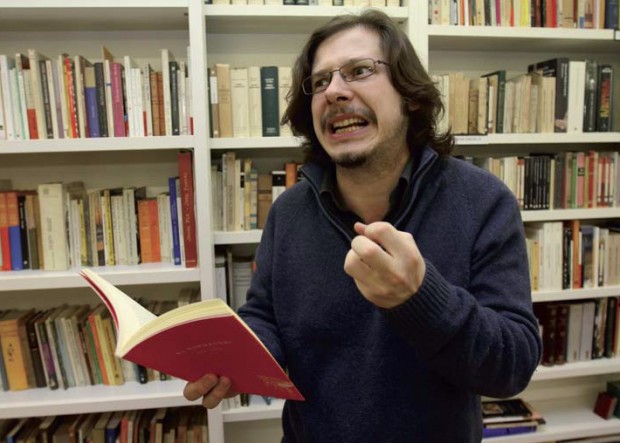

Author: Adrià Pujol Cruells

Publisher: L’Avenç

152 pages

Barcelona, 2018

The book by Pujol Cruells is neither pleasing nor insulting. By means of the passing of the year, he draws an image of the people of Barcelona based on a meticulous observation of their customs, oddities and craziness.

A large part of the texts from the 20th century on the citizens of Barcelona evoke the people of Barcelona of the 19th century, in an exercise of well-meaning nostalgia. A clear illustration of this is Los buenos barceloneses, by Artur Masriera (1924), which introduces us to the serious and circumspect Barcelona of the nineteenth century, with many a top hat and frock coat, at the opposite end to the revolutionary riots. Giving birth to the myth of the “gentleman of Barcelona”. After the Restoration of 1874, Barcelona is a city that wants to forgive itself for the

commotions, barricades and burning of churches and convents, a tradition typical of Barcelona which, if staged today in the form of a son et lumière show, would be a delight for the tourists. This is why the people of Barcelona went to great lengths to erect expiatory temples and to idealise the city without any foundation, since “the history of civilised mankind is nothing but the history of its misery, where all its pages are stained with blood”. We won’t contradict Diderot now.

Els barcelonins by Adrià Pujol Cruells (L’Avenç) is preceded by two nearly identical titles: Los barceloneses by Sempronio (1959), accommodating and slightly insulting, as the time required and its author was happy to oblige, and Els barcelonins by Anna Maria and Terenci Moix (1984), a literary filling within a photographic album by Colita, Oriol Maspons and Xavier Miserachs. Els barcelonins by Pujol Cruells is neither pleasing nor insulting, and definitely not a filling. “Vamos para bingo.”

Through the passing of the year (each month a chapter of the book had been published in the magazine L’Avenç in a section named after the title of the book), Pujol Cruells draws a portray of the people of Barcelona based on a meticulous observation of their customs, oddities and craziness. But Pujol Cruells is no flâneur –he doesn’t fall for this kind of tackiness–, but he earns a living, raises two daughters and stoically resists the attacks of adversity in the Barcelona he depicts.

The book starts with losing a stable job at a dehumanised design school, which coincides with a commissioning, as an anthropologist, of an exhibition on the people of Barcelona at the Ethnological Museum.

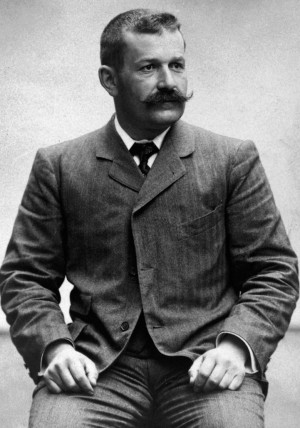

Pujol Cruells aims to “understand how the nature of Barcelona is built”. Or what is left. As an anthropologist and as a citizen. He is a citizen of Barcelona like so many others, born in a town, Begur in his case, with close ties to the Empordà landscape and now well-established in the city after many years of living there and fighting to do so. For better understanding, Pujol Cruells would be a candidate for directing the Athenaeum of Empordà in Barcelona, at number 11, Carrer del Pi, if it were ever to reopen.

In Els barcelonins, Pujol Cruells portrays a number of characteristic urban specimens, such as cultural managers, conceptual artists, intellectuals on contract, time-out hipsters, consultants of the Administration, alternative charlatans, those in the creative hangars and others. They are our “pimps, bullfighters and Manolas”, the modern purity of Barcelona, all framed within a certain degree of imposture. According to the author, the identity of Barcelona is a strategy. One of survival and power.

As a counterpoint to this carnival-like rua, Els barcelonins looks into some of the oldest traditions of Barcelona: Santa Eulàlia, Sant Ponç fair, Sant Cristòfol, the evening of Sant Joan, All Souls’ Day (despite leaving out the crown jewel, the Corpus Christi procession). Always advancing in the company of his very own Know-it-all, the voice of consciousness who reprimands, warns and doesn’t let any kind of imposture go unnoticed. Because, while Barcelona is an all-year-round Carnival, Pujol Cruells doesn’t dress up.