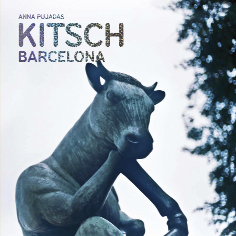

Author: Anna Pujadas

Barcelona City Council

Barcelona, 2016

Everything that tourism touches turns into kitsch. This may be the inevitable conclusion to be drawn from a reading of Kitsch Barcelona.

The book, published by the Barcelona City Council and edited by design theorist Anna Pujadas, sets out to be an exhaustive catalogue of the most emblematic expressions of kitsch which, consciously or unconsciously, also form part of the city’s personality. Pujadas, who offers us an introduction to this phenomenon, asks us to see it not as something to look down upon, but as something to celebrate. In this vein, some thirty different designers, architects, anthropologists and writers have curated and illuminated a collection of our very own home-grown kitsch.

Possibly, the most obvious success story is Gaudí’s mosaic, used everywhere and elevated to sublime levels at a McDonald’s on Passeig de Gràcia. Then we have examples of historic kitsch that are worthy of vindication as they are part of our tradition, and which range from the Poble Espanyol to the Lady with the umbrella sculpture to the church on Tibidabo. Another group, including the statues on La Rambla and Claes Oldenburg’s sculpture of giant matches, is proudly being reborn from the ashes of Olympic Barcelona. We can even consider our recollections of the albino gorilla Snowflake as a kind of kitsch memory game, even though what is really kitsch is the fact that the gorilla was given his very own national identity card. And how about our memories of the banana splits at the 7 Portes restaurant? What is clear today, however, is the fact that some of the visual milestones of our childhoods are now in the hands of an absolutely ruthless tourism industry and have consequently been trivialised by the masses and distanced from our personal experiences of them. Whether you call them kitsch or just plain cringeworthy, some things such as the Lladró ornaments shops or adverts for Crujicoques are so universal that they attain a kind of meta-kitsch status (a bit like the works of Carlos Pazos, born with kitsch intentions).

The second conclusion we can draw from this book is that kitsch is, above all, a subjective way of looking at things. Such subjectivity can be found in the attempt to put some kitsch into Barcelona’s image as a tourism destination for “foodies” (such an irritating word), with glorious examples such as the Toc de Mar bar and the depictions of Montserrat mountain’s rock formations by the Brunells pastry brand.

What gives here is the fact that everyone puts their taste threshold at a different level, and maybe that is why you get the feeling that some selections have been included just to be criticised, as they are either naff, old or simply annoying. It is hard to understand, for example, why the Hotel Camper or the Casa Planells by Josep M. Jujol sit side-by-side with the Arenas shopping centre, the Drummer Boy sculpture and the barracks at El Bruc. Or why the Eixample neighbourhood should be considered the kitschiest neighbourhood of all because it is “a democracy that is fed up with noise and pollution”. In more than one case, the lack of context means that banal and gratuitous selections that should not be there are indeed there.

This elitist sense of irony is also a typical Barcelonan attitude. It makes me think that the kitschiest thing one can do is to write a book on Barcelona kitsch. A kitsch anthology of kitsch for commercial purposes, intended to attract the tourists that we can still just about put up with, the ones that are able to distance themselves from the phenomenon and laugh at it. The hoteliers will be over the moon.