When Franco’s forces crossed the River Ebro, everyone believed that the Civil War was lost. In accordance with the scorched earth policy ordered by Moscow, the Communists decided to destroy everything that was still under their control. In Barcelona they planned to blow up factories, roads, underground train tunnels, energy supply points and drinking water pipes. The city was saved at the eleventh hour because the plan was sabotaged by the leader who was supposed to carry it out, Miquel Serra i Pàmies.

During the Spanish Civil War, the USSR and the Communist International sent many resources and some of their best men to Spain in an attempt to control the development of the conflict and thus achieve a communist satellite in the south of Europe. The USSR was worried about Adolph Hitler’s rapid rise, and gaining a trusted ally in Western Europe was of vital importance.

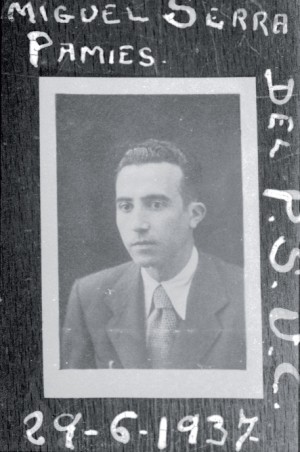

© Josep M. Sagarra / ANC

Reproduction of a portrait of Serra i Pàmies belonging to the collection of photographer Josep M. Sagarra, held at the National Archive of Catalonia. The date recorded is that of the presentation of the Companys government, in which the young PSUC leader served as Minister of Procurement.

The Communist Party of Spain (PCE) was already under the control of the Comintern, which afforded the latter a strong influence over the government of the Republic. However, the political situation was more complex in Catalonia, making it much more difficult for the Comintern to exercise any influence. Furthermore, Moscow observed, with concern, the increasing influence of the POUM (the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification) and the CNT-FAI (the National Confederation of Labour-Iberian Anarchist Federation), organisations which were totally alien to the Soviet ideology. On 23 July 1936, political events seemed to take a turn in favour of Soviet interests. The Catalan Communist Party, the Socialist Union of Catalonia (USC), the Proletarian Catalan Party and the Catalan branch of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party joined up to form the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC). This new party fulfilled the main ideological lines of the Communist International, which immediately tried to turn it into a regional branch of the PCE to ultimately achieve some kind of influence in Catalan politics. The leaders of the USC included Miquel Serra i Pàmies, born on 17 January 1902 in Reus. He was a founding member of the PSUC, as well as its vice-secretary and treasurer. His marked Catalan nationalist ideology and strong social commitment prompted President Companys to appoint him Minister for Supplies on 29 July 1937. His portfolio of responsibilities grew in the course of the Civil War, and he also became Minister for Public Works.

Several PSUC members, led by Serra i Pàmies, opposed the idea of the party losing its independence and taking orders from Moscow, while being under the leadership of the PCE appealed to them even less. The ideal of the Spanish Communists was a centralised Spain where Catalonia was simply a region that needed to be incorporated into the whole. This clashed head-on with the Catalan nationalist spirit and the desire for political independence forged by the PSUC.

However, as the war progressed, nervousness spiralled among Republican politicians. Some members of the PSUC began to put the survival of the party before the survival of its founding ideals. They wanted to yield to the pretensions of the Comintern and the PCE, in a desperate attempt to secure foreign support and resources for the PSUC to survive in exile once Catalonia fell to the Nationalists. Despite growing pressure from within the party, Serra i Pàmies was unswerving in his defence of the PSUC’s independence from the PCE. This attitude infuriated the agents sent by the USSR and the Communist International to Spain to subjugate the Catalan party. Different reports reached Moscow, describing Serra i Pàmies as a dangerous element for achieving communist goals in Catalonia.

The Comintern orders the city to be razed

After Franco’s troops crossed the River Ebro, everyone regarded the Civil War as lost. The highest-ranking Republican political leaders began to head into exile, although Barcelona was already preparing a staunch defence. Every morning, lorryloads of people, young and old, went out to dig trenches. The political and military leaders soon realised that the population, discouraged and exhausted from lack of food, would not rally to the calls for resistance made by the president of the Spanish government, Negrín. At this point, events took a dramatic turn. Blinded by rage and by their slogans of “victory or death”, the Communists decided to destroy anything they could not control. The orders from Moscow were clear: scorched earth.

A meeting was convened between members of the PCE, the PSUC and demolition experts of the Lister Brigade to execute the plans of the Communist International and the Soviet Union. The plan to destroy Barcelona was drawn up at this meeting. They had a few thousand tons of TNT and large amounts of artillery ammunition, enough to blow up the city’s main factories, energy supply points, drinking water pipes, roads and underground train tunnels. It was estimated that a quarter of Barcelona would be destroyed, while calculations were made as to the hundreds of deaths that would be caused by the explosions. They concluded that it was acceptable collateral damage. None of the participants at the meeting dared to question the plans submitted by the Comintern agents. Realising that all opposition would be futile, Serra i Pàmies offered to take care of the final details and issue the fateful order to destroy Barcelona. However, far from carrying out the task, he did his utmost to thwart such a monstrous project. He constantly called meetings, creating confusion as to the times and places, gave out wrong contacts and made up all kinds of delays. Barcelona remained intact as long as he put his life on the line. It was a race against the clock, as he anxiously awaited the entry of the Nationalists into Barcelona before his sabotage could be discovered.

On 25 January 1939, the government of the Republic and the government of Catalonia had already left for France. The anti-aircraft batteries of Montjuïc had been dismantled and the ministries and other offices had been evacuated. There were still some PCE and PSUC members in the Ritz Hotel, but when they learned that Franco’s troops were advancing towards Pedralbes, they quickly shut up shop and took the road to exile.

The two remaining members of the PCE in the room asked the PSUC members to go on ahead of them, saying that they had a matter to deal with. On hearing this, Miquel took Abelard Tona i Nadalmai aside, asking him to stay with him and not to leave the room. Abelard immediately understood why his friend and party comrade was asking him to stay in Barcelona, despite the mortal danger this entailed. The two PCE members had been ordered not to abandon the city until the last PSUC member had left. They would thus be able to report the PSUC to the high-ranking members in Moscow for an act of cowardice and betrayal in surrendering Barcelona to Franco and then use it as a pretext to call for the dissolution of the Catalan Party.

© Brangulí / ANC

Foto oficial del govern format per Lluís Companys el juny de 1937. Serra i Pàmies hi apareix dret, el primer a l’esquerra.

The two PCE members and the two PSUC members spent the night in Barcelona, nervously waiting for one of them to decide to take the first step towards exile. The impasse was broken on the afternoon of 26 January, when a waiter entered the room shouting that Franco’s troops were marching along Passeig de Gràcia – the Ritz Hotel was only a couple of blocks away. They all jumped up at once and made for their cars. It no longer mattered who left first, their sole aim was to avoid being captured by the enemy.

Serra i Pàmies managed to escape from Barcelona by car and headed for the French border. Finally, thanks to his delaying strategy, Barcelona remained intact. Franco’s troops were greatly surprised to discover that the civil engineering structures and most of the factories were still in working condition. Their intelligence reports had predicted that the Communists would apply the scorched earth policy.

From France to Stalin’s prisons

Once in France, Miquel Serra i Pàmies was reunited with his wife, Teresa Puig i Sitges, who had left Barcelona a few days before him. First they settled in Paris, but things were not peaceful in exile either. The French secret service watched the Catalan and Spanish political leaders’ every move. Franco’s secret service also began to pursue political exiles. This obliged the couple to move to Orleans, where they would be a little safer.

Joan Comorera travelled to Moscow in May 1939 to meet the Comintern. The PSUC’s General Secretary wanted the Catalan party to be recognised as a member of the Communist International. After tough meetings, and against all odds, Comorera managed to get the Comintern to accept the PSUC as a new fully fledged member, making an exception to its centralist principle. This decision obviously incensed the leaders of the PCE. Furious at having missed an opportunity to get rid of the Catalan party, they decided to make those who had stood up to them pay dearly.

In July 1939, Joan Comorera asked Miquel Serra i Pàmies and Josep del Barrio, another PSUC leader, to travel to Moscow. He told them that the Comintern wanted them to attend as party representatives to complete their accession to the Communist International. Although the General Secretary told them that it was a mere formality and that they would be back home in a few weeks, Serra i Pàmies wrote some letters to friends by way of farewell. He knew full well that he might never return from Moscow.

When the two party comrades reached the Soviet capital they were arrested. Miquel Serra i Pàmies was taken to Lubyanka prison, like Bukharin, Zinoviev, Radek and many other socialist and communist victims of Stalinist purges before him. While he awaited a trial whose outcome had already been decided, Serra i Pàmies was subjected to brutal interrogations and torture in the freezing basement of the headquarters of the NKVD, the Stalinist secret services.

The Moscow trial

The trial commenced on 14 August 1939. The jury included high-ranking members of the Comintern secretariat, such as Georgi Dimitrov, the future head of the government of Bulgaria, Vasil Kolarov, future president of the Bulgarian Republic, Wilhelm Pieck, future president of the German Democratic Republic, and Ernö Gerö, a Soviet agent operating in Spain. Other participants included La Pasionaria, Jesús Hernández and José Díaz, high-ranking members of the PCE and the trial instigators. Miquel Serra i Pàmies was accused of several offences, some of them beggaring belief. Sitting on the dock, Serra was accused of being anti-Communist, Trotskyist, responsible for losing the PSUC’s files, a Freemason, refusing to carry out the order to blow up Barcelona, responsible for losing the PSUC’s funds, being a member of the French secret service, and finally of being the main culprit of the loss of the Spanish Civil War. On hearing the last, and utterly ridiculous accusation, Miquel Serra i Pàmies, weakened by the torture to which he had been subjected, suffered a nervous breakdown and the trial had to be adjourned. The effects of this attack were permanent, in the form of paralysis of the right half of his face.

In subsequent sessions, Pàmies was given the chance to defend himself. He knew that there was nothing he could say to change a sentence that had already been issued before he reached Moscow. Nevertheless, he decided to face up to the accusations, arguing, for more than three consecutive hours, why he had boycotted the strategy of reducing Barcelona to ashes. His defence was so moving that the jury decided to consult directly with Stalin. Finally, the Comintern found that razing Barcelona would have constituted a massacre of civilians that would have been repudiated by the rest of the world, seriously damaging the image of communism.

The trial ended on 20 August 1939. Miquel Serra i Pàmies was cleared of having violated the order to blow up Barcelona, but was convicted of the other charges, including being the main culprit for losing the war. His comrade, Jose del Barrio, was also convicted, albeit of less serious offences.

When the sentence was passed, the two party comrades were utterly baffled. They were ordered to travel to Chile to create the PSUC in exile. They could not explain how this mission could be entrusted to two people guilty of so many crimes against the communist cause, although they were soon to understand what was afoot. The route the Comintern had prepared to take them to Chile began on a train bound for Siberia. As soon as they could, the Catalans outwitted the two secret agents who were watching them and jumped train. After a long, difficult journey they reached Vladivostok, the USSR’s easternmost port. From there they headed to Japan, where they took a boat to Los Angeles. They traversed the American continent to Chile, where several friends and members of the PSUC had already gone into exile. However, Miquel Serra i Pàmies feared that his life was in danger there and decided to retrace his steps, settling in Mexico, where there was also a large colony of exiles.

Exile in Mexico

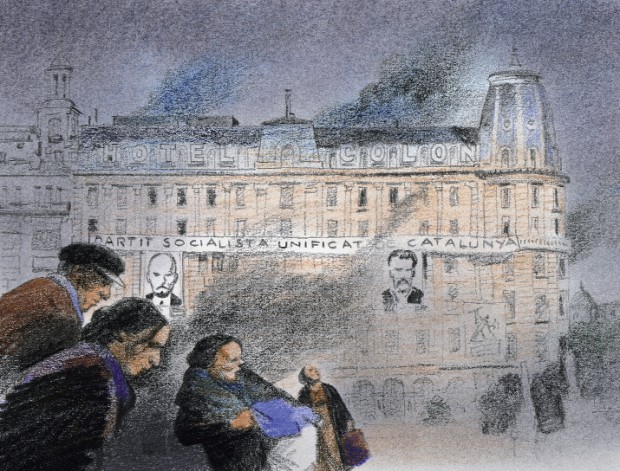

© Pérez de Rozas / AFB

The Hotel Colón, on Plaça de Catalunya, where the PSUC set up its headquarters, in an image from November 1936.

Shortly after Miquel left for Moscow, Teresa received a letter from the Soviet capital telling her that her husband had died heroically, fighting for the communist cause. Serra i Pàmies also believed that his wife and his daughter, whom he had never met, were dead. He had read in a newspaper that a German bomb had hit the air-raid shelter in the French district where they lived, causing a huge number of casualties. However, despite adversity, all three of them were still alive, and thanks to the Red Cross refugee family reunification programme the family was able to make contact again. Nonetheless, being reunited would be no easy task – Franco’s secret services prevented Teresa and her daughter from taking a boat from France to America on up to six occasions. They were trailing them in the hope that Miquel Serra i Pàmies would return to France to look for them, where they would arrest him and bring him to trial. They eventually obtained false papers that allowed them to sail from France to New York. From there they took a bus to Mexico, where they were reunited with Miquel Serra i Pàmies. The family moved to Guadalajara, where their grandchildren and great-grandchildren live to this day.

Serra i Pàmies wrote a letter to his brother from Mexico, which reads: “Do you think if the people of Barcelona knew about all this they would show me some kind of gratitude? I, who could have died in Barcelona through my delays and counter-orders, and later in Moscow, in the trial. Do you think that one of the citizens for whom certain death awaited would have thanked me? No, brother Josep. People forget about dangers past and live for the present. If they ever remember anything, then it is the barbaric, rather than the human, deeds […] In my opinion, no one can say they have fulfilled their duty, either as a Catalan or as a public person. We are all, each and every last one of us, responsible for our nation’s tragedy. The only thing I could prove is that I was not a coward.”

Miquel Serra i Pàmies never returned to Barcelona. He spent the rest of his life in Mexico, where he died of pneumonia on 14 June 1968, at the age of 66. His story was never told. Even today, very few people know how close Barcelona was to being razed to the ground. How difficult would the post-war period have been in a Barcelona devoid of electricity, drinking water and an industrial fabric? What would Catalonia be like today if its capital had been reduced to rubble? These grim questions will go unanswered forever, thanks to the efforts of a man we forgot.

M’ha posat la pell de gallina. Gràcies per fer justícia a un veritable heroi. Ara caldria fer-ne més difusió i posar remei a aquest oblit imperdonable també des de l’àmbit institucional.

Que caldria fer per dedicar no un carrer ni una plaça sino tot un monument (i dels que fa goig) en un lloc centric de la ciutat que va salvar? Per quan el reconeixement que es mereix aquest heroi?

Us imagineu si s’hagues fet? Que haiuriem reconstruit els franquistes? Res! On seriem a hores d’ara? Una ciutat de 4a categoria… Sense vida ni industria ni tants habitants com ara…

Es podria parlar amb tv3 perque en facin un documental que ens acosti aquesta figura a tots?

Pell de Gallina.

Aquest home si que es mereix un nom a un carrer i no en Samaranch. Son la nit i el dia.

Pingback: L’home que va evitar la destrucció de Barcelona | Núvol

Desconeixia ,com molta altra gent, aquest autèntic heroi de Catalunya.

N’ha ha per fer-ne una pel.lícula . No sé per què alguns s’entesten encara en no reconèixer Stalin com el más gran assassí de la història d’Europa , a la mateixa alçada de Hitler i Franco sens dubte.

Els comunistes de Negrín volien fer-li la feina bruta als franquistes tot destruïnt Barcelona i Catalunya ,tal i com volia haver fet la FAI dos anys abans.

“Pobra Catalunya , crucificada com el Crist entre dos lladres ” com preclarament havia escrit el gran escriptor Joan Sales , que va viure en primera persona els crims de tots els totalitarismes que volien cruspir-se el nostre país.

Completament d’acord amb tot. És mereix un gran monument i una pel.lícula.

Puc donar testimoniate d’una cas que guarda similitud. El meu avi, Miquel Gisbert Albertos, comissari de la CNT del parc d’artilleria de l’exècit de l’Ebre, tenia ordre d’Enrique Líster (PC) de volar, en la retirada, les caves Codorniu que havia servit d’infraestructura d’artilleria i on es guardaven peces, principalment en reparació. Miquel i els seus es van negar, perquè consideraven que les insta·lacions no eren estratègiques per garantir la retirada i perquè la població de Sant Sadurní no s’ho mereixia. Quan a Figueres, Líster se n’assabenta i condemana a mort el comissari i envia un escamot, quan la es trobaven prop de la frontera. Després d’auntar-se uns i altres, i danvant la situació, de pas immediat a l’exili, l’escamot comunista es va retirar.

Es clar que aquest patriota mereix un carrer o un monumennt!.

Peró pel que sembla, i per motius diversos, tan ell com el Samaranch esperaven amb candaletes l’ entrada dels nacionals per la diagonal… paradoxes de la vida, ja diuen allò de “los extremos…”) Franco i Stalin (com molts anys més tard varem descobrir) no eren pas “blat net” i els dos van ser o “eran”, un perill per Barcelona, el que passsa es que el segon perill s’ ha amagat massa., segurament perque el nostre heroi ho va evitar.

voldria saber la llista dels 200 noms pendents d’assignar carrer. No voldria que es poses nom a persones de dubtosa moralitat, per molts altres merits que pugui tenir, i quedessin sense els dignes, com aquest. Si no, al final, pagant t’assignaran un nom, qui sap si per uns anys, i així anar fent i anar ingresant diners. El nomenclator pot tenir funció pedagògica.

Tantes històries ens amaguen…!Entre els uns i els altres. Ens amaguen , menteixen i difamen la nostra HISTÒRIA.Molt sovint per interés, quasi sempre, a més per ignorància i també perquè, a vegades, alguns viuen bé instal.lats en l’autoengany Sembla que la situació límit en que estem ara al païs, ha fet obrir els ulls, l’interés, la intel.ligència i la consciència per saber la veritat,les veritats de la Història, de la economía i la política que ens mena.

Llàstima que hagi sigut al preu de tanta devastació que haguem escoltat la veu dels savis i dels honrats de la nostra Terra.

Caldria fer córrer aquest article i tota la informació que dóna perquè arribés a l’ajuntament i a qui correspongui fer justícia.

I, certament, seria trist que el franquista Samaranch tingués un carrer a la ciutat i l’home que la va salvar del desastre arriscant la vida fos ignorat.

Que gran!

Von Choltiz, Paris, 1944.

Una prova més de com la guerra del 36 va ser una guerra declarada Espanya contra Catalunya, i els quintacolumnistes de la FAI perfectament equipats i dirigits pel govern republicà espanyol. I hom em contava: els republicans espanyols mataven catalans, i després el franquistes espanyols mataren més catalans.

Dir que la guerra de 1936-39 és una guerra d´Espanya contra Catalunya, Gustau, suposa, a banda d´una mentida grossa i una barbaritat, escopir sobre les tumbes dels combatents republicans a Terol, l´Ebre, Guadalajara i tants i tants llocs, que lluitaven contra el feixisme que pretenia destrossar la legalitat (que incloia l´Estatut de Núria) republicana.

És a dir, dir això és una salvatjada. ¿Cal recordar que hi havia castellans franquistes i no franquistes, i catalans franquistes i no franquistes? Sisplau, mentides en assumptes tan seriosos, no!!

Com he sigut censurat en una resposta anterior a Gustau, ho diré amb altres paraules:

El que afirma este home és directament MENTIDA. La guerra va ser entre esquerres i dretes, no entre castellans i catalans. Va haver franquistes castellans i catalans, i també esquerrans. I dir el que diu Gustau es escopir sobre les tombes dels republicans morts al Jarama, Terol, Guadarrama i l’Ebre.

Perdona, sí t’he ofès, però hauries de saber llegir i distingir entre govern i el poble que està governat. El govern espanyol republicà sí que va declarar (no obertament) la guerra a Catalunya i els catalans.

Has de pensar que el colp d’estat va estar permès i el govern espanyol republicà era assabentat. El colp d’estat en un principi era només un efecte militar per a frenar la Generalitat de Catalunya que a poc a poc tenien més clar que el camí era la Independència, i per altra banda al País Valencià i al País Mallorquí, Galícia creixia l’anhel per obtenir també la federació.

Poc es pensava el govern espanyol que el poble català i d’altres ciutats, els moviments populars van saber defensar-se. I a més a més, hem de pensar que els colpistes espanyols, dirigits per la dreta tradicional espanyola volien enderrocar la república per tornar al vell règim que tant agrada en Espanya.

Perdona,s i t’he ofès, resulta, però jo no m’empasse el mite romàntic de la República espanyola.

Artur, estic amb vosté. Assistim a una reinterpretació històrica preocupant.

Gustau, aixó que dius es una barbaritat. Em demano què et van ensenyar a l’escola. Si us plau, llegeix història o llibres, qualsevol.

El nacionalisme feixista espanyol ultra-catòlic i la república española anti-cristiana podien tenir moltes diferencies ideològiques però tenien una cosa en comú: un marcat nacionalisme español. En aixó ho tenien claríssim.

Vàren venir primer els escamots anarquistes españols als pobles catalans dient: “SI HABLAN CATALÁN, SON BURGESES, fusilaremos a unos cuantos y les robaremos.”

Després varen venir els feixistes als pobles catalans i van dir: “SI HABLAN CATALÁN, SON ROJOS y SEPARATISTAS fusilaremos a unos cuantos y les robaremos.”

La república española es una falàcia.

Rectifico: no vaig ser censurat.

Quina por fa tot plegat, quin patiment van tenir tota la família i que emocionant el retrobament a Mèxic,

Que malament els del PCE, quina barra !!

Me gustaria saber, este que se encotro en Mijico, co la familia si sabe algo del Barco, Evita, que se lo llebaron, creo entre Asaña y Negrin, cargado de joyas y alajas quie se que do con el espero que alguien sepa algo y cuente esta azaña de la guera civil.

Una història bonica. Enfrontant-se a uns i altres va demostrar molt de valor i estima pel seu país. Caldria difondre-la i que la gent conegués millor fets com aquests.

!!Me ha encantado.!!

Desconocía esta historia de tanta valentía y tanto heroísmo

!!Gracias y mas Gracias!! Miquel Serra i Pamies

Por haber salvado Barcelona

Aquest home mereix un documental a TV3 el més exhaustiu i imparcial possible

El menys que puc fer és donar les gràcies a un home tan valent i amb tan sentit comú, jo tinc molts anys i no coneixia la historia. Gràcies Miquel Serra I Pàmies

La desmemòria és vasta i mai és innocent, és més còmode silenciar la figura de Miquel Serra i Pàmies que no pas fer-la pública, perquè mostra els clarobscurs i les complexitats de la guerra civil i de la política internacional de la seva època, una història on no tot és blanc o negre. És colpidor com el mateix Serra i Pàmies és conscient que no serà recordat ni honorat, ja que es recorden “les gestes bàrbares, no les humanes” . Tota una lliçó sobre la història i la naturalesa humana.

Pingback: Miquel Serra i Pàmies, quan Barcelona va estar a punt d’esclatar | Tras las huellas de Heródoto

Quanta injustícia!. Es mereix ser recordat amb agraïment.

No debemos olvidar NUNCA a estas personas valientes no importa de que ideologia son. Debemos siempre tener orgullo de los españoles valientes., que los hay y mucho! Estos son los nombres para nombrar nuestras calles y plazas!

Pingback: “Miquel Serra i Pàmies, l’heroi oblidat de 1939. L’home que va evitar la destrucció de Barcelona”, per Guillem Martí | Lliure i Millor

Pingback: Guillem Martí: 'Se'n va sortir i va salvar la ciutat' ⋆ Noticias de hoy

El que podeu fer és comprar el llibre

“Cremeu Barcelona! ” d’en Guillem Martí

Que explica la història d’en Miquel Serra i Pàmies.

Jo l’he llegit en 2 dies. Explica aquests fets molt bé

També crec imprescindible llegir “Fou un guerra contra tots” de Josep Serra i Pàmies, germà d’en Miquel.

Gràcies per l’articlesl’article, que da nemòria històrica i un exemple d’èrica. Gràcies Miquel Serra i Pàmies

se han preguntado alguna vez como le fue posible no cumplir las ordenes de destrucción.

¿ quien fué el capitán de ingenieros que, jugándose la vida, apoyó y tapó al Señor Serra? todo bajo la atenta mirada del temido Lazarev, qué pasó con el capitán que colocó cargas que no estallaron nunca?

el sr. Martí en su libro indica que en la reunión en la que estaba el ruso, había un militar, capitán de ingenieros, quien, jugándose la vida, apoyó y consiguió engañar al temido ruso para poder llevar a cabo el plan, no destruir Barcelona.

esta es una historia que no se ha contado nunca, no se por qué ha incomodado a mucha gente que, hasta ahora, nadie había indicado la verdad, los que la llevaron acabo el s_r. Serra y el capitán de ingenieros no quisieron que trascendiera, los dos pagaron después su desobediencia.

I si comencessim una petició a change.org perquè li dediquessin un espai a Barcelona?