Photo: Golda-Pongratz archive.

Palimpsest wall next to the “Forat de la Vergonya” (Hole of Shame) protest site in Ciutat Vella: constructions and deconstructions, with the old graffiti gone.

We are in dire need of a debate on the value of vernacular memory for historical coexistence in the city, something that the law does not always favour. One has to understand the city as a palimpsest, which under its surface hides successive layers of human use.

A palimpsest – a term from ancient Greek – is a manuscript or parchment whose inscriptions have been removed to accommodate new, superimposed ones. With each layer the document acquires a higher density of recoverable traces and thus meanings. Thinking of public space as a palimpsest is a way to better and more deeply understand what we intuitively understand whenever we stroll, walk or rush our way through the streets of Barcelona. This is particularly applicable to the public spaces of Ciutat Vella, where beneath the surface lie multiple layers of human use, inscriptions from different periods, traces of collective and individual uses that are incessantly superimposed, removed, re-inscribed and transformed. The attractiveness of the city feeds off this situation and the way it has been used over time.

The concept helps us understand that these layers overlap each other and that not all of them can always be visible. However, the interpretations made of them are never neutral: the actions of removing, eliminating, highlighting and commemorating are subject to ideological circumstances as well as to the political and urban planning policies of each period. The role of urban space depends on contemporary local and world imaginaries and the overlapping of claims and perceptions, which can change in the space of a few years.

Historically, Barcelona has owed the quality of its public spaces to the care afforded by civil society. The most successful common areas are those whose design unites a desire to preserve history and collective memory with a search for innovative solutions to the needs of the environment, as was the case with many public spaces created in the pre-Olympic period. The Pegaso and El Clot parks are examples of spaces that recycle the memory of the industrial period, provide new uses and then join this memory with the spirit of democratic transition, which is still alive yet overlaps with the speculative urbanism of the early years of the 21st century, which in turn was interrupted by the burst of the housing bubble.

Amnesic spaces and spaces of remembering

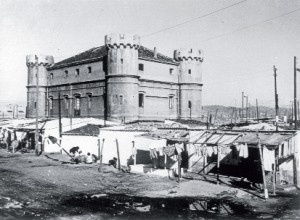

These years have also been marked by the supplanting of urban concepts and civic efforts in favour of a new type of urban planning which eliminates former traces (see the video La ciutat suplantada [The supplanted city], from Repensar Barcelona, presented at the 2009 Venice Biennale), a supplanting that was made most evident at the 2004 Universal Forum of Cultures. That was when the artist Francesc Abad presented the documentation about Camp de la Bota, the site of executions during the Franco regime, whose existence has been covered up by the asphalt platform between the event’s buildings. The mobilisation of the families of the victims and the creation of a civic platform have helped to restore public awareness of the site.1 One can only wish that, as a result of the heartening commemorative policies of the current municipal government, a symbolic awareness of the site can be achieved.

Photo: Poblenou Historic Archive.

The Camp de la Bota in 1960, with the barracas and the castle, a military facility turned into a prison at the end of the Civil War.

Photo: Pere Virgili.

The Camp de la Bota, where about 1,700 people from different groups opposed to Franco were executed, has been buried under the Forum’s buildings and surfaced areas.

The recent transformation of the Turó de la Rovira hill (joint winner of the 2012 European Prize for Urban Public Space) could serve as an example: it is a palimpsest of open layers corresponding to all phases of its occupation, especially during the Civil War and the subsequent barraquismo (shantytown) period. An abandoned space has thus been transformed into a tourist magnet. Monumentalisation, however, carries the danger of a new form of supplanting memory, when it leads to other urbanistic interventions and possible eviction of the area’s residents.

Ciutat Vella’s answered spaces

Pressures from tourists, businesses and political forces on the city’s historic centre culminated to some degree in 2014. The entry into force of the Urban Leasing Act allows the owners of previous rent-controlled properties to raise rents in accordance with market values. Such logic will lead to the replacement of many small businesses, some emblematic, by multinational franchises. The city receives 7.5 million tourists per year, and the opening of new hotels combined with expansive gentrification poses a threat to Ciutat Vella residents of modest means.

In parallel, the tercentenary of the loss of Catalonia’s freedom has been claimed as a symbolic year for those in favour of independence. While the old Mercat del Born is inaugurated as a centre of culture and memory whose archaeological remains were part of the Rec Comtal water irrigation channel, a key part of the city’s development in the 10th century, a few metres away an opportunity to revitalise the former channel was lost when authorisation was given for a hotel to be built on its remains without any attempt to incorporate the ancient structure into the new building’s design. In Barceloneta a move is under foot to recreate old memories in temporary installations, while at the same time the district is suffering from extreme gentrification which has culminated in the privatisation of the old port as well as plans to build a luxury marina in Port Vell.

All of this indicates that we are in dire need of a debate on the value of vernacular memory for historical coexistence in the city, something that the law does not always favour. Discovering palimpsests and evaluating the significance of their layers could contribute to such a debate, as it could also contribute to popular research initiatives and to a model of real inclusion.

Local residents’ resistance to gentrification

Photo: Dani Codina.

The Pou de la Figuera, or Forat de la Vergonya, a unique area between the districts of Santa Caterina and Sant Pere, has been the site of major neighbourhood opposition movements.

There is a unique area between the Sant Pere and Santa Caterina districts which celebrated its 10thanniversary in 2014 and which is the focal point of several urban struggles, converts losses into profits and is an exemplary place of inclusion. Its official name, Pou de la Figuera (fig tree well), refers to the fig trees that grew in that location of the suburbium of the Roman city and next to the fountain of the 13th century textile district. The Forat de la Vergonya (Hole of Shame) is its other name, highly significant for residents and representative of their historical struggle as a counter-model against commodification and social hygiene in Ciutat Vella.

The design of this large area covered with sand and surrounded by trees – which also includes a football pitch, a children’s playpark and an urban allotment – is the result of a long and successful local movement in opposition to the building of a car park and tourist facilities. This opposition left the place looking like a hole (forat) for more than two years. That was when the neighbours began to plant trees, build a fountain and organise film screenings and outdoor activities to oppose the speculation and degradation designed to rid the district of its low-income population. At these meetings, the rich cultural diversity of residents was emphasised, as was the need for a public space due to the high population density and particularly to serve the elderly and immigrant population.

Today a small self-managed neighbourhood centre offers activities for all residents. Located opposite the renovated Palau Alós, now a youth centre, which in 2006 became notorious as the scene of Case 4F (covered in the documentary Ciutat morta [Dead city], which ended with a person committing suicide, an event which needs to be commemorated in some way) and thus the epicentre of the district’s induced decadence at that time.

Opposite the Forat, under the arches of a mediaeval building, a project of integration and multiculturalism has been undertaken that could not be located in a better place: El Mescladís, which, under the motto “Cooking opportunities”, provides needy residents with stable employment opportunities in the restaurant sector. The traditional concept of a neighbourhood is thus expanded, coexistence is strengthened and the local area is enriched with new layers, inscriptions and memories.

Note

1. Comprehensive documentation for the project is available at www.francescabad.com/campdelabota/. A recent publication vindicated it within the context of other sites of remembering: Kathrin Golda-Pongratz / Klaus Teschner (eds.) (2016): “Spaces of Memory – Lugares de Memoria”. Trialog No. 118/119, Berlin, p. 69-73.