Through a twist of fate that I do not seek to comprehend, I was privy to something that some people would not hesitate to call an encounter. Seeing it was no merit of my own since, surrounded as I was by the general euphoria, I just allowed myself be carried along.

It was 1997, on a particularly cold November day, in the publisher’s office, when people began to emerge from their trenches, which consisted of a ramshackle desk and a small heater which we took it in turns to connect to the mains. The reason for all this hullabaloo was the unlikely call that someone had received from the other side of the Atlantic. It was the Little Brown publishing house, according to some, while others vehemently denied it. The fact of the matter was that David Foster Wallace was in town, fleeing from the promotional tour for his mammoth Infinite Jest, and here – although nobody had actually read a single word of the book – we would have challenged anyone who dared question its worth to a duel.

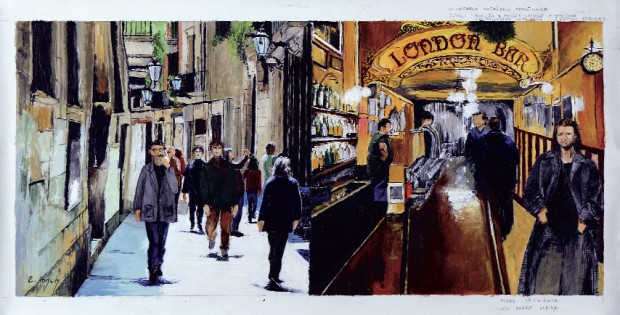

A cold Barcelona blasted us as soon as we jumped out into the street. We were running behind Ignacio Losada, the bearer of the privileged information, who was leading the small throng like an illustrious standard bearer. Eventually we almost battered our way into the historic London Bar, where Wallace had unknowingly joined the distinguished list of clients headed by Gaudí and Picasso. Ignacio had been entrusted with rounding up, capturing and returning Wallace to the airport. The rest of us, lounging in a luxurious box, ordered drinks and sat down to observe the unequal battle.

Recalling the scene now, I think I could say that Wallace’s every move, every word uttered in his deep English, all those bad things were not only disease but also the kaleidoscope whence he hatched his literature: a pathological maze of hilarious, extenuating monologues, a monument erected by an exacerbated, excessive consciousness that turned on itself. However, none of that was known to me then, and I simply marvelled at his massive figure, my gaze seeking to follow his hieratic gestures, because he was already drunk or high, when he suddenly started to scream, enraged, behaving like a false Hamlet who while listening to his uncle’s confession was already feverishly plotting his revenge.

Moments after the limbic seizure had inexplicably possessed him, the colour drained from his face and he turned pale. Wallace stepped out onto Carrer Nou de la Rambla, perhaps to throw up, thus subscribing to the historical spirit of the erstwhile red light district, legendary scene of nights of hell-raising and dens of iniquity. Resigned and apathetic, Ignacio Losada followed suit.

It was then, looking around me, that I noticed the presence of one of the recent discoveries of the Barcelona publishing industry, a Chilean writer who had just published a work that fell within the realms of Marcel Schwob and Borges: Nazi Literature in the Americas, a fictitious anthology of imaginary writers. However, at that time Bolaño was not yet Bolaño, nor Belano, although he had always been so, and ever since then I torture myself thinking about the spectacle I missed and which I can now only imagine.

I imagine a watchful Bolaño, his gaze steady behind his glasses, monitoring Wallace’s gestures as if they were Carlos Wieder’s acrobatics in the sky; or a romantic Bolaño lost in Ciutat Vella, as he was long before he started to publish, living not far from there in a filthy attic on Carrer Tallers, now fascinated at having found another exile in the London Bar, another immigrant, even if it were just for one night; or even a sick Bolaño who saw himself in Wallace’s eyes, except that his suffering was of a different kind.

It is both easy and alluring now to discern Wallace’s excessive but terribly human traits after the ambivalent figure of Klaus Haas in 2666. Or encrypted in the strange main character of Snow, equally verbose and digressive. However the simple truth is that Bolaño just sat there, smoking away, impatiently waiting for a return which was obviously not going to happen. I found no reason to postpone my departure.

I like to think that an upset Bolaño left the bar soon afterwards, wandering aimlessly, guided by the body’s memory, recalling the streets of the Raval which for years had been his shelter; tumultuous years, spanning the decline of the red light district, with the arrival of heroin and immigration in the mid-seventies, and the reform that put an end to the sad spectacle: the demolition of the so-called isla negra and inspections in bars and meublés.

While from my window in the present it inevitably strikes me as ironic that this lumpen space, once ruled by immigrants and thugs, the landscape that Bolaño lived in and immortalised, has been disguised by the scaffolding of haute culture, the museums of post-modernism; that it has been colonised by vintage clothes stores and supermarkets of the subculture. A neighbourhood finally transmuted by a hyper-encoded aesthetic, falsely alternative and self-conscious. Perhaps as if the addictive personality of David Foster Wallace and his literary universe, logoleptic and tragicomic, had left an indelible mark on it.