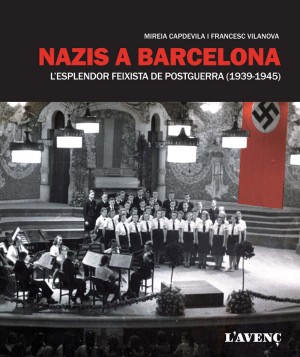

Nazis a Barcelona. L’esplendor feixista de postguerra (1939-1945) [Nazis in Barcelona. The fascist splendour of the post-war period (1939-1945).]

Nazis a Barcelona. L’esplendor feixista de postguerra (1939-1945) [Nazis in Barcelona. The fascist splendour of the post-war period (1939-1945).]

Authors: Mireia Capdevila and Francesc Vilanova

Publisher: L’Avenç and Barcelona City Council

227 pages

Barcelona, 2017

It is no secret that the Franco regime, in spite of maintaining a formal neutrality during World War II, was enthusiastically addicted to the fascist side (Paul Preston outlines the most salient details of this partisanism in his biography of Franco, published in 1994). However, no book had previously managed to describe the extent to which this support for fascism manifested itself visually, both officially and in the popular arena. Nazis a Barcelona fills this void in Catalonia’s collective historical memory.

In a nutshell, the Francoist government and military were quite open about their support for the regimes of Hitler and Mussolini: they invited high-ranking Nazi and fascist officials to Barcelona and other places in Catalonia and treated them to gala dinners, medals and praise-filled speeches in which the fascist and Nazi struggle was described as a seamless continuation of the Francoist Crusade. Nazi Germany’s propaganda magazines and pamphlets – not to mention Hitler’s speeches – were disseminated in Spanish throughout Spain. The Military Officers’ Residence in Barcelona was fitted out with a Germany Hall featuring a bust of Hitler on the table and a framed swastika on the wall. (The swastika, by the way, became a commonly used emblem at the University of Barcelona, the former Catalan Parliament, the Barcelona Provincial Council, Barça stadium and the Palau de la Música).

The book is packed with shocking photographs – many unpublished or little known – of the countless pro-Fascist events that were held in Barcelona, Montserrat, Sabadell and Terrassa. How disturbing it is to see a children’s choir singing at the Palau de la Música in celebration of Hitler’s birthday, or the monks of Montserrat laughing heartedly while shaking hands with Heinrich Himmler.

However, if something is perhaps lacking in the book, it is reference to what the Nazis were doing between their visits to Barcelona, which would explain why these visits were so obscene. For example, when Himmler arrived in 1940, his special SS squads called the Einsatzgruppen had already shot dead hundreds of thousands of Jewish and Polish civilians. In 1940, SS troops established the ghettoes in which thousands of people would die of starvation. In 1941 nearly one million Jews were shot in the territories that the Germans occupied during their invasion of the USSR. 1942 saw the opening of the Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka extermination camps, where 1,274,166 Jews, Roma and Poles were killed – either gassed, shot or beaten to death. Between 1943 and 1944, 1.1 million people – most of whom were Jewish – were gassed in Auschwitz, and another 79,000 – again mostly Jews – were gassed or shot in the Majdanek fields (18,400 in a single day in 1943, on the day of the harvest festival, officially celebrated in Barcelona by the German community and several Francoist officers at the Palau de la Música).

If it is possible that Franco’s government knew nothing about the Shoah at the beginning of the war, it is inconceivable that they had no reliable information about it from late 1942 onwards. They nonetheless continued to support Hitler until 1944. Perhaps it would not be a bad idea for some of today’s politicians – before accusing certain Catalan public figures of being Nazis and fascists – to look back at the attitudes that some of their predecessors had towards the real Nazis and fascists between 1939 and 1945.