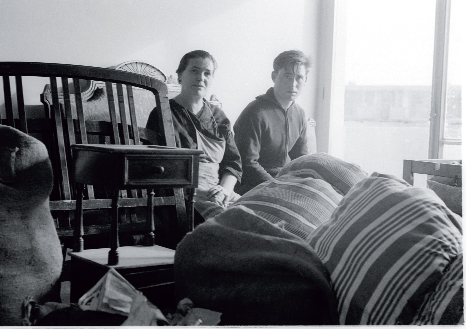

Photo: Oriol Maspons / College of Architects of Catalonia.

Picture from a commissioned photographic essay on the Montbau district’s early period in the early 1960s, which sought to tell a story from a perspective of unbiased realism. The district was designed by the Municipal Housing Board to alleviate homelessness resulting from the large influx of immigrants at that time.

The waves of immigrants from the middle of the 20th century made poor outlying neighbourhoods a disturbing reality at a time when immigration was seen as a problem to be solved through public assistance. To what extent does the stigmatisation associated with peripheral neighbourhoods persist?

A few days ago I was looking through and admiring some photographs in an archive. They were pictures of the Montbau district in the early 1960s. Modern architecture, a model district, urbanistically speaking. Modernity that photographers who were themselves modern liked to emphasise. Needless to say, all the pictures that I looked at on that day were taken by well-known photographers hired by the architects who designed the district, the builders who built it or in some cases the government agency that developed it. In this case, the Municipal Housing Board.

The photographs capture the façades of new and exemplary blocks of flats built during the first phase of the district’s construction. There were also the public squares, wonderful squares that are still vital neighbourhood centres, the places that almost all local streets lead into.

But what where the homes like? I wanted to see their interiors, especially the kitchens – areas that iconographers, except for advertisers, have all but forgotten. I spent many, many hours looking through and admiring photographs. But what about the people? They were nowhere to be seen. Finally a sequence, a kind of essay, showed a man moving a mattress. The pictures tracked him until he unloaded it inside a building. The room could not be clearly seen, but in the middle of the picture were a man and a woman amidst a jumble of furniture, mattresses and various strewn about utensils. I was fixated. Finally I had found someone who would be one of the district’s future tenants.

Photo: Oriol Maspons / College of Architects of Catalonia.

Picture from a commissioned photographic essay on the Montbau district’s early period in the early 1960s, which sought to tell a story from a perspective of unbiased realism. The district was designed by the Municipal Housing Board to alleviate homelessness resulting from the large influx of immigrants at that time.

I heard a voice that said to me: “These photographs are a farce.” What? “They’re a farce,” repeated the voice with the same strength and softness. It was the voice of Fernando Marzà, head of the Historical Archive of the College of Architects. I stopped looking at photos. I was more interested in what Fernando had to say: “The neighbourhood’s residents don’t recognise themselves in these pictures.” The guy telling me this lives in Montbau.

That comment stuck in my head for a few days. I rifled through some papers and found some texts that went with the photos. “These caves, these huts, these impure hotchpotches, origin of the most catastrophic destruction of the family spirit, morbid destroyer of the essence of the species,” the authorities said at the time. The Municipal Housing Board, for its part, drove home the message in these terms: “To house innumerable families living today in deplorable conditions that bring about an amorality that we dare not even describe.” It would not be possible to paint a more disturbing portrait of the future inhabitants of those modern districts. And in the case of Montbau, the Board took pains to make it a socially mixed district and keep it from becoming “red”.

An amoral subject

Despite the architectural modernity, the discursive articulation of the photography, texts and official reports, the inhabitants of peripheral neighbourhoods were depicted as living on top of each other and the overcrowding was said to produce amorality. These people were thus amoral.

Through the tension, in the struggle to define the Barcelona of the 1950s and 1960s, such pictures were intended to offer the appearance of realism, of unbiased discourse. It was the same semblance of realism awarded to Donde la ciudad cambia de nombre (Where the city changes its name; 1957), by Paco Candel, set in the Cases Barates (Cheap Houses) district of Can Tunis, another of the housing estates built during the Primo de Rivera dictatorship in 1929.

Candel’s work was not lost on the residents of the district and their reaction did not leave the author unscathed: “To the angry Cases Barates. One day they wanted to lynch me,”1 he later wrote in the novel Han matado a un hombre, han roto un paisaje (They have killed a man and ruined a landscape) published in 1959.

Who is Barcelona?

Are the inhabitants of peripheral neighbourhoods Barcelonians?

Those in the housing estates are all migrants, regardless of whether or not they really are. In Barcelona, most of us are migrants; first, second or third generation. Since Barcelona demolished its city walls – many, many years ago – it has grown thanks to the contributions of newcomers and others born in the city who ended up moving from one district to another: from Sants to Montbau, from Sant Andreu to La Guineueta, from El Raval to Can Tunis, etc.

” The vast majority of Barcelona’s population are first, second or third generation migrants. “

The pictures of migrants not from the city that have been most widely distributed, apart from the pictures of the migrants themselves, show them carrying highly inelegant suitcases, ready to burst open. We often forget that migration, particularly in the 1940s and 1950s, was fuelled by both economics and politics. People leaving their place of origin for fear of retaliation, due to their Republican allegiance, or those who could not find work because of their political leanings. And people who, in some cases, arrived with professional training and experience that industry (especially the textile industry) made profitable use of. An image that persisted about migrants was that they were always men; they were the first to arrive. Several studies have pointed out that this was not always true. I would particularly mention the brilliant study by Clara-Carmen Parramon entitled Similituds i diferències. La immigració dels anys 60 a l’Hospitalet (Similarities and differences. 1960s’ immigration in Hospitalet). This work sheds light on migratory behaviour by community of origin and shows that in many cases women were the first to migrate.

Immigration was a problem. “An overall negative phenomenon […] the economic and social status of the vast majority of newcomers is much lower than that of local residents”, wrote Jordi Pujol in 1965 in a special edition of the architectural magazine Cuadernos de arquitectura that focused on districts. Migrants were “a concern” that had to be addressed through “assistance”, in the words of the author, and not through the recognition of their rights.

The reluctance to consider them as Barcelonians did not just apply to the first generation; it also applied to their children, who were branded with the pejorative term xarnego even when they had a Catalan parent.

But not in all cases. It would have been problematic to use such a term to describe someone with the compound surname Muñoz Ramonet as in the case of Julio Muñoz Ramonet. The son of an Andalusian father and a Catalan mother and one of the most important textile barons of the Francoist period, he died in Switzerland to avoid being jailed for tax fraud. Being considered as either a migrant or a xarnego had to do with one’s economic level, not with one’s geographical origins.

Disturbing housing estates

Peripheral neighbourhoods have always been a source of disturbing news for both specialised and general publications. They could have been and may today be considered an architectural or urban planning problem; they could have been or may be a problem of assimilation, behaviour, drugs – yes, yes, of selling drugs, of sex, of rock and roll – but a problem to be sure.

The peripheral housing estate was “a disease, a public disease of immense proportions,” as written in the magazine Tele/Estel on 18 November 1966. Geographical accuracy was not of importance when discussing behaviour considered inappropriate for a citizen of Barcelona. The term suburbi (slum/housing estate) did not always refer to a specific area. It was a construct, a discursive utterance.

What bargaining power did these people have with images that depicted them in a particular way?

Photo: Ginés Cuesta / Historical Archive of Roquetes-Nou Barris.

Madame Gertrudis in her tidy kitchen in the Cases del Governador housing estate, as photographed by her neighbour Ginés Cuesta.

Photo: Kim Manresa / Historical Archive of Roquetes-Nou Barris.

Local residents as political actors in a picture by Kim Manresa from the late 1970s.

Actor and photographer Ginés Cuesta, a resident of the slum of Les Corts, who later moved to the Les Cases del Governador housing estate in the Verdun district, took pictures of a neighbour of his, Madame Gertrudis, in the kitchen/dining room of her home. It was a kitchen/dining room that, despite its small size, was not at all cluttered or crowded. Ginés Cuesta portrayed Madame Gertrudis without dishonesty. There they shared “a community of meaning”, in the words of Martha Rosler. Kim Manresa, another photographer and resident of the city outskirts, produced pictures of his neighbours that showed them as actors in a political setting, if we understand politics to consist of being with and acting amongst others.

From Sant Adrià, Javier Pérez Andújar wrote Paseos con mi madre (Walks with my mother; 2011): “You cannot have a close relationship with Barcelona if your ancestors did not.”

To what extent do the stigmas assigned to the inhabitants of peripheral neighbourhoods persist? What mechanisms perpetuate them? Who or what do these neighbourhoods threaten? And finally, how do these stigmas affect the lives of the residents of the districts?