and a song. Catalan rumba legend Peret was at the slot machine in Els Tres Tombs so early one Monday morning that no-one knew quite whether he was on his way out or on his way home. They say that he was bankrupted by the Evangelical church, paying for too many palms and wafers.

Maybe the stories zigzag around the alleyways of Poble-sec and mutate with every year that passes and in every square they pass through until they get to the market, ready to be read. Or maybe they emerge from El Paral·lel, that avenue of light and showbiz that was given its name by an astronomer and a wine seller. Maybe they come from El Raval, travelling up Carrer de la Cera looking for some no hoper from L’Eixample who wants to believe them, who can write them down, who can’t forget them.

Where did all this rhythm come from? From the copla folk music theatres on the avenue, the streets where the Catalan Rumba came to life, the slow-dance halls on Gran Via or from Carrer Aldana where the rockers would rehearse? What matters is not where the rhythm came from, but who brought it here.

Here, where I am now. Right behind Els Tres Tombs restaurant, O Barquiño, the bar where many things come to pass but what never passes is time. The rhythm is carried by a slot machine, with its shaky chatter and its fruits and bells all in a line. It is marked, clack, by the dominos, clack, on the Formica tables with their clack-clack-clack. And it also comes down the stairs from a first floor where the ceiling is low and the spirits are high. Twenty regulars scoffing octopus and ham, helped along by chateau plonk served in a tumbler. Photographs hang on the wall of the same people as are here now, but thirty years younger. They’re not waiting for an artist to come, because they’re all artists.

A man with a strongman moustache and chipmunk cheeks, who organises the ruckus and who probably painted these walls, because as well as an artist he’s a painter decorator, sings a rendition of Trasnochador. There’s also applause for El Colorines, with his rainbow shawls and his ruined boater, a character who doesn’t “sing for the sake of singing” and who, as well as singing, also repairs TV sets. And Antonio Linares and El Romántico and even Pilar Carrión come out to perform (with no airs and graces) without asking for money or permission, supported by the inertia of a neighbourhood that doesn’t exist.

Good stories are like gold teeth. Sometimes they survive in ruined mouths and cover gaps and shine in the night and appear when someone smiles.

Where does all this rhythm come from? None of them know. What matters is not where the rhythm comes from, but who brings it. And who knows how to keep it going.