In that time, for me not having papers used to mean (means) lacking facts. But there was nothing to fear in the library.

I was lucky enough to live in Carrer de la Riereta for several months. El Raval has that certain type of suburban atmosphere synonymous with other large ports I’ve had the opportunity to live in. There, I felt at home and in my place in the world. Or rather, my home was confused with the world. It had the protected vulnerability of crossroads, dramas and stories. Maybe it was because I spent my childhood in a poor neighbourhood. Living among diversity is a joy and I suppose that only in diversity do similarities emerge. As such, I felt happy during those few months among natives and travellers arriving from distant places. The old building (19th century?) had thick, damp walls and winding stairs. I liked the coffered ceiling, the pull-down window in the bedroom, the small window that opened out onto a blackened-rooftop pattern, like in a canvas by Braque. I used to enjoy the smells of foods that were beginning to arrive from different places: a single, foreign scent that, in my imagination, was straight out of A Thousand and One Nights. The distant cries of children, the sounds of bachata, and someone clumsily practising on the piano over and over, combined to make the silence even more intense. Being from Havana, silence astounds me like a prodigy; I long for it like you would a miracle. Even more so when I used to associate it with thick, old walls that spoke of a time when Cuba did not even belong to the “known world” in the West. Silence and antiquity are enigmas to someone from Havana. A building that predates the 18th century plunges us into perplexity, into melancholia.

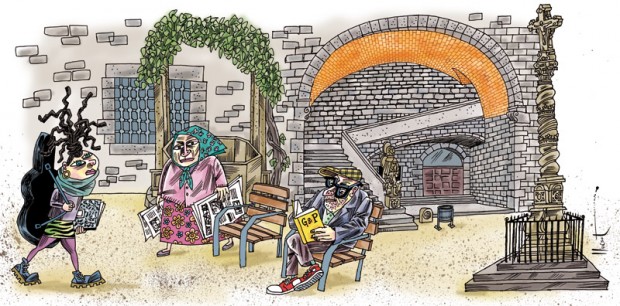

I was walking along Carrer de l’Hospital and I arrived at the National Library of Catalunya (BC) with the feeling that I had transcended the small space and time that had been given to me. It is difficult to explain the shudder of someone who has to recall an impossible time. The extraordinary library had been a hospital. It was continuing its purpose to save lives. Its walls had begun to be built before Columbus’s three ships had set sail towards the wrong Indies. I knew it was protecting me. During those years I was undocumented. “Not having papers” used to mean (means) lacking facts. I had, let’s say, the dubious “advantage” of being white with blue eyes: I met the “parameters” of being a man who was “one of ours”, decent and inoffensive. If I didn’t speak, I could camouflage myself. If I lowered my gaze, I became invisible. However, knowing that your passport and visa have expired can make you feel like a tightrope walker without the talent and balance for the ropes. But there was nothing to fear in the library. Paradise in the form of a library, as Jorge Luis Borges would say. Neither was there anything to fear in the gardens of the old hospital. We were all the same. Beaming students and honourable beggars. Whether joyful or resolutely sad, the garden did not lose its hospitable virtue.

When I wasn’t reading, one of my greatest passions consisted in imagining the lives of strangers. Where had the Moroccan-looking boy come from? And for what designs had the Romanian-looking lady with the scarf finished picking up some newspapers only to sit down in the gallery? We weren’t all foreigners. A very pale young man was sleeping on a bench and, the times when he was awake, he spoke in Catalan. “He’s from Igualada”, announced a girl with dreadlocks from Berga. I was sat next to an old man who was reading. His book, to my surprise, was Gargantua and Pantagruel. I would have expected him to have been reading Isis Unveiled; so rarely are our prejudices borne out. He would look up occasionally, like someone surfacing to check that the Earth was still turning. I felt like just another down-and-out, but I wasn’t one. Even “without papers”, a small apartment in a building on Riereta was waiting for me; the walls would shelter me from the climate. I would be able to shower, eat some soup and have a bed with sheets. I would lie down and feel a jolt at the realisation of being in the centre of the world. Barcelona would be the centre of the world, and the down-and-out reader of Rabelais, the prophet of an enthusiastic outsider.