The new visibility of women and their demands also set out to express itself through cinema, to reflect the political activities of the second wave of feminist groups and be used as propaganda to raise awareness.

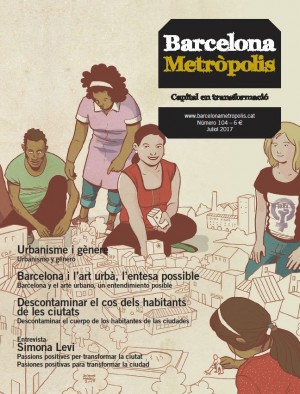

Still from the film Jeanne Dielman, 23, Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, directed by Chantal Akerman (1975).

Ever since the invention of cinematographic devices, the images of possible cities have multiplied: gathering the testimony of the flâneur – that historical figure turned literary emblem by Charles Baudelaire – the filmmaker, like the photographer, became the vagabond wandering the city, capturing it in his lens. The flâneur, that child of modernity, idly meandering the streets, an avid spectator of the urban context and the life that passes through it, became an artist by turning his experiences into language. His predisposition to contemplating the city, and his spatiotemporal mobility within it, finds its heir in the filmmaker, a snoop able to use his words to recreate and shape time and space themselves. The city is the subject of some of the very earliest pieces of film, such as the documentary short Milan, Place du Dôme, by the Lumière brothers (1896); the material for formal experimentation in titles such as Berlin: Symphony of a Great City by Walter Ruttmann (1927); and a dystopian backdrop for describing the miseries of the society that designed it, like in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) or The Crowd by King Vidor (1928); and, later, the image of wartime destruction in the Italian neorealism movement.

The act of immersing oneself in the crowd, or crossing the borders of one’s private space to gain entry into the public area of flânerie, as defined in the 19th century, is one that is reserved for men, just as entertaining observation is reserved for the bourgeoisie. Without any equivalent for a woman in that social class, prostitutes are the closest we get to this figure who wanders through the urban fabric, even though for them it constitutes an exhibition space for offering their wares. Women’s occupation of the public space has long been associated with the sex trade, as reflected in the term saying “streetwalking”.[1] Although industrialisation has been responsible for the gradual separation between the public and private space in Europe since the 18th century, its development required women to pass through the public space: during the second half of the 19th century, in highly industrialised cities such as London, large numbers of women were employed in factories as labourers, while at the end of the century it turned women of the Parisian bourgeoisie into consumers who frequented the first department stores that lined the streets.

Taking the streets became a tool for the first feminist women’s movements, which, by merely making themselves present, by putting themselves in the political space, were looking for a new position in society. The suffragette movement and the second wave of feminism took place in the public space in order to resist being banished to the domestic space, in an effort to open up new possibilities. Simply being out on the street became an act of self-liberation.

The new visibility of these bodies and their demands also set out to express itself through cinema, reflecting the political activities of the second-wave feminist groups and being used as propaganda to raise feminist awareness or to serve as a means of self-expression or a place to project new images of women. Moreover, the questioning and transfiguration of cinematographic language in formalistic pieces, set out to reveal the ideological codes of representation.

Domestic captivity

The film Jeanne Dielman, 23, Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, directed by Chantal Akerman (1975) reveals how women are imprisoned through the ideology of the home, which limits them to care-giving and reproductive tasks. And it is demonstrated through the protagonist: a middle-aged, working-class Belgian widow, captive in this domestic space where, although she no longer has a husband, patriarchy persists. Forgetting herself in order to care for others — her son, the men who give her money in return for sex — the rejection of desire or the impossibility of expressing herself constitute the walls by which she is confined. The camera’s emphasis on this apartment, filmed from different angles and with long, fixed shots, underscores the unvarying existence of the protagonist and delimits the space in which the saying “the personal is political” is so valid. Trapped in the repetition of a routine that amounts to unpaid labour, Jeanne ends up challenging the established order with her own body.

If Akerman’s film shed a light on the labour that keeps the city and the capitalist system running behind closed doors, Helke Sander’s Nr. 1 – Aus Berichten der Wach – und Patrouillendienste (1984) focuses on issues such as the feminisation of poverty and the subsequent problems of getting access to housing. The lead character of this film, burdened with two children and a message of distress, climbs to the top of a crane to demand housing. From up on high, with views out over the city that marginalised her, her message is revealed, and with it the need to build, from this very crane, a new city that meets the needs of women.

Oppression after the revolution

Both films bring into focus women’s experience of the city and reveal the cracks that need to be repaired, as does Lizzie Brodin’s film Born in Flames (1984), although in the latter they implement some of the solutions. Set in a New York of the future, after a failed social democratic revolution, the film reveals the diversity of women’s voices at the intersection with race, class, sexual orientation and their differing needs. The continuation of oppression after the revolution brings the different groups of women together to organise and take to the streets to defend their jobs, combat harassment on the street and work together in care-giving tasks with a view to creating a better balance of paid and domestic work. Mobilising, creating alliances, taking direct action and using communication channels to declare themselves as political subjects are the methods they use to achieve their emancipation.

Feminist cinema has proposed the creation of a new social vision and imagined new subjectivities and living spaces by creating images in which to improvise new types of communities. The city fired the utopian dreams of the suffragettes and feminist activists of conquering a space that was denied them, and the city became somewhere to explore women’s public and private lives through forms of expression such as film, enabling a late flâneuse to take her place behind the camera. Now we must continue to feed our collective fantasies in order to transform the city into a space that is equal and free of sexism; we must rewrite the uses of the city from the perspective of the diverse political subjects who inhabit it.