Three hundred years have transpired since the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), putting an end to the international dimension of the War of the Spanish Succession. This commemoration offers a golden opportunity to reflect on the British position in the dynastic conflict through the eyes of Daniel Defoe, a committed novelist of his time.

From a very young age, Daniel Defoe’s life was linked to the main political events which dragged him away from his respectable origins as a Puritan businessman and led him to support Prince William of Orange. During the Spanish resistance, Defoe was a government agent and very skilfully carried out his mission of monitoring the Scots’ response to the proposal set out by the Union of England and Scotland. At the end of the war, disenchanted with politics and his commercial activities having failed, Defoe took to writing novels over his later years. Until then he had published numerous articles and pamphlets on different topics, such as the Spanish dynastic crisis, which were intended to inform as well as influence public opinion in Britain, although they ultimately reveal the connection between Defoe’s “bibliography” and his “biography”.

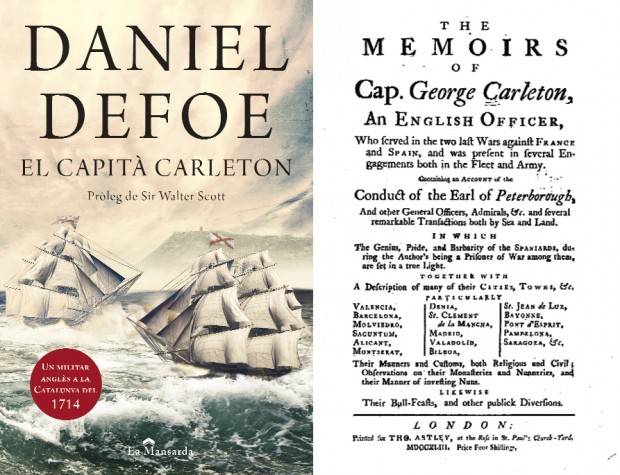

The “case of the Catalans”, which conditioned the peace negotiations between Britain and Spain at Utrecht during the end phase of the war, focused the attention of international public opinion on the Principality. This context provides the backdrop for an interesting novel entitled The Memoirs of an English Officer, printed in London in 1728 by E. Symon. When the Memoirs came out, ten years had elapsed since Defoe had published his first novel, Robinson Crusoe (1719), written when he was almost sixty, and by which time he was an experienced writer. However, Defoe’s book only became known when Walter Scott decided to republish it at the beginning of the following century, in 1809, to put Duke of Wellington’s campaigns in Spain into context during the War of Independence against Napoleon’s troops. Published for the first time in Spanish in 2002 under the title Memorias de Guerra del Capitán George Carleton (University of Alicante) and in Catalan this year, 2013, with the briefer heading El Capità Carleton (La Mansarda), they were well received by historians and the general public and are back in the news.

Historical objectivity and literary fiction

Peculiarly original, the book combines historical objectivity with the literary fiction of the main character. For some time the Memoirs were attributed to their narrator and hero, Captain George Carleton, a real-life character who was included in the Dictionary of National Biography. Not even Walter Scott, in his edition from the beginning of the nineteenth century, had any doubts as to the authorship of the English captain. This is not surprising if we consider Defoe’s effort to present the text as a true story, pitching the narrative fiction to the then-prevailing penchant for memoirs. The realism of the Memoirs made them an invaluable source for most of the nineteenth-century British historians who were interested in the War of the Spanish Succession. Defoe’s novel was based on the handwritten notes of Sir Harold Williams and material culled from other works such as that of Madame d’Aulnoy, as well as on his own memories from a trip to Spain in his youth.

By way of chronicle, the work constitutes a suggestive and unique account of Britain’s participation in the succession conflict. But the Memoirs are not only outstanding for their historical themes; they are also of great literary worth, constituting an interesting document on the character and customs of Spaniards in the early eighteenth century, although they frequently lapse into certain clichés which are common in literary sources. In this regard, the book is faithful to the English tradition of the travelogue, a genre that allows the writer to express his or her point of view with a certain degree of freedom, but not devoid of relativism, on different political and religious issues.

The Memoirs span the period from the Dutch War of 1672 to the Peace of Utrecht of 1713. The fictionalised narrative, focusing on the peninsula, includes a first part dealing with military events which narrates the different aspects of the War of the Spanish Succession: the siege and conquest of Barcelona, the allied strategy, how the Council of War operated and military campaigns, although it also features interesting descriptions and observations on the landscape. Captain Carleton was taken prisoner just after the Battle of Almansa. At this point, the Memoirs become the tale of a traveller observing the reality and customs, traditions and beliefs of the Castilians. While he does give tidings of the main battles, he hopes that “my Interspersing such will be no disadvantage to my now more pacifick MEMOIRS”. He was relocated inland, to San Clemente de la Mancha, the “seat and birth place” of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, where he spent more than three years. In this stage he was surprised at the importance of religion and of the inhabitants’ fear of the Inquisition, but admits that his viewpoint is the opinion of a “heretic”.

The Principality of Catalonia and the Kingdom of Valencia are the main stages of Captain Carleton’s adventures. He has a predilection for Valencia. However, of all the places mentioned, it is the monastery of Montserrat that fills most pages, imbued with a certain mysticism. Carleton is fascinated by the beauty of the landscape and the monastery’s architecture: “As the upper Part was a plain Miracle of Nature, the lower was a complete Treasury of miraculous Art.” Defoe not only describes, in a wealth of detail, the hermitages, scarlet-coloured forests, crystal-clear waterfalls or pure air, waxing lyrical in his delight and admiration, but also narrates the customs of the hermits, such as their food, and the friendly monks.

The cover of the recent Catalan version of the Memoirs, and a London version from 1743 held in the collection of the University of Michigan, digitised by Google.

The keys to the Allied defeat

But the Memoirs also draw a balanced account, tinged with self-criticism, of England’s intervention in the War of the Spanish Succession. The keys to the allied failure and defeat, as well as the English view of the civil war, unfold in their pages. The novelist gives us his own vision of the conflict, never losing sight of British interests, which he analyses with the hindsight of a work written some years afterwards. Perhaps that is why he refrains from siding clearly with any one candidate, and only when England’s economic benefits obtained in Spain are jeopardised at Utrecht does he criticise King Philip V.

The Memoirs dwell at length on the war in Catalonia. The English novelist provides a detailed account of the grim assault on the fortress of Montjuïc, whose success he attributes to the Earl of Peterborough. In fact, the Memoirs constitute a defence of the Earl and were approved by him. One particularly interesting passage is the account of the archduke’s entry into the Catalan capital in 1705 when he was proclaimed king under the title of Charles III, following the commitment taken on in Vienna “to preserve the rights and privileges of the Spanish dominions”; significantly, Defoe interprets the flock of different-coloured birds released at the ceremony as a representation of “the new-found freedom”.

With the exception of the siege of Barcelona, the English captain was not present at any of the major battles that took place in the peninsula during the war. Carleton was in Alicante when he received the news of the Battle of Almansa (1707). Defoe defines the loss in the following terms: “It was a total and utter defeat, the heaviest ever suffered by the British army during the war against Spain.” The Bourbon army did not take long to conquer Valencia and Aragon, marching on to Catalonia. The story describes the consequences of the Bourbon victory in the region of Alicante much more lucidly. By way of self-criticism, he acknowledges that one of the main causes of the allied failure was strategic division, and particularly the rivalry between Galway and Peterborough.

Carleton was in prison in La Mancha when he received news of the allied victories of 1710 at Almenar and Zaragoza, which reopened the road to Madrid for King Charles III. Defoe admits that “the falsest Step in that whole War was this Advancement of King Charles to Madrid”, even if it was the British government that had taken that decision. Following the defeats of Brihuega and Villaviciosa in late 1710, he writes, “tidings of peace arrived”, referring to the Anglo-French negotiations that were embodied in the Preliminaries of London of 1711 and which constituted the foundations of the Peace of Utrecht-Rastatt (1713 – 1714). The Tory triumph in English elections in 1710, representing a public opinion that wanted peace, led Britain to withdraw gradually from the war.

Division of English society

In the course of the negotiations, the commitment taken on by England in the Treaty of Genoa to the Catalans sparked a heated debate in Parliament, which spilled over to the general public. As Secretary of State Bolingbroke put it, “Queen Anne’s honour had to be preserved with the Catalans”. Defoe, in the Memoirs, also mirrors the atmosphere of division in English society that led to the new Tory policy, when he states: “On my Return, I found them… perfect Contraries… Some arraigning, some extolling of a Peace.”

The embassies of the Catalan ministers in the parliaments of Vienna, The Hague and London bent under the pressure of King Philip V’s representatives. Publicists and intellectuals contributed with their writings to publicly support the British parliamentary debate. Defoe took part in the debate defending the government’s pacifist position, whose arguments were picked up in different writings, such as The Balance of Europe and Succession of Spain Considered (1711). Another famous pamphlet, The Conduct of the Allies (1712), by Jonathan Swift, was largely responsible for persuading British public opinion to accept the secretary of state’s policy. In this debate, the Tory government eventually sacrificed the interests of the Catalans. Defoe, with hindsight, seeks to close that chapter in the Memoirs – “Time has shown both were wrong, and consequently neither could be right” – and calls for a reconciliation between the parties. English and Catalan historiography has never forgotten how the Catalan cause was abandoned through the subtle formula hit upon by Bolingbroke.

The Memoirs were published shortly after the signing of the Peace of Vienna between King Philip V and King Charles VI in 1725. The novel is thought-provoking. Perhaps the time had come for the discourse on British involvement in the war to change. Despite everything, Daniel Defoe does not forget to justify what the English did in “an exercise to reassure the British conscience”. It is possible that its initial scant dissemination – it was only printed once in the eighteenth century – was prompted by an international scenario that was not conducive to digging up the past. The Catalans would remind the English monarch of his moral commitment to support them in the recovery of their rights before the government of Felipe V. With the commemoration of September 11, 1714 on the horizon, Defoe’s work is a valuable contribution that shows how the abandonment of Catalonia lingered in the European memory.

Molt interessant! Com portuguès, m’agradaria saber més sobre la intervenció dels soldats portuguesos en la Guerra de Successió, al costat dels catalans. Hi ha alguns treballs sobre aquest tema?

Me chiflaria conocer mas sobre el tema