In our city, the work for peace must be translated into policies aimed at reducing the levels of direct, structural and cultural violence. To design such policies, it is necessary to count on the know-how that comes from the experience of women.

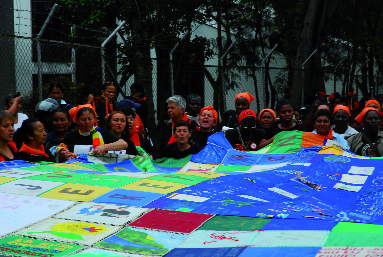

Demonstration by Madres de la Plaza de Mayo [Mothers of Plaza de Mayo] on 24 March 2013, the anniversary of the coup d’état by the Argentinian army.

Photo: Alejandro Pagni / AFP / Getty Images

Since then, feminism has delved much deeper into these connections, establishing the existence of what has been called the continuum of violence. This concept, created by Caroline Moser in 2001, brings up the complexity of the interactions between violence and gender systems that act in our societies in the economic, social, political and symbolic fields, as well as in interpersonal, family and community relationships, at national and international level. In turn, the studies on the construction of masculinity in relation to military values and behaviours indicate that militarism has created a model of hypermasculine hero that is characterised by contempt for anything feminine, the criminalisation of anything different and the devaluation of one’s own and others’ lives.

On a deeper level, feminist research has investigated the foundations of the patriarchal socio-symbolic system that provoke and justify war. In her article “La cólera masculina hacia lo otro” (“Masculine rage towards the other”; 2005), María Milagros Rivera Garretas notes how in patriarchy, the relationship with otherness translates into objectification and insignificance, the ingredients of dehumanisation that are needed to form an image of an enemy that can be attacked and killed without a guilty conscience. Ecofeminism has also shown the way patriarchy has trivialised nature and bodies by considering them inexhaustible resources that can be exploited and subjected to violence without any cost. Women, who are the quintessential other in relation to men, know male rage well and their contempt for bodies in contexts of armed violence as well as in times of peace.

A concept that has helped to understand, and to condemn, the mechanisms of patriarchal domination has been gender defined as a social construction built on the difference between sexes translated into inequality. The gender system ensures that relationships in which men dominate women are reproduced by means of the repetition of roles, behaviours and imagery that establish and confirm what it is to be a woman and what it is to be a man, without leaving any room for the free meaning of the fact of having been born with a body sexed as feminine or masculine. Gender, where it intersects with class, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age or other elements of diversity that build otherness with regard to the white, Western male that has been instituted as the single and universal subject, multiplies the effects of discrimination, marginalisation and violence.

Creativity and resistance

However, the capillary action of violence that becomes omnipresent in the above-mentioned continuum and the means that activate violence and reproduce it, encounter resistance in the practices and spaces for relationships that are created more so by women than men, generating and maintaining a logic of care and respect towards human beings.

Anti-nuclear camp at the Royal Air Force base at Greenham Common, England, in December 1987.

Photo: Sahm Doherty / The LIFE Images Collection / Getty Images

There is open resistance that translates into social creativity in the public space, which opens up new symbolic worlds and makes possible that which was seemingly impossible. This was done by the women of the Greenham Common camp, which during the 1980s and for 20 years set disarmed bodies and imaginative action against the deployment of NATO nuclear missiles, until they got the military base to close. We also know that the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo opened the first cracks in the Argentine dictatorship by keeping their children, who repression had tried to eliminate, in the public eye. Closer to home, the wave of conscientious objection to compulsory military service in our country managed to put an end to this service and played a role in undermining the connections between masculinity and militarism.

Women’s practices for peace emerge from relationships and are fed by the mobilising force of emotional bonds. This has been demonstrated to us by the mothers of Soacha who, in searching for their children, exposed Colombia’s counterinsurgency policies in the cases of the so-called “false positives”. In other situations, women create cross-cutting policies by forming bonds between themselves that allow them to cross the dividing lines of conflicts, as the Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot women from the organisation Hands Across the Divide have done.

There are other forms of resistance to violence that have been developed and passed down along countless generations of women. They consist of slowing the advance of violence and its destructive capacity by creating and recreating humanitarian conditions and bonds between people. This resistance that insists on the priority of taking care of bodies and the dignity of children so they can develop and use their abilities, is particularly practised by women in the contexts of war, post-armed conflict and in any situation in which life and coexistence are in danger.

“Between killing and dying there is a third alternative: living”, said Christa Wolf in her work Kassandra. This is the deeply political option explained to us by the experience and practices of women in relation to war.

Our peace

If we have to look for an indicator of building peace from the experience of women, this would not only have to refer to the absence of war, but also the absence of violence, because for women, when the war ends, the violence does not. The motto created by Women in Black Against War (the Catalan division is Dones x Dones), “For a peace that is ours”, calls for a social functioning that disrupts patriarchal domination and militarism, people with the ability to deal with conflicts by transforming them and avoiding violence, and human communities that work for justice by looking after relationships and common life. It calls for “living peace”, going back to Christa Wolf.

In our city, the work for peace must therefore be translated into policies aimed at reducing the levels of direct, structural and cultural violence. To design such policies, it is necessary to count on the know-how that comes from the experience of women. Today, moreover, we have an urgent task: the reception of the forcibly displaced population fleeing the scenes of war in the Middle East. A reception, particularly for women, where we respond to what they lack and need, and at the same time listen to their projects and desires. The reception of displaced women is an opportunity to receive the know-how they bring with them, to allow their skills and initiative to blossom in our country. Creating a favourable atmosphere for bonds to grow between women is a good way of resisting violence, but particularly of activating creativity to bring us closer to more peaceful ways of life.