The campaign of refusal of military service and substitute social service is one of the greatest struggles of civil disobedience and direct confrontation with the State – as well as its armed branch, the Army – and one of the most representative of recent times.

On 11 and 12 June 1977, around a hundred people marched towards Figueres castle in solidarity with eleven objectors who were imprisoned there, following the first official pardon and the first law regulating objection to military service. This was instigated by Adolfo Suárez’s government, but was rejected by the Conscientious Objection Movement. This picture shows the march as it was intercepted by the Guardia Civil.

Photo: Robert Ramos

From the late 1980s to the suspension of compulsory military service on 31 December 2001, 50,000 young people declared their refusal of military service by disobeying conscription to military or civil service. “Let our lives not be taken from us”, they proclaimed. Many were tried in the courts and nearly a thousand people in Spain were imprisoned. This led to numerous protests, various acts of non-violent struggle, growing social rejection and international support. It was a rebellious gesture – a personal decision within the framework of a collective strategy and wholehearted acceptance of the consequences of this disobedience – that profoundly changed the lives of thousands of people and that, in Spain, has helped to further understanding of the anti-war movement. Undoubtedly, it is symptomatic of the wording of the preamble of the draft Catalan Statute of Autonomy (1931): “The wish of the Catalan people, not as an exclusive aspiration but rather as a redemption for all the peoples of Spain, is for young people to be freed from the slavery of military service.”

Refusal of military service cannot be explained without taking a number of historical considerations into account. First of all, the fight of the first conscientious objectors – a history of dissidence, resistance and influence – laid the groundwork. In addition, Spain’s anti-NATO campaign (1986 referendum) achieved a very sizeable social mobilisation and opened up the debate on taboos left over from the Franco dictatorship. The pacifist movement ignited a powder keg by publicly questioning matters such as the existence and roles of the armed forces; the origin and interests of military conflicts; the concepts of defence, security and enemies; military spending; and the arms trade. Meanwhile, the media started to spread awareness of life in the barracks and the hazing – humiliation and harassment – suffered by drafted soldiers and to release data on the numbers of suicides, accidents and deaths of young people during military service.

A history in four parts

The history of conscientious objection, the anti-militarist struggle and refusal of military service in the Spanish state during the second half of the 20th century is a history in four parts:

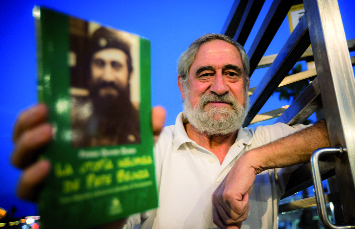

1. Repression (1958-1977). From the first conscientious objectors to the founding of the Conscientious Objection Movement (MOC) in January 1977, the Act of Amnesty and Order of Delayed Entry or Temporary Licence for Conscientious Objectors, whose numbers were increasing. In 1971, Pepe Beunza declared himself a conscientious objector to military service. He was the first person to do so for political reasons.

Pepe Beunza, who in 1971 was the first Spanish conscientious objector for anti-military and pacifistic reasons, pictured in a current photo with the book La utopía insumisa de Pepe Beunza [The defiant utopia of Pepe Beunza], in which historian Perico Oliver recounts his epic experience.

Photo: Robert Ramos

3. Towards refusal of military service (1985-1989). From the declaration of collective objection against the LOC – more than 2,000 conscientious objectors submitted a document expressing their firm resolve to disobey this act – to the first appearance before the military courts of objectors who had refused military service. On 20 February 1989, 57 young people throughout the Spanish state – eight from Catalonia – asserted their status as civil citizens by refusing to recognise military authority and expressed their decision not to do military service. From that day forward, every two months – coinciding with a new draft – more young people appeared before military judges to declare their refusal of military service.

4. Justifiable refusal of military service (1989-2001). From the first appearance of military service refusers to the suspension of compulsory military service in the Spanish state. The various Spanish governments used the same fruitless strategies: divide, dilute, assimilate, distort, criminalise and repress. When repression became increasingly unjustifiable, when public support increased, that was when the Spanish Government – and the military – were forced to backtrack on the measures they had implemented to stop the boomerang effect. They also had to amend legislation in order to stanch the constant spending and repair the reputation of the Spanish army. It must be borne in mind, however, that the suspension of compulsory military service could be legally revoked by cancelling the current organic law, since Article 30, Paragraph 2, of the (unamended) Spanish constitution states: “The law shall determine the military obligations of Spaniards and shall regulate, with the requisite guarantees, conscientious objection and other grounds for exemption from military service; it may impose, where appropriate, substitute social service.”

Networking and involvement in other movements

The refusal of military service campaign was organised and operated as an assembly, was coordinated on a state-wide scale and brought together various organisations. In Catalonia, it was promoted by the Conscientious Objection Movement, the MILI-KK coordinator, the Anti-Militarist Group for the Refusal of Military Service (CAMPI) and the numerous local anti-militarist assemblies. The movement was not limited to urban settings; on the contrary, its activity spread throughout Spain and led to the widespread founding of working and support groups. Furthermore, networking and the establishment of close involvement with other social movements – feminist, student, neighbour, gay and lesbian, pro-independence, environmentalist, libertarian, labour union, squatter and leftist anti-capitalist parties – was important for the exchange of ideologies and actions.

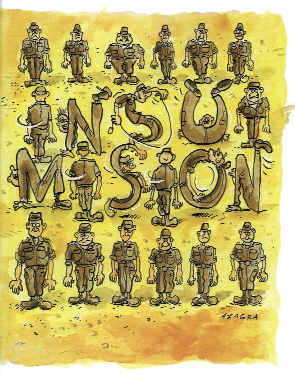

Illustration by the artist Azagra for the book Seriosament… 25 arguments per la pau en còmic [Seriously… 25 reasons for peace in a comic], by the Foundation for Peace.

In addition, many people linked to the cultural sphere were directly involved: cartoonists, illustrators and painters (Cesc, Fina Rifà, Nazario, Mariona Millà, Azagra, Carme Solé, Ivà, Perich, Pilarín Bayés, Fer, etc.); singers and musical groups (Lluís Llach, Companyia Elèctrica Dharma, Maria del Mar Bonet, El Último de la Fila, Marina Rossell, Lluís Gavaldà, Gerard Quintana, Brams, etc.); writers (Teresa Pàmies, Miquel Martí i Pol, Maria-Mercè Marçal, Julià de Jòdar, Anna Murià, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Montserrat Roig, Paco Candel, Maruja Torres, etc.); and actors and various people from the world of theatre and cinema (Sílvia Munt, Pep Munné, Ariadna Gil, Guillem-Jordi Graells, Ventura Pons, Comediants, etc.), to name but a few. Lluís María Xirinacs, Arcadi Oliveres and Gabriela Serra deserve special mention for their teaching.

In all likelihood, the main legacy, the most significant educational experience that lies in the refusal of military service, is having been able to confirm civil disobedience’s enormous potential as a tool for individual and collective change and its enormous capacity for social and political transformation. So long live the rebellious gesture.