Photo: Pepe Encinas.

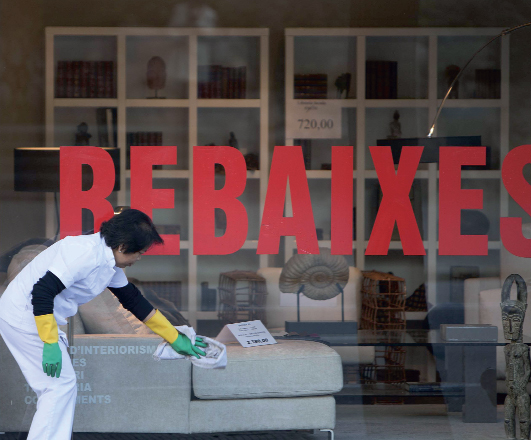

A mother with her child in front of panels advertising women’s fashion in the display window of a large shopping centre on Avinguda Diagonal.

If participation means contributing to the development of a city and not to its planned obsolescence, then the participation of women is still sorely lacking.

Today, Barcelona is predominantly female (about 850,000 women verses 750,000 men), with most women between twenty-five and sixty-five years of age. And for the first time in history, it is a city led by a female mayor, a woman of my generation no less. A symbolic change that will supposedly bring about others, although apparently of a lesser magnitude than in previous times.

In the Barcelona of the 1930s, the time of trams and hats, María Luz Morales was the only woman journalist in the newsroom of La Vanguardia. Then, right in the middle of the Civil War, at the request of the Workers’ Committee, she took the reins and became the first female editor of a national newspaper. Since then, women have progressively gone on to occupy high-profile positions in Barcelona, albeit in fits and starts.

I say in fits and starts because in the not-so-distant year of 1986 not a single woman appeared in the famous photo in Lausanne when Barcelona was named host city of the Olympic Games, an event which changed our image and opened the door to the tourist boom that is now so difficult to manage. Similarly, during the Games, women were very few and far between in many photos of the celebrations and opening ceremony, presided over by the then mayor Pasqual Maragall. It should also be remembered that fewer than 30% of the athletes were women. Like a phoenix, Barcelona rose from the ashes of the period of Spain’s transition to democracy and headed towards the 21st century without women figuring very prominently. And today, does the female majority and the symbolic break with the longstanding androcentric tradition regarding the office of mayor even matter?

During the almost quarter of a century since the iconic year of 1992, we have been exposed to a remarkable dose of what is traditionally known as the “fantasy of equality”. Female Barcelonians, whether natives or adopted (according to the Catalan Institute of Statistics, about 128,500 are of foreign nationality) tread their way through a city where parking is a feat, cyclists are everywhere, but with no kind of control, the tiled pavements of Avinguda Diagonal kill your feet and the city centre smells more and more of fried food. When in the 1970s my uncle from Madrid relocated to Barcelona, it was almost impossible to find a bar in which to have a coffee, while in Madrid they were everywhere. Nowadays in Barcelona there are three or four on every block. And what is more, in tourist areas, girls who are generally soft on the eyes beckon visitors to enter local establishments as if they were peep shows.

A Barcelona full of bars and terraces and filled with both young and mature women. But what do these mothers and daughters who make up the majority of the population actually do? The reality is that they are very under-represented in the local media, and they are also highly under-represented when it comes to the distribution of power. An exception to this latter rule might be the striking case of the Parliament of Catalonia, where 40% of its membership is female, compared to 1979 when women only accounted for 6%.

Given the number of clothing stores per square metre, one might think that about a million women spend their days replenishing their wardrobes or – in view of the large number of businesses dedicated to the art of appearance enhancement – getting in shape, plucking their eyebrows or tanning from head to toe. My mother assures me that when she was young clothing options were few, and that going to the dressmaker was not uncommon when the occasion called for it. But when I myself was twenty years old the offer was infinitely more limited. In particular, the low-cost option – which has democratised fashion and, alas, enslaved the female population to an extent that women themselves are probably not even aware of – was not so common. Today Barcelona looks like a gigantic outlet store. “Barcelona, the world’s best shop,” proclaimed a campaign whose slogan was associated with a prize intended to boost local commerce. Some people believe that a city like that would be every woman’s dream, and they may consider themselves to be right: provided that they have a univocally patriarchal way of thinking.

It never occurs to those who think this way that there might be Barcelonian women who would prefer that more uplifting endeavours were more evenly distributed – such as writing books, directing films or having a voice within the media. It is true that Barcelona is a major publishing city, but women only make up 18% of literary prize recipients. It is also a powerful media hub, but women only participate as columnists and commentators, and in a proportion of only one in four. It is also a moviemaking city, but women direct fewer than one of every ten films that are produced. These figures were prepared by the Cultural Observatory of Gender and provide a highly reliable partial portrait, a good mirror of what kind of society we are.

The deception of consumerism

This mega-store, mega-football and mega-chill out Barcelona where churches are increasingly empty but Messi is God has obeyed to the letter Lampedusa’s rule that “everything needs to change, so everything can stay the same”. The progressive empowerment of women that one would expect of a modern metropolis has been replaced by vulgar consumerism, forcing our women – subjected to the violence of irresponsible advertising – to believe that they are themselves more than ever been before. And that is why, when darkness falls over our neighbourhoods, flocks of butterflies intent on enjoying the “myth of free choice” appear. With their harmonised appearance – miniskirts, long hair and super high heels – they invade the nightspots until the early dawn hours.

Talking of high heels when thinking of prostitution are part and parcel – excuse the synecdoche. I have not found a single official statistic. Not even ABITS, the agency that works to better the situation of women in prostitution and/or who are victims of sexual exploitation, which in some but not all cases is the same thing, seems to have figures. I grew up in the Eixample, and from our balcony I used to sneakily watch the comings and goings of transvestites and transsexuals who sold their bodies in Passatge de Domingo, near the back entrance to the famous old club El Drugstore. From that time, it didn’t take long for the corners of Passeig de Gràcia and La Rambla de Catalunya to become mirror images of Amsterdam’s red-light district. Today, prostitution occupies other more run-down public spaces, as well as other private ones. It is not uncommon to hear the press comment on the huge increase in demand during the Mobile World Congress and other fairs the way one might discuss the price of petrol. Just what we needed: a mega-whorehouse Barcelona emulating the prostitution-rife town of La Jonquera!

It is clear that the “Barcelona of women” has yet to arrive, and that we are still very far from “The Conquered City” that Jordi Borja spoke of. If participation means contributing to the development of a city and not to its planned obsolescence, then the participation of women is still sorely lacking. How is it possible that it has taken a century for a woman to be named director of the Institut del Teatre and that to date only three women have been entrusted to create the posters for the city’s Mercè festival?

There must be something good about the Barcelona of women for it to have avoided succumbing to radical pessimism. And yes, the good news is that globalisation and new migration flows have tinged the city with an enriching multiculturalism that we could have scarcely imagined a few decades ago. Women mainly from Latin American countries work in the service sector, and it is they who tend our shops, walk with our elderly and care for our children. And when domestic workers get together on their days off, one no longer hears talk of Galicia and Zamora, but of Cochabamba. Pity that we are leaving a city with such a sad future to their daughters, who can only look forward to becoming compulsive shoppers or prostitutes, or both at the same time.