Photo: Mery Cuesta archive.

Works of art by inmates in the La Modelo, Brians 2 and Quatre Camins prisons, including the installation La mirada nómada (The nomad gaze) created in the Brians 2 prison yard (the two pictures on the left in the second row).

Let’s place ourselves on the absolute fringes of the citizenry – in the prison system. There we will discover an unlikely way in which the prison population rubs shoulders with the rest of society: through artistic creation.

We’ve grown all-too accustomed to hearing the term “citizenry”. This 100th issue of Barcelona Metròpolis is a good occasion on which to reflect on the limits of this concept. Because such limits exist. Considering its various definitions, we find in all of them the basic notion that the citizenry is comprised of individuals who can politically influence the government of their country, people who are in a position to fully exercise their civil rights.

Let’s talk about a group that is not part of that citizenry: the prison population, a segment that is often put into the category of “a group at risk of social exclusion”. This expression, which originated in France in the 1970s and has received the blessing of the European Union, is used to refer to social groups that are wholly or partially excluded from full participation in society as regards political and economic life. They are individuals who are unable to exercise the right to vote and cannot participate in the official labour market: they are not part of the citizenry.

The meaning of “social exclusion” is essentially clear to the whole of society, but many of us feel uncomfortable with this label. It seems to harbour a latent threat, a sword of Damocles that may fall at any moment and cut the umbilical cord linking those individuals or that group who are “at risk of exclusion” with “society”. Such language is negative and exclusionary: it would be more appropriate to use an inclusive and positive expression that might engender empathy for these “risks”. Furthermore, it is impossible for these groups and individuals to stop being part of society. They are integral part of it, and it makes no difference whether instead of living in an apartment in London’s Soho district they inhabit a jail cell. It is paradoxical that the idea of social exclusion is applied precisely to those who are most intensely subjected to the pressures exerted by our social institutions.

Having placed ourselves on the absolute fringes of the citizenry, let’s examine one way the prison population rubs shoulders with the rest of society: through artistic creation. Prisons are like cysts: closed nodules with their own systems of symbols and meanings within the matrix of the social sphere. I have been fortunate over the last three years to have researched the artistic and creative work that takes place within this collective, namely Catalonia’s ten prisons, seven of which are located in the province of Barcelona. Within the Catalan prison system can be found a particular kind of professional that does not exist in the Spanish national system: in-prison artistic tutors. The aim of these intermediaries goes far beyond keeping inmates entertained. They attempt to ensure that inmates derive some cultural and personal benefit from their time behind bars. They achieve this by enriching the inmates’ internal symbology and sensitising them to forms of artistic expression and languages they do not know. The mission of tutors is initiatory: to inspire the dawning of creative intelligence. Today, the Catalan model of prison art education is studied and emulated in prisons elsewhere in Europe.

At present there are 53 tutors for ten prisons. A range of practical activities such as expositions outside prison, competitions and prison visits by renowned artists have helped these cloistered institutions –micro-universes with their own strict and arduous routines – to acquire a certain porosity. It thus becomes possible both to receive encouragement from the outside and make contributions to the social sphere that tell the tale of prison life and highlight the dilemmas that prisoners face. The language of artistic creation, because of its metaphorical and poetic power, is very useful for combining both spheres.

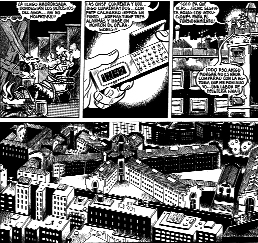

Photo: Editorial La Cúpula.

A page from the Fuga en la Modelo comic book featuring the character Makoki, published by La Cúpula.

La Modelo, a popular cultural myth

I would like to briefly dwell on the case of the La Modelo prison’s face-to-face struggle with the city. Its location in the middle of the Eixample district gives the metaphor of the prison as a social cyst a particularly literal meaning. Huddled in the middle of the streets of Rosselló, Provença, Nicaragua and Entença, this building constructed in 1904 is one of the oldest Catalan prisons and an emblematic one due to its panoptic architectural design. La Modelo (known in Barcelona street lingo as “the hotel”) can be considered as a myth of our own popular culture because it has its own collective image based on a shared imaginary.

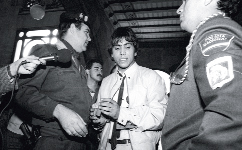

The top three phenomena associated with La Modelo that figure most prominently in the minds of uninformed Barcelonians are probably, firstly: the riots and uprisings led by the Coordinating Committee of the Spanish Prisoners in Struggle (COPEL, by its acronym in Spanish) in the late 1970s. Images of inmates occupying rooftops during that incident have left an indelible mark on the memory of several generations. To these images we would have to add those of the 1984 riot, which was made into a media event by El Vaquilla when he asked for heroin before the cameras. And finally, the zany comic narrative Fuga en la Modelo (Escape at La Modelo) by Gallardo and Mediavilla, one of the most well-known adventures of Makoki, antihero of the Barcelona comic scene.

Photo: Robert Ramos.

Juan José Moreno Cuenca, known as El Vaquilla, leaving a trial in the Court of Barcelona on 30 April 1985.

These three phenomena are closely related to popular culture and the media, and are just the tip of the colourful mass media iceberg surrounding this huge architectural, historical and cultural artefact that is La Modelo. This important place for memory holds within it a wealth of experience marked by pain and punishment, as well as experiences of learning and defiance. Inside this building, I saw how the tutors that we have mentioned here are implementing new and innovative methodologies and techniques through artistic education. I think of the ways that inmates were taught to stimulate the five senses using sensory inputs (smells, tastes, etc.) that would later be expressed as some sort of graphic or sculptural work. In such experiences, smell is the stimulus that has the most vivid effect on people. For someone living in the absence of freedom, the smell of a simple rosemary sprig is enough to unleash a torrent of tears.

Describing all the exciting projects I have learned about that were carried out in La Modelo and in other Catalan prisons would take up too much space. It is imperative, however, to mention the generosity of artists such as Arranz Bravo, Frederic Amat, Evru and Mag Lari. Their selfless visits to the prison have helped to strengthen aspects such as self-improvement, will-power and perseverance amongst inmates. These visits bring the prison into a kind of synergy with the citizenry in which a particular quality is breathed and filtered from the inside of prisons to the outside and vice versa: that quality is creativity. We must therefore demand the introduction of a culture capable of appreciating that which is created in penal institutions. This would, undoubtedly, be a most powerful way of welcoming these people who live on the margins of the citizenry into our society.