The Catalans committed steadfastly to a legal and institutional framework that catered to the interests of influential social groups but also to those of the “common man”, thanks to the mechanisms of representation and participation developed by their society. The Constitutions were the cornerstone of the whole system.

Barcelona’s heroic 13-month resistance has not always been properly understood by historians and politicians. Some have explained it romantically, others as an irrational act devoid of political meaning. This is to say nothing of those who have denigrated the laws and institutions of Catalonia on account of their supposedly feudalistic character, which were replaced, fortunately in their opinion, by absolutist modernity. Beyond these clichés, one must seek the logic of the desperate and heroic resistance so admired by Voltaire.

To begin with, in order to understand the commitment made in 1705 to the maritime powers, and to Archduke Charles III as opposed to Philip of Bourbon in the War of Spanish Succession, the foundations of the dynamics of Catalan society in 1700 must be explored – the self-same foundations that explain the consolidation of nationhood, as demonstrated by Pierre Vilar.

The economy was pushing towards specialisation, integration and domestic and foreign trade (with England and the Netherlands). Meanwhile, economic growth brought with it the social rise of a bourgeoisie that could achieve the level of honoured citizen, the lowest degree of nobility, thus merging the old and new oligarchy. In this way, the emerging social groups came to play a decisive role in the country’s institutions (particularly in the Conference of the Commons, which brought together representatives of the military, the Council of One Hundred and the Regional Council), which were invigorated by their presence. The notions of participatory government, of a civic discourse and collective memory were deeply rooted in Catalonia, forming a broad-based constitutionalism. However, this tendency to extend participation in public affairs went against the prevailing tide in Europe, whose princes strove to build states that would serve dynastic interests.

Monarchical republicanism

The other core element that defined that society was its legal and political structure – “a Principality without a prince”, in the words of John H. Elliott – the keystone of which were the Constitutions. Although the system had been eroded by the lack of meetings of Parliament since 1599 and by the advance of royal power after the Catalan Revolt, the resumption of constitutionalism was an undeniable reality in 1700, was clearly reflected in the Parliament of 1701–1702 and particularly of 1705–1706, when legislation was passed on key aspects related to the exercise of power, the economy, justice and civil liberty. The outcomes placed Catalan institutions in a remarkable position in European parliamentarianism. At the same time, the political leadership exercised by Barcelona in the principality as a whole is worthy of mention. It was a role that fell largely to patricians and merchants, but also to artisans.

Therefore, the term “republican monarchy” may be used to define this system, organised around the Constitutions regulating public affairs, to the extent that, as the jurist Francesc Solanes said at the time, “it is not the Prince who should be above the laws, but rather the laws above the Prince.” The defence of these laws, above the interests of the group, generated solidarity across the classes.

It is therefore no surprise that as of the summer of 1713 – when it was becoming increasingly evident that the Habsburgs would not recover the Hispanic throne and that the politic powers of the Crown of Aragon would never be restored– the idea of a republic should emerge repeatedly in Catalonia, the result of a logical evolution of the Republican substrate steeped in constitutionalism and patriotism towards a de facto republic between July 1713 and September 1714, which had to organise Catalan political life and provide for its defence in the absence of a monarch.

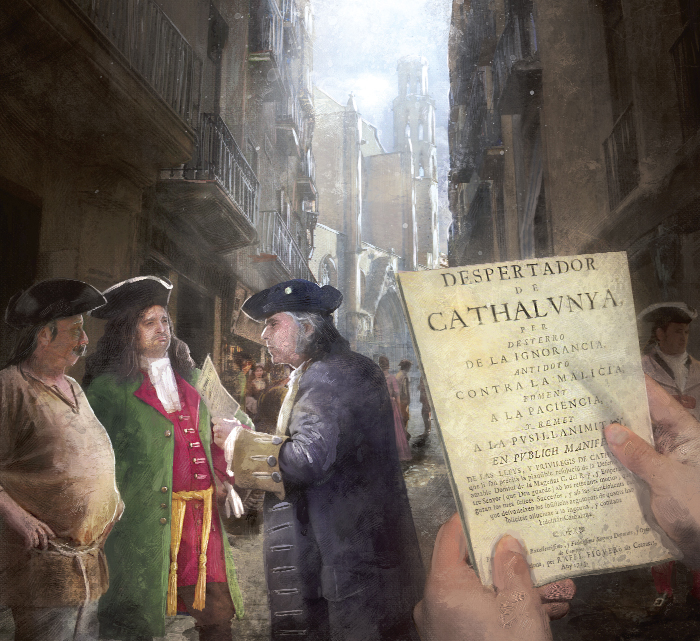

Once the resistance had been approved by the Junta de Braços (the Council of Arms) in July 1713, texts justifying the reasons were published: Despertador de Catalunya (roughly translated as A Wake-Up Call for Catalonia) far from being a compendium of prerogatives of the privileged, appealed to the social benefits provided by the Constitutions in the areas of mobilisation for war and taxation developed by the king. It spoke of defending the homeland, understood not only as a place of birth, but closely linking the concept to its laws, which had to be upheld, as they had been the distinguishing trait of Catalans throughout history. However, it must be mentioned that the unequivocally patriotic contents of the Despertador are not secessionist, but rather are based on the concept of a federalised Spain which had hitherto prevailed, to the extent that it called upon people to fight “for the freedom of Spain” and against the “despotic power” that ruled it. Another political text from 1714, Lealtad Catalana [Catalan Loyalty], was even more blunt, stating that “only the resolutions taken in the Parliament of a kingdom or its provinces are attributed to the Nation […], which is only represented through its united arms. The whole Catalan Nation, together in the Arms, undertook to defend itself from the king that ruled it”, while justifying the Catalans’ right to defend themselves from violence by Philip V.

The “Catalan case”

As is already known, in the negotiations of Utrecht (which yielded the peace treaty of 11 April 1713) the British certified the abandonment of their allies, particularly the Catalans. Nevertheless, the “Catalan case” led to multiple diplomatic negotiations by the ambassadors of the Catalan Commons in Vienna and London to enforce the commitments taken on by Queen Anne of England and Emperor Charles VI. On 28 June 1713, the ambassador Pau Ignasi de Dalmases was received by Queen Anne, whom he asked for support. He begged her to help Catalonia to preserve its liberties and laws, as it had entered the war on encouragement from England, and that “since this country [England] is so free and such a lover of freedom, it should protect another country which, due to its prerogatives, could be called free, which was calling for its shelter and protection, adding that the laws, privileges and freedom are all equal and almost similar to those of England”. While the comparison is somewhat disproportionate, because the Glorious Revolution conquered the highest degree of powers for Parliament at the king’s expense, the concept of freedom and the Parliamentarianism upheld by Dalmases is very significant.

At the last moment, on 18 September 1714, the ambassador Count Felip Ferran de Sacirera was given an audience by the new British King George I in The Hague (he did not know at that time that Barcelona had fallen into the hands of the Bourbons) to whom he delivered a representation underlining the urgency of intervention by the United Kingdom and in which three alternative policies to resolve the “Catalan case” were formulated: “That Catalonia be united with the whole of Spain in the August House of Austria, or that Catalonia, with the Kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia, be granted to His Imperial and Catholic Majesty, or to one of the serene Archduchesses, and if this cannot be arranged, that Catalonia, together with the islands of Majorca and Ibiza, become a Republic under the Protection of Your Highness, the August House of Austria and other allies”. When Count Ferran reported to him on his doings, Dalmases congratulated him, although he also told him that he would have omitted the “serene Archduchesses”, regarding it as an impractical solution (adding, in passing, that the expenses incurred by a monarchy were unbearable). On the other hand, he was highly receptive to the republic option, “since republics love and want or should want and love their fellow men”.

No hope of negotiation with Philip V

Be that as it may, the resistance of Barcelona cannot be explained, in a setting of extreme poverty, social radicalisation and exacerbated religiousness, without considering the hopes the resistance maintained, until the last minute, of an allied intervention, spurred on by the messages of support, often ambiguous, issued by the secretary of the imperial court, the Catalan Ramon de Vilana Perlas, one of the men with greatest influence over the emperor and his adviser between 1705 and 1740. Nor can we ignore another element that is essential to understanding the resistance’s maximalist attitude, namely its conviction that there was absolutely no hope of negotiation with Philip V, as was borne out by the fierce repression undertaken as of 1707. All this, together with the fact that the city’s social forces mainly comprised commoners after most of the well-to-do people had taken flight, and the ensuing radicalisation, conform to the “logic” of resistance, which is difficult to understand if we isolate it from these parameters.

The image of the last moment of resistance, of the counter-attack against the Bourbons, is a striking one, and perfectly mirrors the inter-class cooperation in defence of Catalan freedoms: alongside Rafael Casanova and Antonio Villarroel we see nobles of the ilk of the Count of Plasència, the Marquis of Vilana and Josep Galceran de Pinos i de Rocabertí; the knight Francesc de Castellví; the prominent trader Sebastià Dalmau; the head of the Vigatans militia Jaume Puig de Perafita (who died there), alongside companies of the urban militia of haberdashers and fabric sellers, potters, resellers, tailors, innkeepers and tanners; the lawyer Manuel Flix, a former head minister who was against all resistance; and some regular soldiers such as General Basset, together with many people from Valencia and Aragon, volunteers and the militiamen known as Miquelets.

Once Barcelona had been occupied, one of Philip’s men took stock of the situation: “Boisterous Barcelona, which had been on the lips of many in Europe (and even beyond its borders), thus fell to Spain, after a protracted and courageous resistance […] The fierce pride of this haughty Nation was thus submitted; and in punishment for its crimes, besides the hefty laws imposed, its cherished charters and privileges were taken from it, and it was brought under the government and laws of Castile (which it considers the most oppressive yoke). For even greater security, and to extinguish any remaining hope of longed-for relief, and to subjugate them even further, a Citadel was formed […] The Catalans sadly lost everything they had to lose, namely their freedom, which all the treasures hidden in the earth’s covetous bowels or all the riches in the world cannot equal. They were not made for such harsh martyrdom as servitude.”

Homeland and freedoms

© Dani Codina

Mass demonstration in support of the Statute of Autonomy of 2006, as approved by the people of Catalonia in referendum.

This stark assessment leads us to the reason for the risky and tenacious commitment by the Catalans to that civil and international war – to the political and economic commitment to preserving and strengthening a legal and institutional framework that catered above all to the interests of the rising social groups, but also to those of the “common man”, thanks to the mechanisms of representation and participation developed by that society. This is why the Marquis of Gironella, staunchly pro-Philip, opined that the latter had a “very timely chance to bring all his domains under the same law, to exalt the authority of true nobility, while pruning the excess populace”. To the extent that the Constitutions were the keystone of that system, in the final stages of the war the resistance essentially invoked the homeland and their freedoms, and, to a much lesser extent, Charles III, the king they acclaimed in 1705 and who abandoned them in 1711.

The abolishment of the Constitutions and the introduction of the Bourbonic Nueva Planta decrees constituted a patent political recession. What kind of modernity could there be in the loss of representation, the militarisation of the political structure, the imposition of abusive taxation without the approval of Parliament, and eventually the aristocratisation of municipal powers to the detriment of the local guild representatives and ensuing widespread corruption?