"We can't have a vocation for what we don't know"

Trained in Pedagogy and specialising in new technologies applied to education, Susana Navarro is the head of educational programmes in the fields of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics) and sustainability at the Barcelona Education Consortium (CEB).

We talked with her about the need for a STEAM approach in the classroom, the cross-cutting nature of this knowledge, vocations in science and technology subjects, and some of the CEB’s collaborations with Barcelona Science and Universities, among other topics.

At the beginning it was STEM. Why the A, for art, has been added to the acronym?

I think that adding the A makes it possible to “sew” the relationship between the different fields. Art can appear in the process as well as in the final result, if it exists at all. For example, in the scientific method we start from questions to arrive at a hypothesis. If we introduce disciplines such as theatre, drawing or plastic arts, we are sure to ask ourselves questions (and give answers) that, rationally, we would not have asked at the outset. It is also a way of bringing the emotional part closer and this allows us to attract students from different backgrounds.

A is also understood as design, for example, of a final product. Digital fabrication is the best example to understand it: we respond to a need by building it from scratch. We start from questions such as “what for?”, “why?”, “for whom?”, “how are we going to do it?”. But we also need to put the aesthetic vision: “what do I want my object to be like?”.

What is the STEAMcat programme?

The STEAMcat programme is a high-intensity programme that accompanies teachers for three years to reflect on innovative methodologies and aims to bring science to the school in a real way. It is a paradigm shift in terms of the teaching staff, which has a direct impact on students.

School curricula already include science and technology subjects. What does a programme like STEAMcat bring to students and teachers?

It brings learning and teaching from a global perspective, which is how the world is structured.

For example, the other day my son was confined at home and was meeting with his classmates to decide how they should build a bionic hand. In one hour he did maths, programming, science, language, sustainability, drawing… and he worked on skills such as teamwork, decision-making, adapting to change, creativity… This is what a programme such as STEAMcat or similar programmes provide: empowering teachers to accompany these processes.

There are already many schools that work in this way, but high-intensity programmes such as STEAMcat can give a boost to the teaching staff, as it is not easy to change paradigms from one day to the next. Training and support are key in this type of project.

Is there a lack of scientific and technological vocations?

I would say that there is a lack of freedom and knowledge to awaken vocations. We are not aware of the cultural heritage we carry with us. It will be very difficult for a girl to think about being an engineer if she has not had any reference during her childhood and, even worse, if she has received negative inputs about her abilities. We cannot have a vocation for what we do not know, so we must bring the scientific community as close as possible to the school and family environment.

Statistics tell us that there is a huge gap between boys and girls who access scientific and technological studies, and forecasts tell us that we will lack many of these profiles in the coming years, so we must work to meet this future demand.

But we should not only focus our actions on university studies, but also on vocational training, which has the same or more demand for these profiles.

How do STEAM programmes contribute to awakening these vocations among girls and women?

The Consortium ensures that the programmes offered through the unified call for applications include this objective. We are looking for ways to prioritise female referents and we are trying to bring the scientific community closer and closer to schools. There are specific programmes that work on scientific vocations, such as Inspira STEAM, Aquí STEAM UPC or 100tífiques. We must allow experts to enter the classroom and students to go to research centres and companies to learn about real practice.

Programmes help, but they are not enough. To support this “stool” we need three main legs: the school, the family and the working environment. We need to create channels to bring these three worlds closer together, with a special focus on the most vulnerable environments. There are not only gender differences, but also differences by territory and family income. At the Consortium we focus on equal opportunities.

Have you detected a growing interest in STEAM subjects among female students in recent years?

Yes, but the results will be seen in the medium to long term. I think girls’ self-concept is starting to change, but there is still a long way to go. In universities, the effect is already being felt to some extent, with an increase in the percentage of girls entering these careers.

We have detected that it is necessary to act especially in the early stages, since girls at the age of 6 already have very internalised stereotypes.

What success stories would you highlight?

It is very difficult to know which actions have a high impact, so we must carry out general studies in the medium to long term, and not so much of a specific programme or activity.

For me, a success story is when a headmistress tells you that thanks to programmes such as citizen science, the number of students (and girls) in the science baccalaureate has increased. A success story is also when a girl tells you, after listening to a scientist, that she had never considered studying science and that the conversation has made her want to do so. A success story is that there are schools that want to make their educational project unique in STEAM. The Rec Comtal, Angeleta Ferrer, Coves d’en Cimany and Mirades schools are some examples.

How are STEAM proposals evolving in schools?

In recent years, the volume of STEAM educational proposals aimed at schools has increased exponentially. From the CEB we saw the need to organise and channel the offer, analyse the needs, make the most of resources and share language and meanings with the different institutions and administrations involved (Universities, Barcelona Activa, Libraries, Manufacturing Athenaeums, CRPs, different areas of the City Council…). For this reason, it was decided to set up a working group with the different agents to build a city map of STEAM proposals, in the form of an itinerary, with the aim of disseminating them in educational centres.

What other actions promoted by the Consortium would you highlight?

It is worth highlighting the Science Congress, a programme in which the students are the main protagonists. You only need to listen to the children on the day of the Congress to know that the programme has an impact. It is very exciting to see how they explain, in their own words, what science is. For the students it is important that what they do has relevance and recognition, and that is why last year we included scientists in the closing ceremony who gave a presentation on their research.

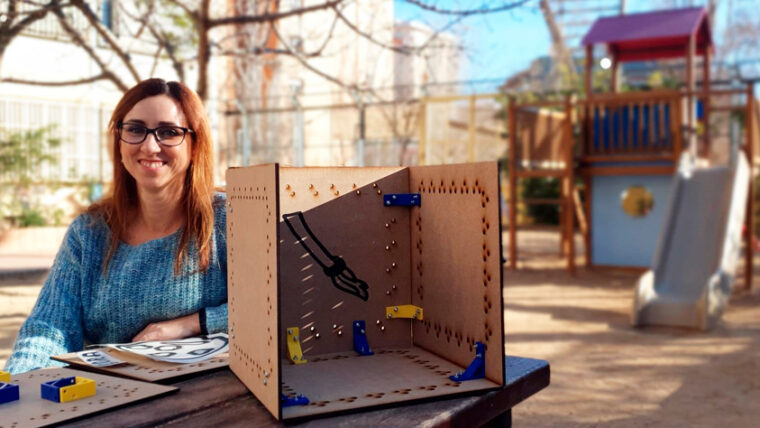

We should also talk about the Digital Fabrication Educational Programme, which for me is the STEAM programme by definition, since it works in a globalised way in almost all subjects. It is important because it is based on a real need that is close to the students, seeking solutions through trial and error and integrating the different areas of knowledge. This allows children to be more motivated, to understand the usefulness of the knowledge acquired and thus promotes meaningful learning.

In addition, opportunities arise where families are involved through the Manufacturing Athenaeums, thus reinforcing the three legs of the stool I mentioned earlier.

What are the Consortium’s collaborations with Barcelona Science and Universities in these areas?

The main initiative is the Citizen Science in Schools programme, but we work together on any action aimed at educational centres. The Barcelona Science Plan is our umbrella and our motto is “going hand in hand”. That’s why we often meet to make the most of initiatives such as the Science Festival, Escolab, Pequeños Talentos Científicos, the City and Science Biennial… They are also part of the STEAM research group. Of all these collaborations, I would like to highlight the day-to-day collaboration between colleagues from the different departments, as there is a very good harmony.

How do you value the experience of Citizen Science in Schools?

There is a before and an after in incorporating citizen science in schools. Four or five years ago, hardly anyone had heard of it. It is a key initiative to bring science closer to citizens because it means being the protagonist of a research project, it means putting faces and breaking stereotypes, it means doing real science (getting into a river to take samples, for example) and this is a very important value to promote. The Citizen Science programme is one of the most popular in the field of research, science and technology, and the centres always want to repeat it.

What about the Escolab programme?

Being able to enter a laboratory or research centre is priceless. We have a very powerful resource in the city, which other places don’t have, and we should make the most of it. When I was a student I never went to visit a facility of this kind, nor did any scientist explain to me what their day-to-day life was like. If someone had done so, perhaps I would have thought about other things. It is vital for students to know first-hand what science is and Escolab makes it easier for us to do so.

How have you experienced the CEB’s participation in major events such as the City and Science Biennial?

The Biennial is a magical moment where things happen that you don’t expect! Citizens have the opportunity to get close to renowned international and local references and we are able to break the routine and say: “listen, science is part of your life. Do you want to know how?

I had the opportunity to see two Nobel Prize winners (Ada Yonath and Jerome Friedman) talking to primary school children. It was a very special moment for all of us who were there. It created a very close and familiar atmosphere of conversation, and I am convinced that there will be many boys and girls who will never forget it.

How can the STEAM approach contribute to meeting today’s educational challenges?

I think the STEAM concept came about precisely to vindicate the need to align the learning that happens in school with what happens outside school, which is happening at a faster pace. The world is not divided into subjects and that is why today’s students learn in a different way, so we must teach in a different way.

Some of today’s students will be doing jobs that do not yet exist, and preparing them for this uncertainty is a big challenge.