These days, not even the neighbourhood’s own mother would recognize it. Still, it’s worth saying that the change has been for the better.

“For folks from the shacks, those girls are pretty well-dressed”, noted a group of women in Arenys de Mar in a voice loud enough for our class of nine-year-old girls to hear as we filed past under the standard of the nun’s school of El Poblenou in Barcelona.

It was the fall of 1959. The Missionary Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, a sub-order of the Franciscans, were celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the school with a series of events in Arenys. It was the home town of their founder, Anna Maria Ravell, a teacher who became a nun and is currently in the process of being beatified. There I was, behind my school’s standard, in uniform just like my classmates: a woollen houndstooth dress, brilliant, patent-leather shoes and bright-white socks. Nothing to do with the kids from the shacks. Ours was the preppiest school in the neighbourhood. Unlike the apartment schools, we had a playground.

Of course, there were shacks in El Poblenou back then. There were some on the beach, some behind the old cemetery, some in Bogatell… I would see the kids from the shacks in El Somorrostro when they would catch the 36 tram, which went up and down Avinguda Icària. It would always stop for a while at the railroad crossing, and some of the mothers would seize the opportunity to loosen their corsets and let their infants nurse. But the kids from the shacks weren’t scary. They were as clever as foxes. I did feel sorry for –and was a little scared of– the kids from La Prote (the residence for the Protection of Minors), who wore striped smocks and had their heads shaved (to keep the lice off, I suppose). They went to my church, Sant Francesc d’Assís, where they served as altar boys. Their bald heads emphasized the mournful look in their eyes.

25 years after Arenys, in 1984, I tried to sell my flat in El Poblenou and move back to the house I was born in, but the realtors didn’t want it: “we don’t operate in that neighbourhood”, they said with disdain. Now they would take it in the blink of an eye, and if the ladies who though I was from the shacks could see my grandchildren, all well-dressed and blond, they would say that they look like kids from La Vila Olímpica.

With La Vila Olímpica –the Olympic Village– things started to change. There was an earlier project, the Pla de la Ribera or Costal Plan (1965-1968), promoted by Mayor Josep Maria de Porcioles. It aimed to wipe El Poblenou and its inhabitants off the map, and turn the area into the kind of Copacabana the mayor dreamed of. It ended up being filed away, but only after plenty of businesses decided to move out of the city and abandon their lots. This plan, which was defeated by a rising citizens’ movement that turned in a record number of objections, included the collaboration of Narcís Serra and Miquel Roca Junyent. Twenty years later, the promoters of the Olympic project found their work had largely been done for them: most of the lots were empty and just had to be purchased. Some landowners, like Carles Ferrer Salat, demanded more than the City Council had been expecting. Others, like the Folch family, were excluded from the plan at the behest of the king, which allowed them to sell their property at a later date and at an exorbitant cost. The Olympics helped us to recuperate our city’s coastline, the train tracks were torn up and the coastal highway was put underground. Barcelona won its nicest playground.

After the Olympics came the still-hard-to-understand Forum debacle, which did help to start stitching up the abyss between Barcelona and Sant Adrià with the development of the areas now known as Front Marítim and Diagonal Mar. Still, these projects weren’t as social as the Vila Olímpica, and once again real-estate speculation dominated.

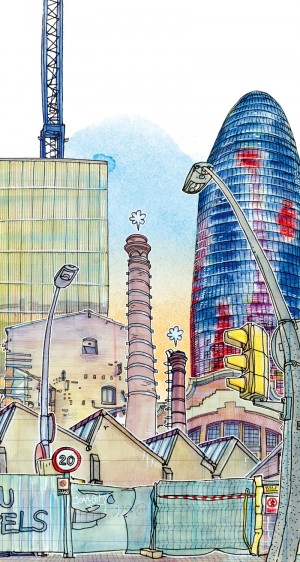

The final touch was the never-ending 22@ project, which at the very least freed up some old industrial buildings. Some have become monumental public facilities. However, the one-two punch of the economic recession and the reduction in municipal investment have left the project on standby.

Now, not even El Poblenou’s own mother would recognize it. Still, it’s worth saying that the change has been for the better. We’ve gone from being the tail end of the city to the most sought-after area, where life-long neighbours are driven out, especially by the skyrocketing rents. It’s trends. It’s gentrification.