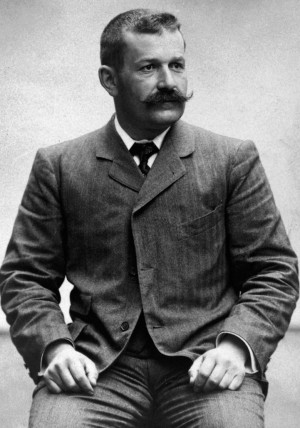

Antoni Piera i Jané was a quiet, tough and resolute man. He never talked about himself or his work, and was not one for waxing lyrical. He was what men used to be like back then, before they were defeated by sentimental and psychological prattling. He was one of the founders of the construction company Foment d’Obres i Construccions, in 1900, and became its manager one year later.

Sants, a town within sight of Barcelona, surrounded by vineyards, gardens, cherry-tree fields, farmhouses scattered here and there and a few roadside hostels. Factories, as well. I would say that it is around 1850 or 1860, and I do so on the strength of the hoop skirts worn by some young fashion-followers strutting along Creu Coberta. A young carter, Antoni Piera i Sagués, is lugging a cart full of cloth. Everyone calls him Ros d’en Maiol (or Mallol) simply because he is blonde.

He is a descendant of the Piera family of Can Bruixa, a farmhouse in Les Corts that was demolished in 1946. The name of this house, Bruixa, which means “witch” in Catalan, stems from a very unique skill: the Piera family used to buy sick horses, heal them and then resell them at a much higher price. How they managed this remains a mystery. Healing sick and lame horses is an art; you have to know the secrets, and it requires a great deal of patience and skill. Not something to be attempted at home.

Antoni Piera i Sagués transports Batlló cloths all over Spain. A whole string of mule-driven carts laden with cloth picks its way along the road to Zaragoza, Burgos and Valladolid. And that is how the Catalans, tough and tenacious folk, earn their living. Times were different then.

The advent of the railway network led the fabrics to be transported by train and the carters lost their jobs. So Antoni Piera i Sagués purchased a quarry in Montjuïc from Batlló. Montjuïc stone, light brown with purple and wine-coloured streaks, was in great demand for building houses in the Eixample, the neighbourhood that was inexorably spreading over the plain of Barcelona. The carts were now used to haul the stone from the quarry to the building site. He bought up one quarry after another and eventually owned all the quarries on Montjuïc. El Sot del Migdia is an old quarry, as are La Foixarda and the Teatre Grec. When the spectators got bored with the performance they turned to the quarry for distraction. It is a phenomenon that greatly enriches contemporary theatre.

During that period, Ros d’en Maiol (or Mallol) married a girl from El Prat de Llobregat, Antònia Jané, and built a house with a garden and stables in Carrer de Sant Pere in Sants, now Carrer de Sagunt, where the Escola Perú is located. They had six children, and the second-oldest son was Antoni Piera i Jané, born circa 1872, if my calculations are correct. He was destined to become one of the founders of Foment d’Obres i Construccions in 1900.

As of 1893, the Piera family had a construction company that was smaller than Foment, called Piera, Cortinas i Cia, which engaged in the exploitation of quarries, building and public works. Why did they found Foment? To set up one of the most important construction companies in Barcelona, with the contribution of capital from Mas Sardà Bank and Soler i Torra Bank. They had the stone, bricks and wood (the Cortinas family were carpenters); all they needed were investors. Eleven shareholders put up five million pesetas, by no means chicken feed. Barcelona’s growth was unstoppable and someone had to do the building.

Fomento’s first job was to build the piers known as Moll d’Espanya, Moll de Balears, Moll Nou and Moll dels Pescadors, all inside the city’s port. Years later they expanded the port, paved the streets, cleaned up the sewers while also planning and executing new ones in Barcelona, Zaragoza and Madrid; they covered the Sarrià train line along Carrer de Balmes and also built the tunnel for the new stretch between Plaça de Molina and Avinguda del Tibidabo in the Sant Gervasi gully. However, Foment really came into its own, if I may say so, in the construction of the palaces, streets, hotels and pavilions of the 1929 World Expo. It built four hotels in Plaça d’Espanya in record time. Once it got going there was no stopping it.

Throughout this whole period, from 1901 to 1933, the Managing Director was Antoni Piera i Jané. This was because in 1901, one year after its foundation, the manager at the time – his older brother Salvador – passed away suddenly. He lived in Can Puig, in Collserola, and had been somewhat under the weather. One day he went out for a walk, took a drink from the Font Groga, and died shortly after, perhaps still clutching his mug. That was how Antoni Piera i Jané became the manager of Foment; my great-grandfather, it must be said – the father of my grandmother, Carmen Piera.

My great-grandfather was known as Antonet or Tonet, and as the years went by he became Senyor Tonet or Senyor Antonet, whichever one people prefer. A friendly, intimate name that evoked his humble origins.

Antoni Piera i Jané was a quiet, tough and resolute man. He never talked about himself, his childhood or his business. Not one for waxing lyrical. That is what men used to be like back then, before they were defeated by sentimental and psychological prattling. True to his reserved nature, and by then married with kids, he rented the farmhouse Can Girona to spend the summers. It was a secluded farmhouse in a small town near Barcelona called Martorelles. It was far removed from the towns where Barcelona’s bourgeoisie spent their summers. All Piera wanted was some peace and quiet; he had enough on his plate with managing Foment and in Can Girona he was his own man. To this day, the road that starts near the crossroads at Sant Fost bears his name: Avinguda d’en Piera. We will also call it that.

When he wanted some amusement he went to the bullfights. Even as a young man, he and his older brother Salvador used to ride the bulls in the local festivities of Sants. When he was older he did not miss a single bull fight in Barcelona. One summer he followed the bullfighter El Gallo all over Spain. This passion was inherited by his two sons, Antoni and Josep, some of his grandchildren, such as the film director Antoni Ribas, and even the odd great-grandchild. Piera was also a practical man, not given to intellectual digressions. During a trip to Paris he hired a guide at the Louvre and told him in French: “Show us the lot in one hour!” There was no messing about. Neither was he short on decisiveness. At one Foment shareholders’ meeting, he became embroiled in a heated discussion with the banker Mas Sardà, and exclaimed: “Either Mas Sardà leaves this room or I’ll throw him out the window!” Years later they were in-laws. All’s well that ends well.

© FCC Archive

Signature of the deed of incorporation of the company Foment d’Obres i Construccions on 3 July 1900. The second figure on the left is Antoni, and the third his brother Salvador, the company’s first managing director.

Politically, he was in favour of the powers that be. Like many Barcelona businessmen, in 1923 he supported the coup by General Primo de Rivera, plotted by the Military Command of Barcelona. Sixty years later, his daughter Carmen still defended him staunchly: “Primo de Rivera brought us peace.” She must have heard that at home.

Due to the gunfighting crisis during Alfonso XIII’s reign, Piera decided (I would venture circa 1919 or 1920) to close the house in Sants and take up residence in Barcelona. He and his family lived in the Hotel Continental for a whole year. They later rented an apartment in Casa Garriga Nogués. In the meantime, he commissioned the architect Josep Maria Ribas i Casas, his future son-in-law, to build a house in Carrer de Mallorca, in 1924.

I suspect that he was hardly enamoured with the advent of the Republic. We know that in 1933 a Foment worker burst into his office and threatened him with a gun. We know not whether the man was a revolutionary or a mere robber. Piera managed to overpower him and everything seemed to be back to normal. But Piera returned home ashen-faced and was unable to sleep that night. He felt unwell the following day. He had ruptured a vein in his heart, which was silently bleeding. When they realised, it was already too late: his lungs were flooded with blood and he died four days later. We know all this through stories handed down, as there is no record of the attack at the office in the press. It was all kept secret.

Piera was laid out at home. The worker who had attacked him turned up unexpectedly, repentant, and apologised with tear-soaked eyes. Before letting him in to pay his respects, the maid asked the widow, who responded with dignity: “I forgive him, but I do not want to see him.” The dejected assailant returned home. All in all, it could be part of a story by the great Josep Maria Folch i Torres.

His grandchildren paid their last respects to him, one after the other, as he lay on his deathbed. A kiss on a cold, stiff hand. And I, from here, pay my own.

No veig quan es va publicar aquest article, però és avui que he conegut una mica l’existència de la saga Piera en el Museu de Carruatges d’Horta, a Barcelona. Fascinant tota la història del transport de cavalleries, traginers, capacitat de veure el negoci, amb tot un món desaparegut. Seria molt adient fer tota la història des del traginer Antoni Piera i Sagués. No ho heu pensat?

Es un una historia molt interesant yo estig molt interesat per la part de la limpieza de Barcelona ya que soc net y fill escobrires que subcontractats per el FOC SA. Ting molt present les cuadres y el tallers a la Gran via al devant de la Estacio de Magoria. Al tallers fabricavan tota mena de maquinaria per la limpeza de Barcelona. Y les cuadres per a mi eran com un mond de maravellos.