The archaeological site at El Born is not one of “stones”, but rather of people, of all kinds of activities, working relationships, aspirations, emotions and desires. It presents the complexity of a city and an explanation of a city. The project at El Born Cultural Centre endeavours to make a memory space, a place for historical research and dissemination, and one of contemporary creation.

The long gestation period of the El Born Project has been a very fruitful one. As head of this project until the summer of 2012, I drew attention to the three key elements that underpin the El Born Cultural Centre. This space should be: a place of memory; a space for research and historical knowledge and a hub for contemporary reflection, creation and dissemination.

Regarding the first element, it seems obvious that the archaeological site at El Born commands the utmost value in terms of memory for Barcelona and Catalonia, as any similar place elsewhere in the world would. It contains the last remaining 5% of the thousands of houses demolished to erect the Citadel, the construction of which was one of the disastrous effects of the Catalan defeat in 1714. Despite this uniqueness, attempts to eliminate or undervalue the site have been incessant in recent years, some of them coming almost from within the bosom of the actual project. In this stage, the El Born Project became an observatory of society and witnessed some rather unpleasant events. That being said, other far more pressing and interesting issues than recalling the recent past must be addressed. The whole site has been definitively saved, and that is what counts and is what will remain.

The facility’s contemporary dimension must be fully developed. The idea is to promote El Born as a stimulus to “reflect, create and disseminate information in contemporary times, while in the presence of the past”. Academics and creators from fields such as film, music, the theatre, dance, literature and leisure have worked towards this goal during the project’s preparatory stages and will, of course, continue to do so.

In this brief text, however, I would particularly like to discuss the second item raised above, namely historical knowledge, while taking stock of years of work.

In 2002, a long and widely publicised controversy was expounded in the main newspapers with an intensity that few other issues have managed to stir up in Spain. Nuances aside, the controversy set those in favour of conserving the El Born archaeological site against those wanted to have it demolished to build the Barcelona Provincial Library inside the old market.

A controversy with a backdrop

Some reduced the discussion to the following slogan: “Stones against books”. In actual fact, the stances were closely related to the fact that El Born is not a neutral site, like modern-day Pompeii, but rather is brimming with contents that sparked the squabbling.

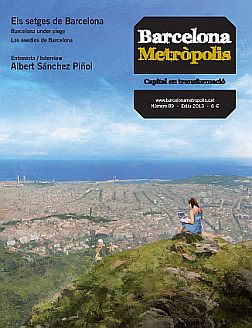

© Dani Codina

The feature that characterises the site and makes it absolutely one-of-akind is the fact that we have documentary evidence of the people who lived in each house of the urban area. In the image, work to prepare the area last spring.

In the course of the protracted controversy of 2002 as to whether or not the site should be conserved, I argued that apart from providing a fantastic memory space, safeguarding the El Born archaeological site also heralded a unique opportunity for the benefit of historical knowledge. El Born is the best possible location to explain a period of history in Barcelona and Catalonia, namely from 1550 to 1714, which for a long time was regarded as one of “decadence”. It proves that this historical era witnessed the advent of modernity to Catalonia. At the end of the sixteenth century, the Principality had consolidated a decisive transformation in its economy and territory, and as of that moment it has progressed steadily on its own two feet: a unique system of cities taking their first steps in production processes, each town or city specialising in different areas (glass, textile, leather, iron, steel, etc.); and a capital where many of the products manufactured in Catalonia were finished, delivering management and service functions to the country as it was efficiently connected to the rest of the world. This far-reaching transformation paved the way for a positive future. In this line, the El Born archaeological site shows how Barcelona’s period of prosperity was not on the same par as the capabilities of big cities such as Paris, London or Naples, but that it was able to compete in the second echelon of Europe’s urban hierarchy. The world of trade played a considerable role in the governance of the city, which was diverse, economically dynamic and very well connected to Europe and beyond by virtue of a sturdy business fabric. It was a city well nourished by foreigners and passers-through, marked by religious observance but nevertheless given to festivities, dancing, music, theatre and recreation. There were also brushstrokes of sophistication: dresses in which colour and adornments prevailed, and truly extraordinary gardens suited to leisure and recreation.

If the city had the strength to resist the grim siege of 1713 – 1714, and also the ability to recover from it quickly, then it was thanks to the foundations laid in the country as of the end of the sixteenth century. Of course, in order to press forward, that society had no need for a would-be rationalisation from outside to open its eyes and point it towards a better future.

El Born explains all this, and it does so in a way that is understandable, enthralling and unique. Indeed, the feature that characterises the site and makes it absolutely one-of-a-kind is the fact that we have documentary evidence of the people who lived in each house of the urban area, spanning a long period at least between the mid-sixteenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth. This knowledge comprises hundreds of thousands of documents explaining what each house and all their floors were like, the contents of each room; what the workshops did and what was sold in the stores; the members of each family, their dealings or relationships with their neighbours and with the rest of the city; the provisions of marriage contracts; who the inhabitants bequeathed their property to; their activities, their business, the countries they traded with; what products they imported and exported, etc.

People, activities and feelings

With all this information, it is easy to explain the overall picture of the city at that time, which we also know in detail, and its dealings with the world. The contemporary and prominent economist and historian, Narcissus Feliu de la Peña, wrote: “A city is not made up of stones, but of its inhabitants.” This maxim is true of El Born. The site is not one of “stones”, but rather of people, of all kinds of activities, working relationships, aspirations, emotions and desires. When all is said and done, the El Born archaeological site conveys the complexity of a city and can explain a city.

Eleven years after the failed controversy of 2002, embodied in the aforementioned slogan, “stones against books”, more than a dozen research works, soon to be followed by more, were published thanks to the El Born Project. Sixty historians laboured over them and oversaw their publication, an effort which garnered the acknowledgement of two Ciutat de Barcelona awards, the Octavi Pellissa award and the National Culture Award. The archaeological site is therefore ready to use its stones, that is, its accumulated knowledge, intelligently. This knowledge, however, must continue to grow in order to keep this cultural space alive. The continuity of the research is indeed one of the essential conditions for El Born to enjoy a promising future.

Felicitats Albert, un gran article i una gran feina que amb el Born Centre Cultural arriben a bon port però que cal continuar: gestió de l’equipament, recerca i publicacions.

M’agradat molt que hagis recordat allò de “les pedres contra els llibres” tenim la memòria molt dèbil i molta gent que ha viscut i crescut a Barcelona els darrers 50 anys no recorda que El Born tal com el podem veure avui va poder desapareixer com a mínim en dues ocasions i el seu salvament es deu a moltes persones que van lluitar per la seva preservació, entre altres les associacions professionals del patrimoni que varem transformar aquesta frase en: volem les pedres i els llibres: ja que uns i altres són fonamentals per coneixer i estudiar la història i les persones que ho van fer possible. Gràcies Albert.