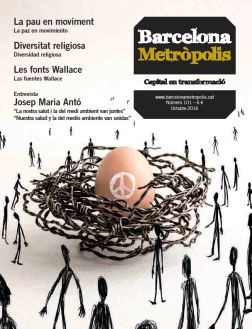

The city has demonstrated that it lives by the value of peace very strongly and that it wants to preserve it. But there are still some clouds obscuring this view that will need to be removed over the coming months, aside from any future challenges we may face.

Human mosaic to form the “Stop the War” symbol, part of the campaign against the American and British troops’ invasion of Iraq; Plaça de Catalunya, 10 April 2003.

Photo: Pere Virgili

At a time when armed conflicts continue to rage, when military spending has reached a scale that is beyond reason, when armies are being privatised, when war tactics are digitalised and the trivialisation of death even reaches children’s games, we must ask ourselves if we, the public, are capable of reacting to these situations. This is obviously no paradise, but it is still worth taking a look at some examples of what has happened historically in Barcelona in this area, focusing on the past 30 years.

The mobilisation of reservists to go to fight in Morocco, in July 1909 following the start of the Melilla War on the 9th of the same month. This sparked the Setmana Tràgica [Catalonia’s ‘Tragic Week’]. Above, troops set sail for Melilla from the port of Barcelona.

Photo: Frederic Balell / AFB

Participants in the Marxa de la Llibertat (‘Freedom March’), a generic name for a series of non-violent marches that took place along roads across Catalonia in the summer of 1976, calling for a statute of autonomy, political freedoms and political amnesty. This led to the creation of the Barcelona’s Casal de Pau [‘Peace Centre’], where a great many pacifist activities were organised during the 1980s.

Foto: Robert Ramos

From the 1980s onwards, Barcelona experienced a surge in pacifism that is still in full force today. The organised groups we have mentioned play a part, as does the disagreement with a series of wars. There is also the debate about Spain entering and then remaining in NATO, the struggles and actions against military service, the non-acceptance of the financial scale of militarism and the emergence of various expressions of the culture of peace.

Furthermore, one could say that this broad pacifist vision, in the case of Barcelona, has been complemented by a positive understanding of peace, that is, defining it not only as the absence of war, but also as the bringing together of different elements that aim to do away with any aspect of structural violence. According to this notion, peace must include social justice, human development, respect for human rights, care for the victims of conflicts and concern for the planet’s survival. Let’s now look at the extensive public repertoire of movements, actions, think tanks, publications, etc. that have been working in this direction for many years, as well as some reservations that arise in this sense.

The anti-NATO campaign

Demonstration organised by the Catalan Anti-Nuclear Committee in La Rambla de Catalunya, in March 1979.

Photo: Pérez de Rozas / AFB

El Casal de la Pau (The House of Peace) in Barcelona was at the core of a significant part of the pacifist activities held in the 1980s. It was created in 1976 after the non-violent (and officially banned) initiative known as the Marxa de la Llibertat (Freedom March) took place along various roads in Catalonia. Pax Christi, Els Amics de l’Arca, the conscientious objectors and members of the Comitè Antinuclear de Catalunya (Anti-nuclear Committee of Catalonia) all shared a space at the Casal. One of the groups of conscientious objectors, the Grup Antimilitarista de Barcelona (Barcelona Anti-military Group – GAMBA), was the first to take anti-NATO action in 1981. From 1983, it helped to set up the Coordinadora pel Desarmament i la Desnuclearització Totals (Coordinating Committee for Total Disarmament and Denuclearisation – CDDT), from which the Coordinadora de Catalunya d’Organitzacions Pacifistes (Catalan Pacifist Organisation Coordinating Committee – CCOP) would emerge a year later, that would be the major force behind the “no” campaign in the referendum to leave NATO in 1986.

The first Jornades Catalanes de la Dona [Catalan Workshops for Women], held in the main hall of the University of Barcelona in May 1976, a founding moment for the Catalan feminist movement.

Photo: Pilar Aymerich

The “yes” campaign for the NATO referendum could serve as a case study of information manipulation and a lack of democratic clarity, as it turned the consultation into a vote of confidence in Prime Minister Felipe González, who had made a U-turn on his initial proposal to leave and proposed to stay, under three conditions that have never been met. Despite the fact that the “no” camp won in Catalonia, the Basque Country and the Canary Islands, the result obviously affected the anti-Nato movement, which had to reorient itself towards other objectives. Initially, this took the form of actions for the dismantling of the US air bases and some demonstrations in Barcelona against US attacks in Libya and US intervention in Nicaragua.

Meanwhile, another factor that had emerged some years before was gaining strength in parallel to the anti-NATO campaign: the conscientious objection to military service. The way it was managed underwent a radical change when the national government approved the draft law regulating conscientious objection and alternative community service, which received parliamentary approval on 28 December 1984. Due to its closed and repressive nature, this law was for the most part rejected by Catalan pacifists and, even while it was still making its way through parliament, it triggered actions of a different kind, such as the protest held at Montjuïc castle in Barcelona on 9 April 1984. That October, the Mili-KK Coordinating Committee was created in Barcelona, carrying out different actions against Armed Forces Week and the abuses that were taking place during military service, as well as work to denounce the situations found in the barracks.

The issue of conscientious objection was complemented with the creation of the Assemblea d’Objecció Fiscal (Tax Resistance Assembly) in Barcelona in 1983, which, by partially disobeying the law on personal income tax, sought to denounce ridiculous levels of military spending and arms investments that arose from Spain joining NATO. Later, given the impossibility of accepting the law regulating conscientious objection and alternative community service, the movement to refuse to do military service gained strength from 1987, creating a key source of pressure that culminated on 9 March 2001 with the abolishment of compulsory military service.

Education for peace

At the same time, an internal thought process was spreading throughout Barcelona that led to intense educational, research and publishing work that generally came under the umbrella of education for peace. On that note, it is worth highlighting the almost simultaneous rise (1983–1984) of the Fundació per la Pau (Foundation for Peace), the Seminari Permanent d’Educadors i Educadores per la Pau (Permanent Seminar of Educators for Peace) at the University of Barcelona’s teacher training faculty, the Secció d’Estudis sobre Pau i Conflictes (Peace and Conflict Studies Section) of the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB) and the Universitat Internacional de la Pau (International Peace University), based at Sant Cugat del Vallès, in addition to the educational work of Justícia i Pau. In the field of peace culture, we should also mention the various periodicals that were pacifist in nature, or simply critical of militarism, and that appeared during this period, almost always published in Barcelona, as well as the newsletters of the aforementioned organisations: La Puça i el General, Mientras Tanto, Pissarra Pacifista, El Viejo Topo, BIEN – Boletín de Información sobre Energía Nuclear (Nuclear Energy Information Bulletin), En Peu de Pau, Per la Pau and Sobre Pau.

This overview cannot ignore the important role of feminism in the struggle for peace, as it developed in Barcelona. The II Jornades Catalanes de la Dona (2nd Catalan Women’s Conference) in May 1982 led to the formation of Dones Antimilitaristes (Anti-Military Women – DOAN), which broadened the struggle for peace to include the refusal to bear children for war or to maintain military spending instead of social spending. Later, there were actions against the inclusion of women in the army and demonstrations and actions outside the Pegaso factory in Barcelona, which produced war material.

The wars of the 1990s

The next phase to consider, now going into the 1990s, largely consists of actions against the many wars of that decade. It began in response to the first conflict in Iraq. Spain’s contribution, providing logistical support and making territory available to the allies, resulted in demonstrations between July 1990 and February 1991. There were also two cases of desertion that took place in Catalonia, featuring two crew members of corvettes headed for the Persian Gulf. There was also the publication of eight editions of the Diari de la Pau (Peace News) newspaper between January and April 1991, which made it possible to present a considerably different view from what was being shown by the major local media, which was very much towing the government line.

The later war in the former Yugoslavia led to the emergence of actions of solidarity with the victims. In 1995, Barcelona City Council established Districte XI (adding Sarajevo to the city’s 10 districts) and, in February 1996, a Barcelonan Local Democracy Embassy was opened in the Bosnian capital, under the umbrella of the Council of Europe. The embassy channelled aid from Catalonia and organised the redevelopment of 1,647 flats. The district was in operation until 2004.

Further anti-war action took place on 15 February 2003 to oppose the imminent attack on Iraq, perhaps representing the watershed in anti-war sentiment in Barcelona and, by extension, all of Catalonia. In fact, on seeing that more than one million people had attended, US president George Bush stated that the Barcelona protest could not stop the war. Pots and pans banging and scores of other protest actions set up by the highly pro-active “Aturem la guerra” (Let’s stop war) platform continued in the city during the months of February and March 2003.

The public presence of Catalan pacifism may not have been so notable in recent years, but that does not mean there has been no action. Several things show us that Barcelona is a wonderful reflection of a wide variety of anti-war concerns and a desire to further the cause of peace. Let’s look at just a few of them.

The non-violent tradition continues in the work of Artesans de la Pau (Artisans of Peace), who, every Thursday since 1981, stand silently for 30 minutes in Plaça de Sant Jaume in front of the Catalan government offices, as an ongoing protest against the armed conflicts that are raging at any given time. Along similar lines, a good number of Catalans have been involved in the Peace Brigades International (PBI) to defend victims of violence in situ, as well as anyone who works to defend human rights.

Education for peace is equally present in the Escola de Cultura de Pau (School for a Culture of Peace) at the Autonomous University of Barcelona; in the annual celebration of Non-violence and Peace Day in schools, which is usually marked in the Poblenou district of Barcelona, around the bronze statue of Gandhi sculpted by Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, winner of the 1980 Nobel Peace Prize; as well as in the works of the Fundació per la Pau, which in 1999 promoted the campaign “Per la pau: no a la investigació militar” (“For peace: no to military research”), which was started in collaboration with the abovementioned Escola de Cultura de Pau, Justícia i Pau and other entities, such as the UNESCO Centre and the United Nations Association.

Another aspect worth mentioning are the annual awards that recognise people and institutions that work in this field. These include the awards created by the United Nations Association, the Alfons Comín Foundation, the International Catalan Institute for Peace (ICIP) and the Víctor Seix Polemology Institute, established in 1967 and now nearing its 50th birthday.

One of the most significant actions for peace that has emerged over the past three decades was the hosting of the Parliament of the World’s Religions, held as part of the Universal Forum of Cultures in Barcelona in 2004. Campaigns such as those for denuclearised cities, against anti-personnel mines and to eradicate cluster bombs are other initiatives that should not be ignored. But we must also remember the ongoing actions that have been carried out for many years to show solidarity with the victims of oppression and war, from which charitable committees and associations have often emerged, such as Stop Mare Mortum, which, complementing the work of SOS Racisme, takes a deep interest in the fate of refugees – why not immigrants? – as had already been done back in 1978 when the Associació Catalana de Solidaritat i Ajuda als Refugiats (Catalan Solidarity and Refugee Aid Association – ACSAR) was created, on the arrival of so many exiles fleeing the dictatorships of Latin America.

Studies on armament

The topic of armament has also warranted special attention. In addition to the longstanding work by the UNESCO chair at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, since 1987 there has also been the Campanya Contra el Comerç d’Armes (Campaign Against the Arms Trade – C3A), initially promoted by Justícia i Pau and the Fundació per la Pau, and later transformed into the Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau. The centre, which is currently an independent institution, is dedicated to topics around defence economics, denouncing military spending, R&D for war purposes, the arms industry and arms trade. In recent years, it has given special attention to so-called armed banking and to the funding of war materials manufacturing.

Demonstration in support of refugees held on 19 June 2016 under the slogan “Open borders, we want to welcome”.

Photo: Pere Virgili

The extensive work carried out has allowed for the institutionalisation of some of the entities involved in pacifism. Initially, various Catalan federations appeared, from which Lafede.cat – Organitzacions per a la Justícia Global (Organisations for Global Justice) later emerged. In addition, the Catalan Parliament’s passing of the Law to Promote Peace in 2003 led to the Consell Català de Foment de la Pau (Catalan Council to Promote Peace) and the International Catalan Institute for Peace (ICIP), which carries out research, promotes peace, produces publications and does archiving. In parallel to this, in 2009 Barcelona City Council created the Centre de Recerca Internacional per a la Pau de Barcelona (Barcelona International Peace Research Centre – CRIPB) as a training centre for crisis management and peace operations around the world.

The city has demonstrated that it strongly lives by the value of peace and wants to preserve it. We can find satisfaction in that, but not completely. Aside from any challenges that may arise in future, there are still some clouds that will need to be cleared away in the coming months. One example is the strengthening of various companies that produce military technology components and are based in Barcelona’s 22@ district, the contradictory and persistent presence of the armed forces at the Children and Education fair, the periodic visits to the city by warships and the military exercises that are still frequent in the hills of Collserola. These things do not allow us to state definitively that Barcelona is “living in the spirit of peace”.

Bibliographical note

1. This and other information appearing in the article are taken from Enric Prat’s book Moviéndose por la paz (Moving for peace), Hacer Editorial, Barcelona, 2006. It is an exhaustive and well-documented study on the peace movement in Spain in the 1980s and 1990s. Another good reference is Xavier Garí’s work Els primers col·lectius i organitzacions per la pau i la no violència sorgits a Catalunya (The first groups and organisations for peace and non-violence in Catalonia), Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, 2002 (master’s dissertation).